This is the multi-page printable view of this section. Click here to print.

Pigsty Blog

- Database

- Scaling Postgres to the next level at OpenAI

- Database Planet Collision: When PG Falls for DuckDB

- Self-Hosting Supabase on PostgreSQL

- MySQL is dead, Long live PostgreSQL!

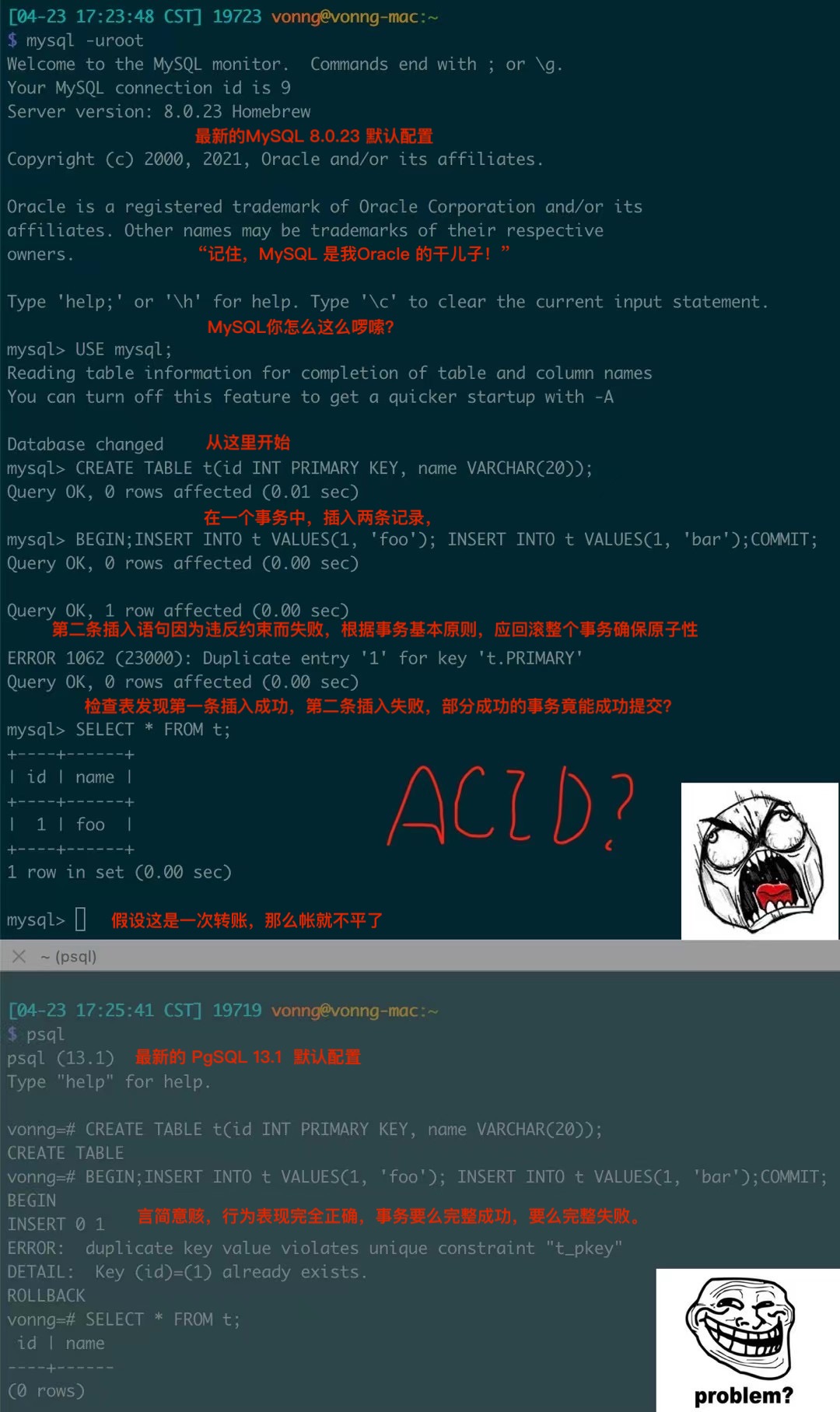

- MySQL's Terrible ACID

- Database in K8S: Pros & Cons

- NewSQL: Distributive Nonsens

- Is running postgres in docker a good idea?

- Cloud Exit

- S3: Elite to Mediocre

- Reclaim Hardware Bonus from the Cloud

- FinOps: Endgame Cloud-Exit

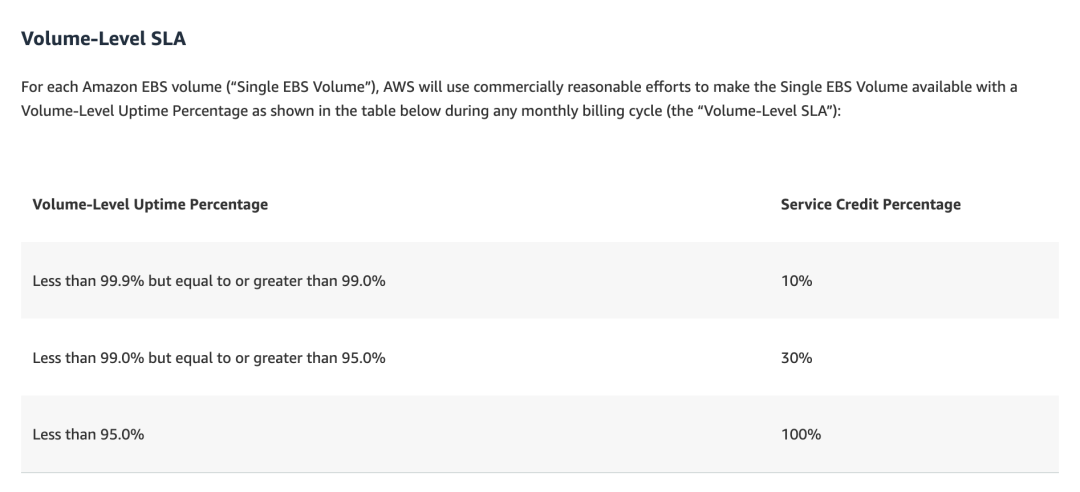

- SLA: Placebo or Insurance?

- EBS: Pig Slaughter Scam

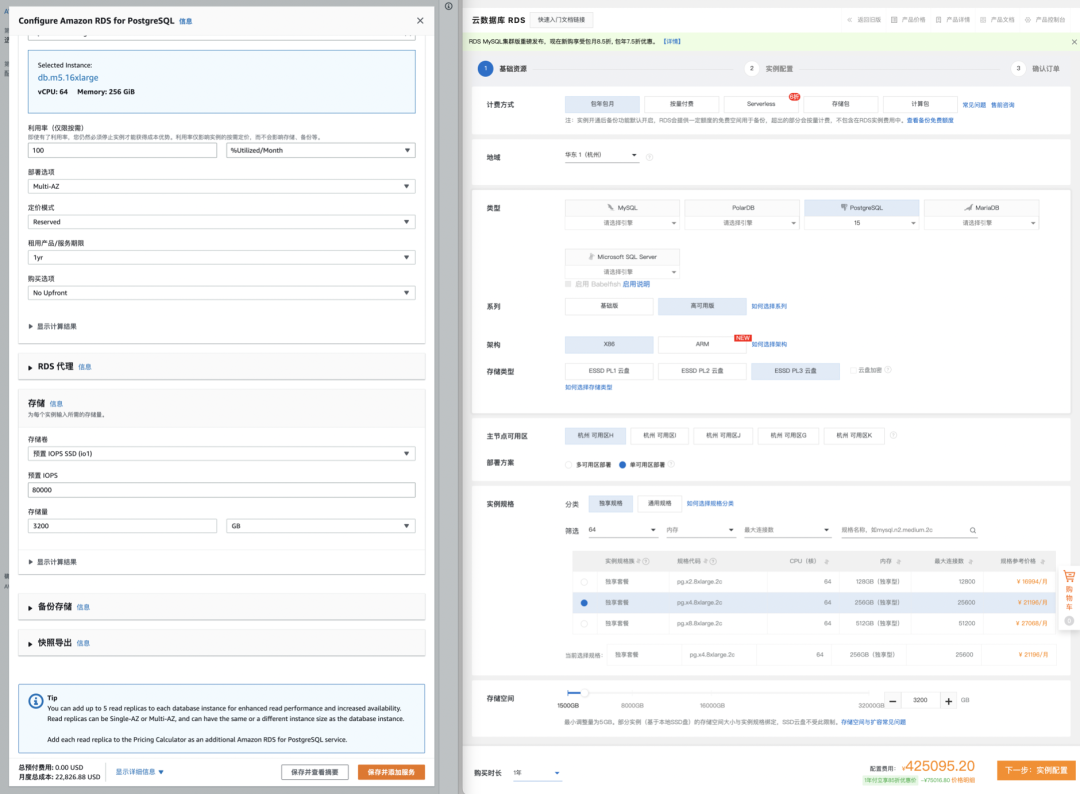

- RDS: The Idiot Tax

- Postgres

- pg_exporter v1.0.0 Released – Next-Level PostgreSQL Observability

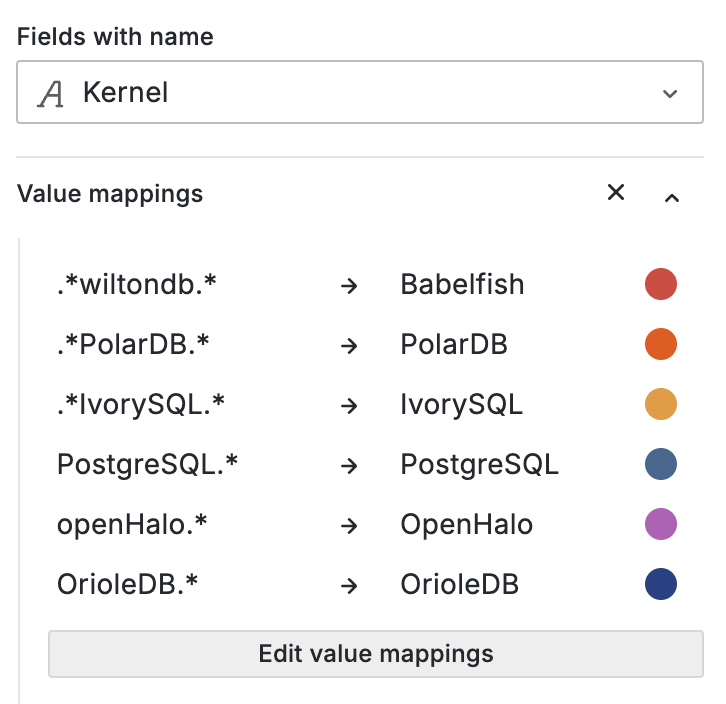

- OrioleDB is Here! 4x Performance, Zero Bloat, Decoupled Storage

- OpenHalo: PostgreSQL Now Speaks MySQL Wire Protocol!

- PGFS: Using PostgreSQL as a File System

- PostgreSQL Frontier

- Pig, The PostgreSQL Extension Wizard

- Don't Update! Rollback Issued on Release Day: PostgreSQL Faces a Major Setback

- PostgreSQL 12 Reaches End-of-Life as PG 17 Takes the Throne

- The idea way to install PostgreSQL Extensions

- PostgreSQL 17 Released: The Database That's Not Just Playing Anymore!

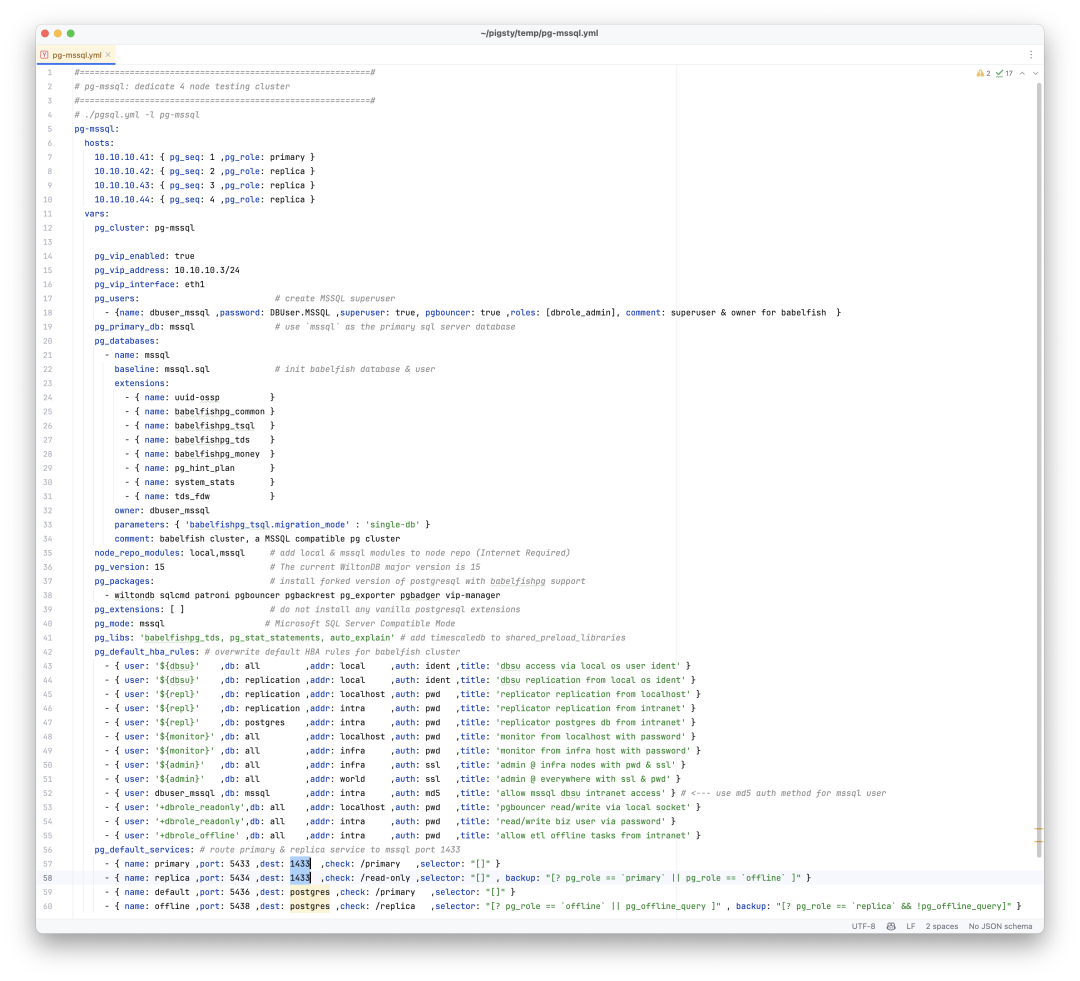

- Can PostgreSQL Replace Microsoft SQL Server?

- Whoever Integrates DuckDB Best Wins the OLAP World

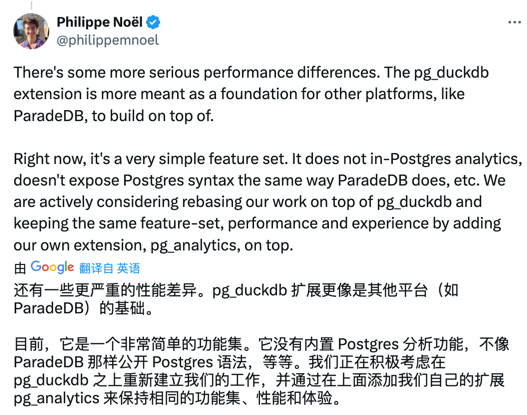

- StackOverflow 2024 Survey: PostgreSQL Is Dominating the Field

- Self-Hosting Dify with PG, PGVector, and Pigsty

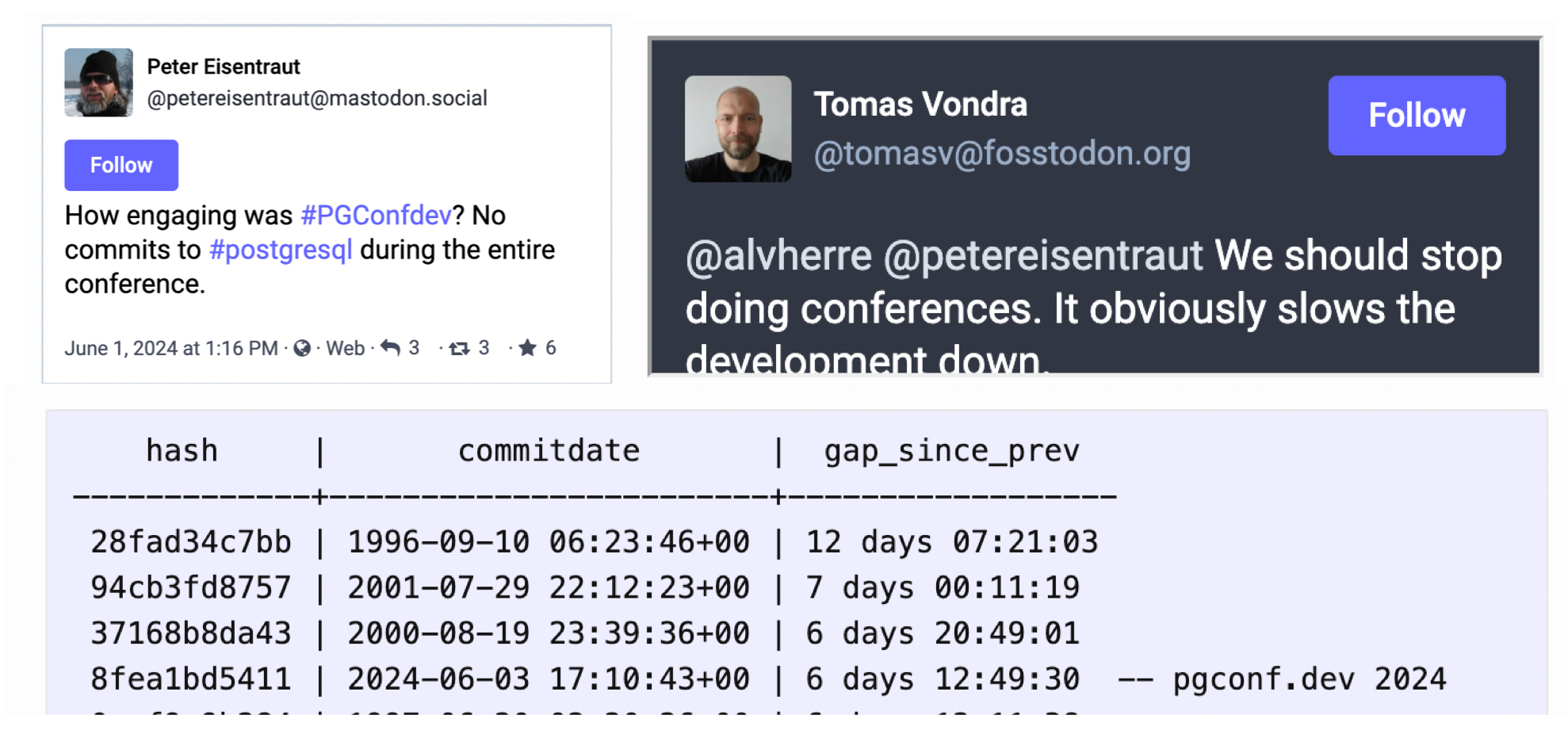

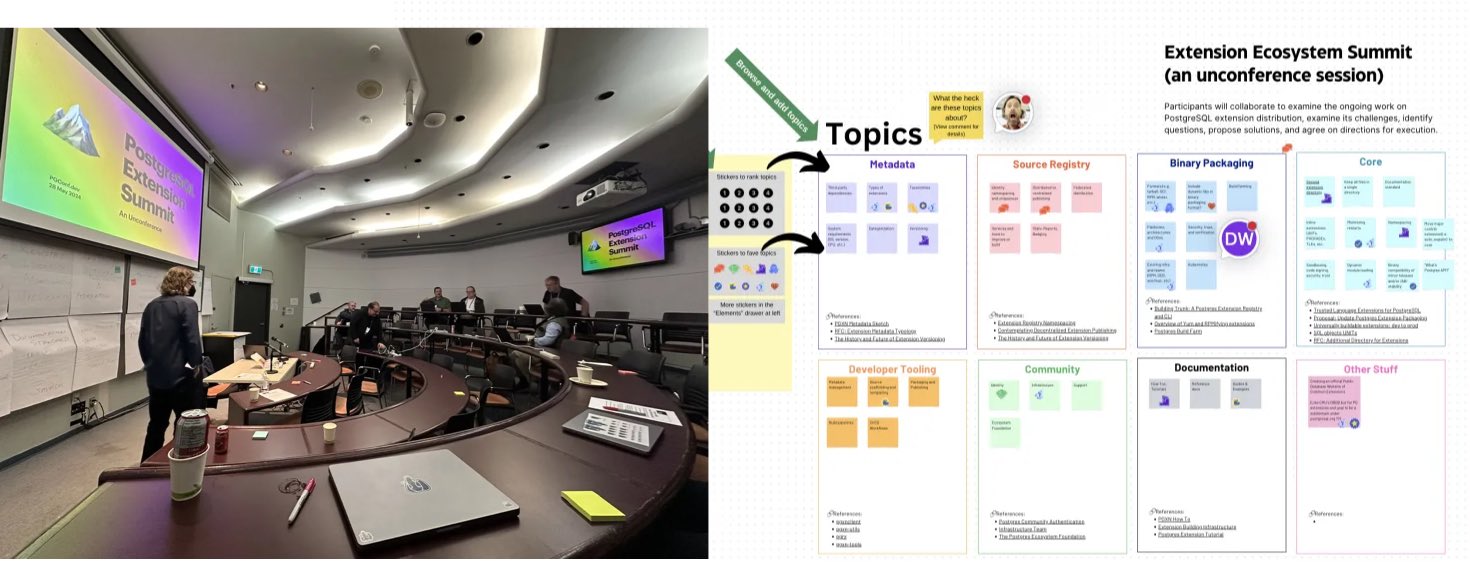

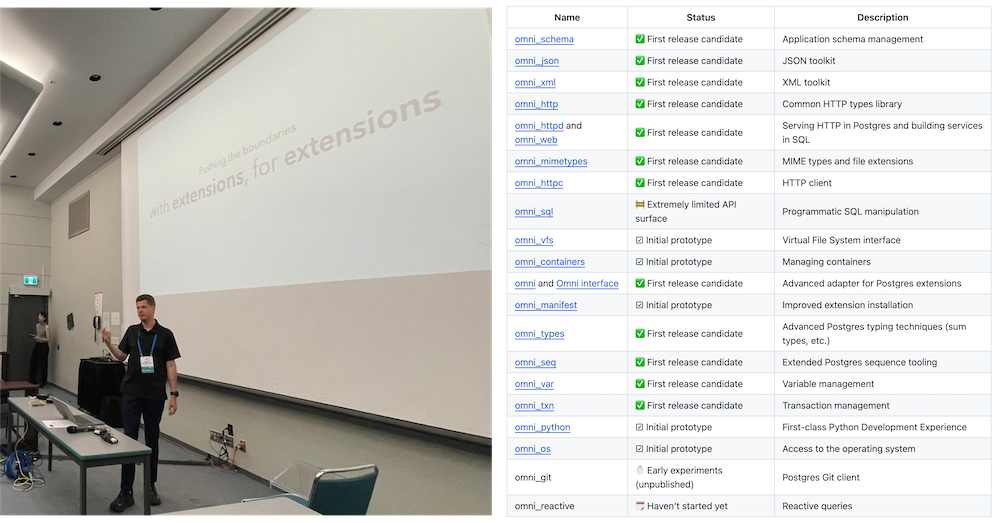

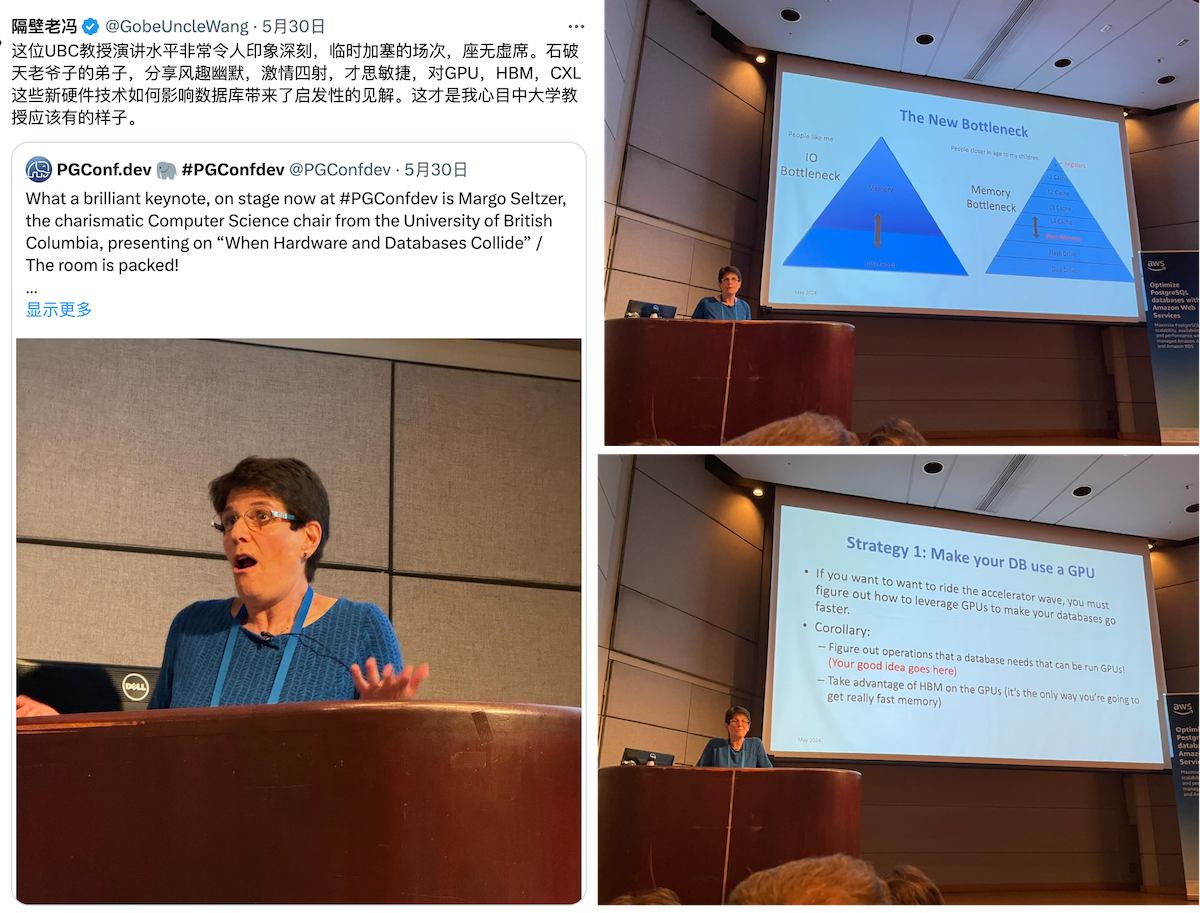

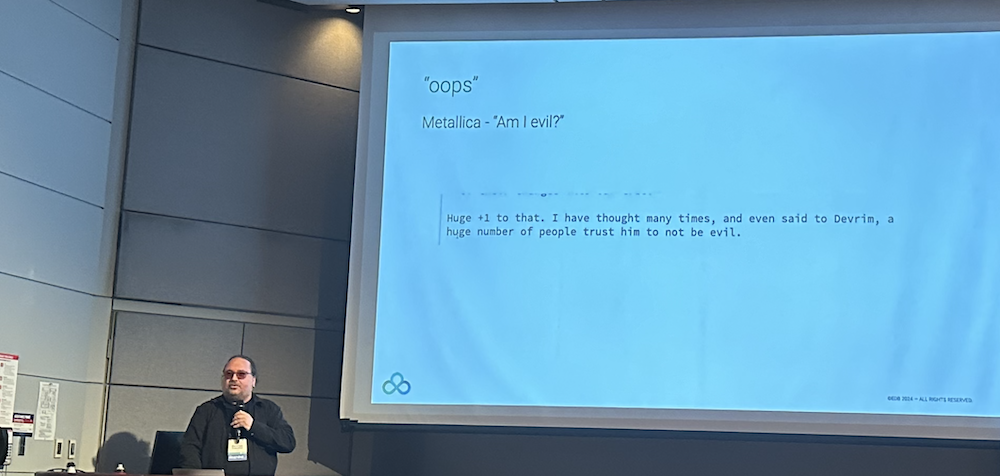

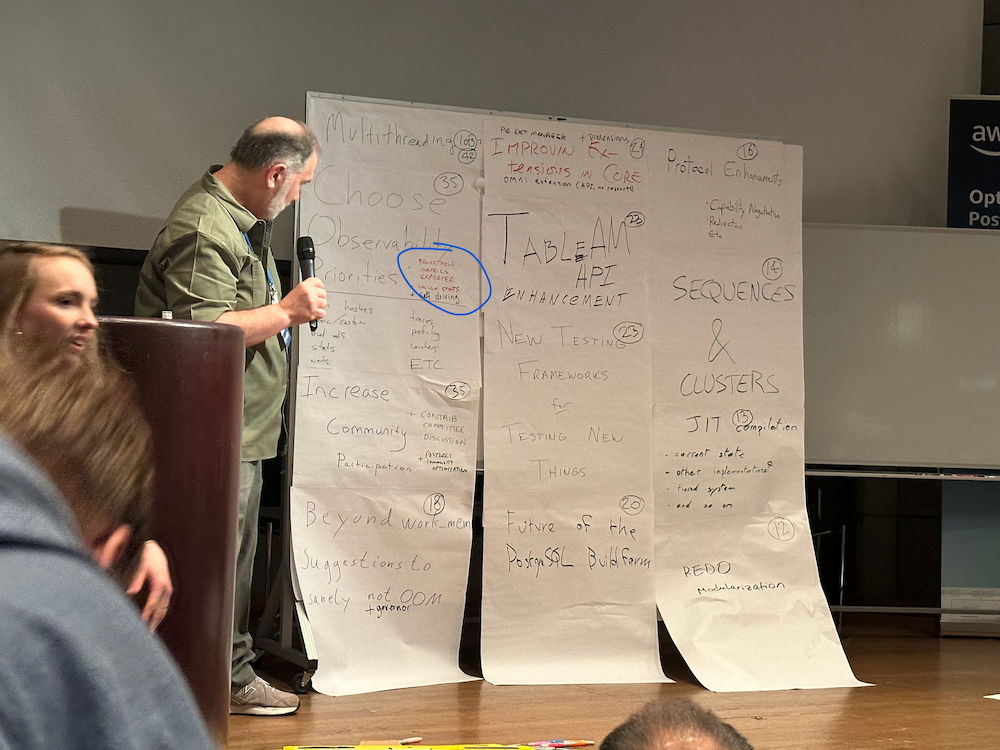

- PGCon.Dev 2024, The conf that shutdown PG for a week

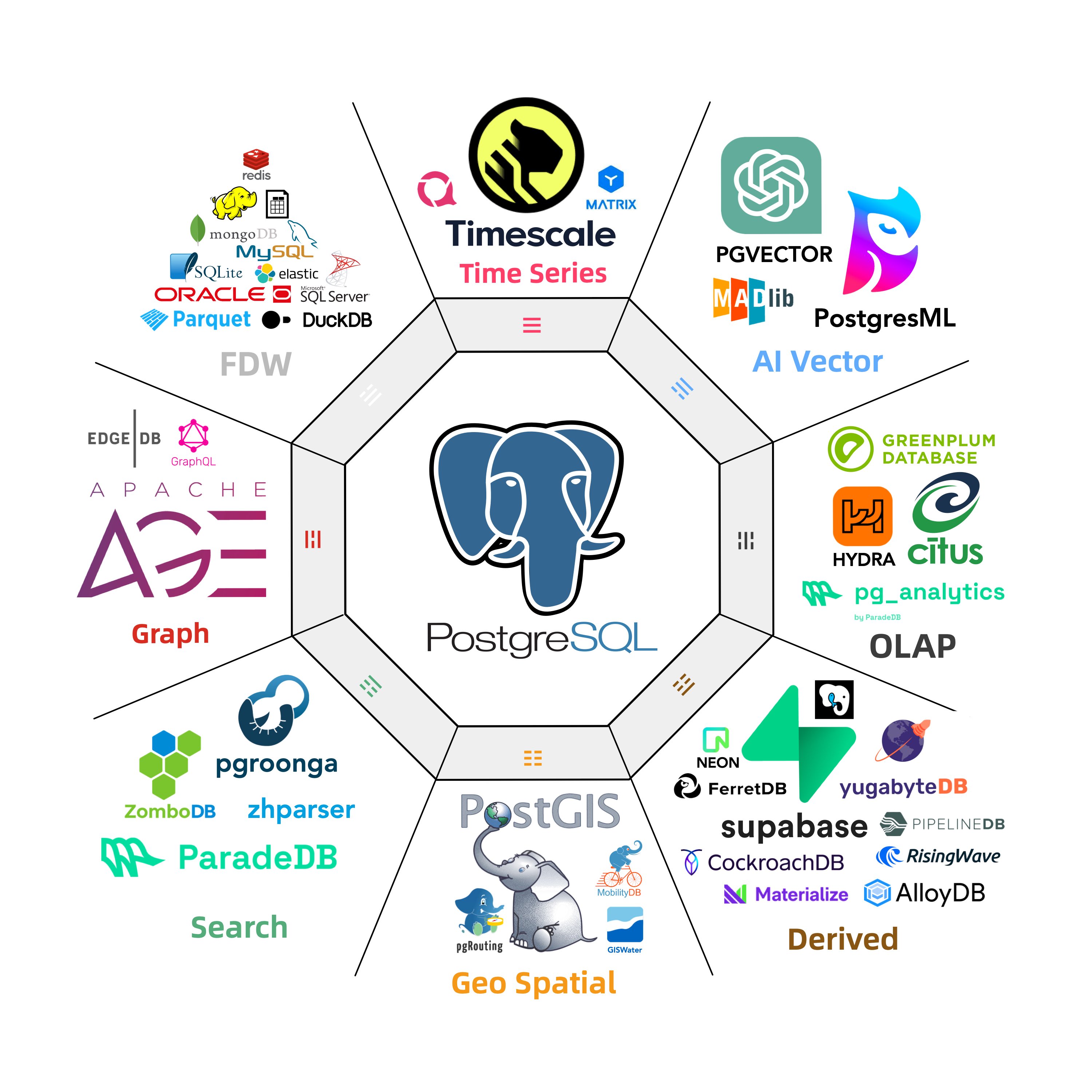

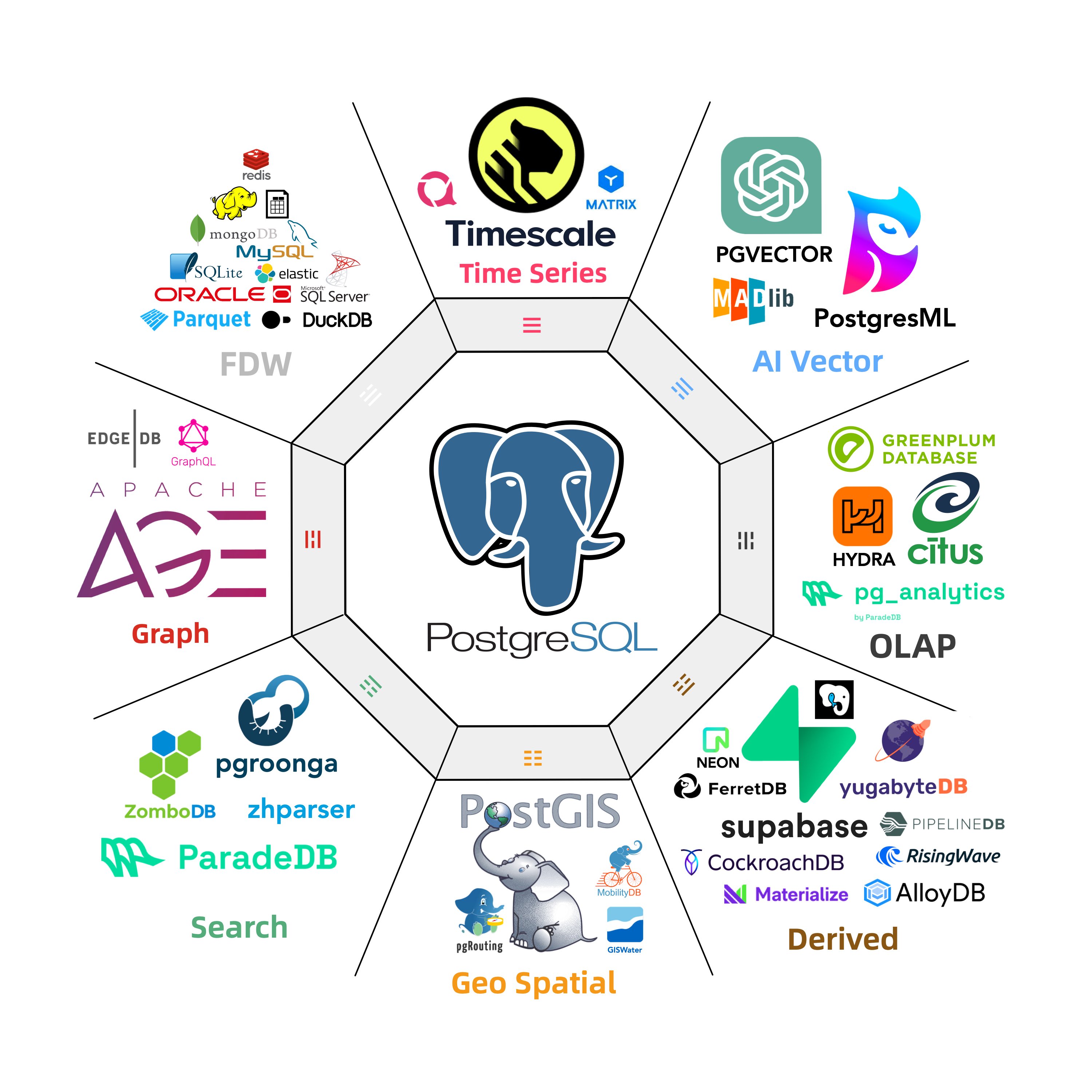

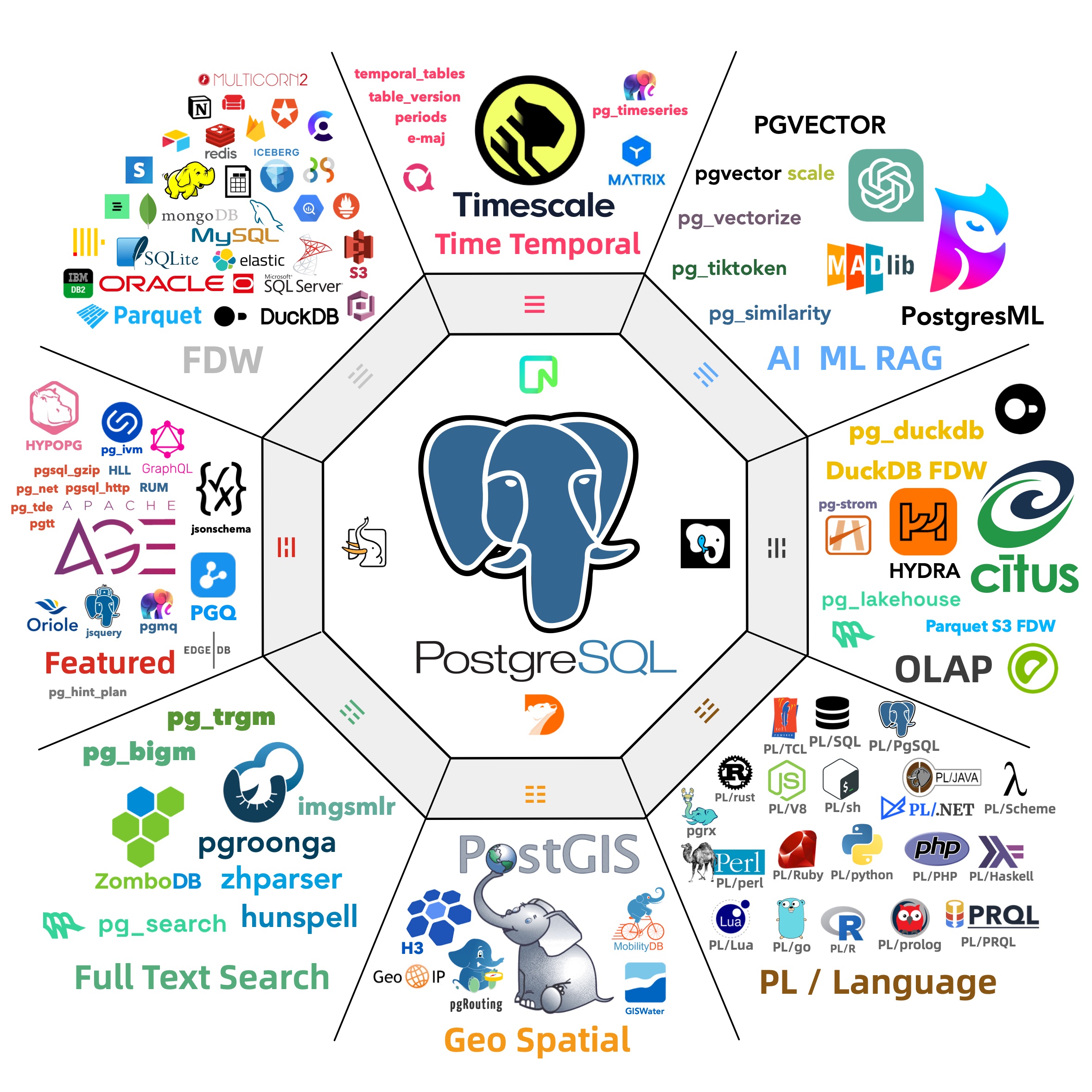

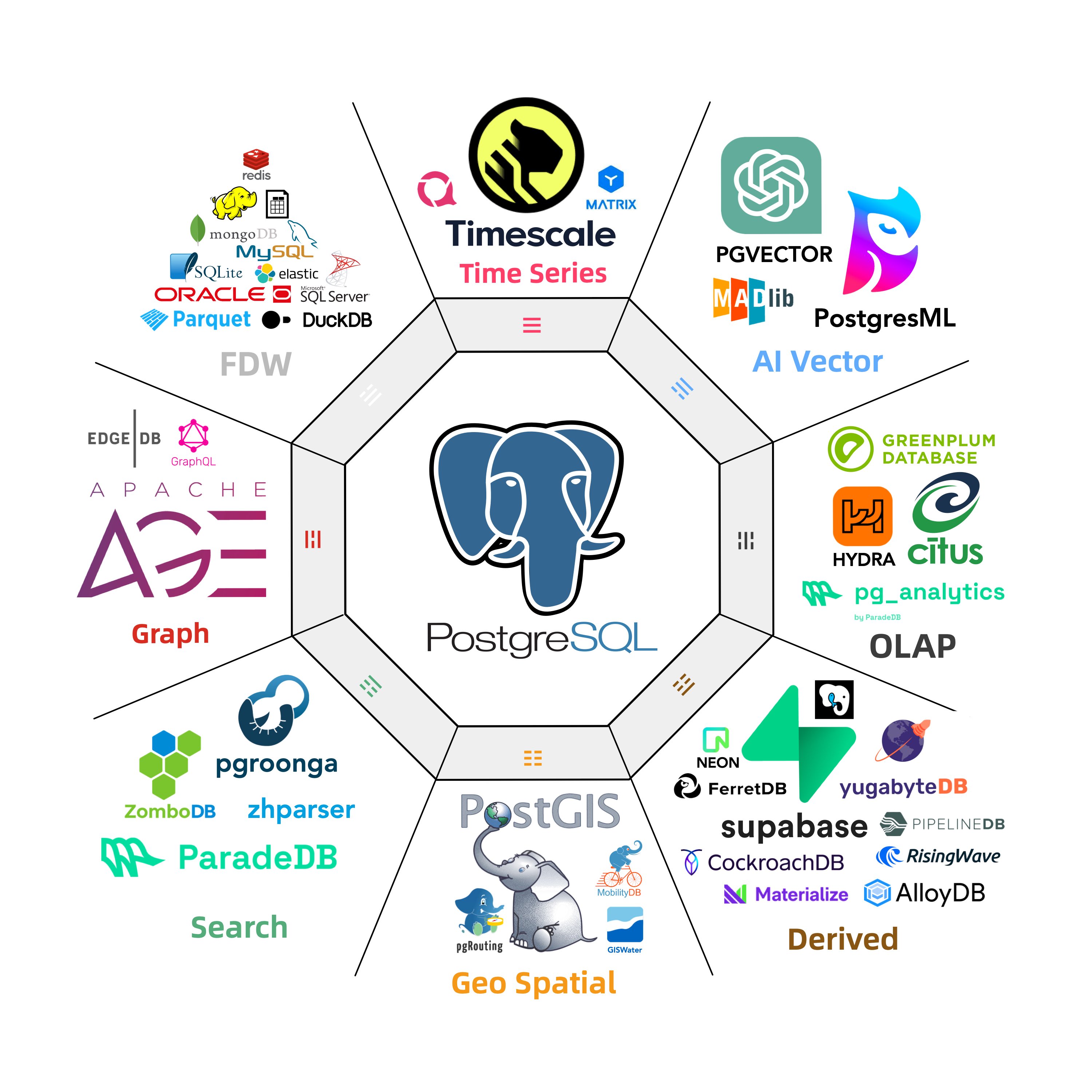

- Postgres is eating the database world

- Technical Minimalism: Just Use PostgreSQL for Everything

- ParadeDB: ElasticSearch Alternative in PG Ecosystem

- The Astonishing Scalability of PostgreSQL

- PostgreSQL Crowned Database of the Year 2024!

- PostgreSQL Convention 2024

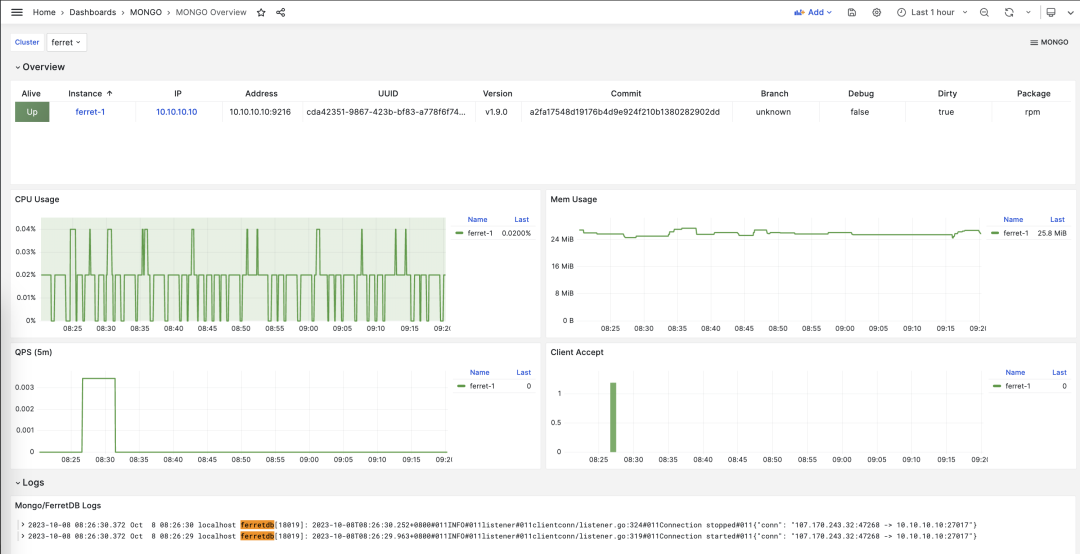

- FerretDB: When PG Masquerades as MongoDB

- PostgreSQL, The most successful database

- How Powerful Is PostgreSQL?

- Why Is PostgreSQL the Most Successful Database?

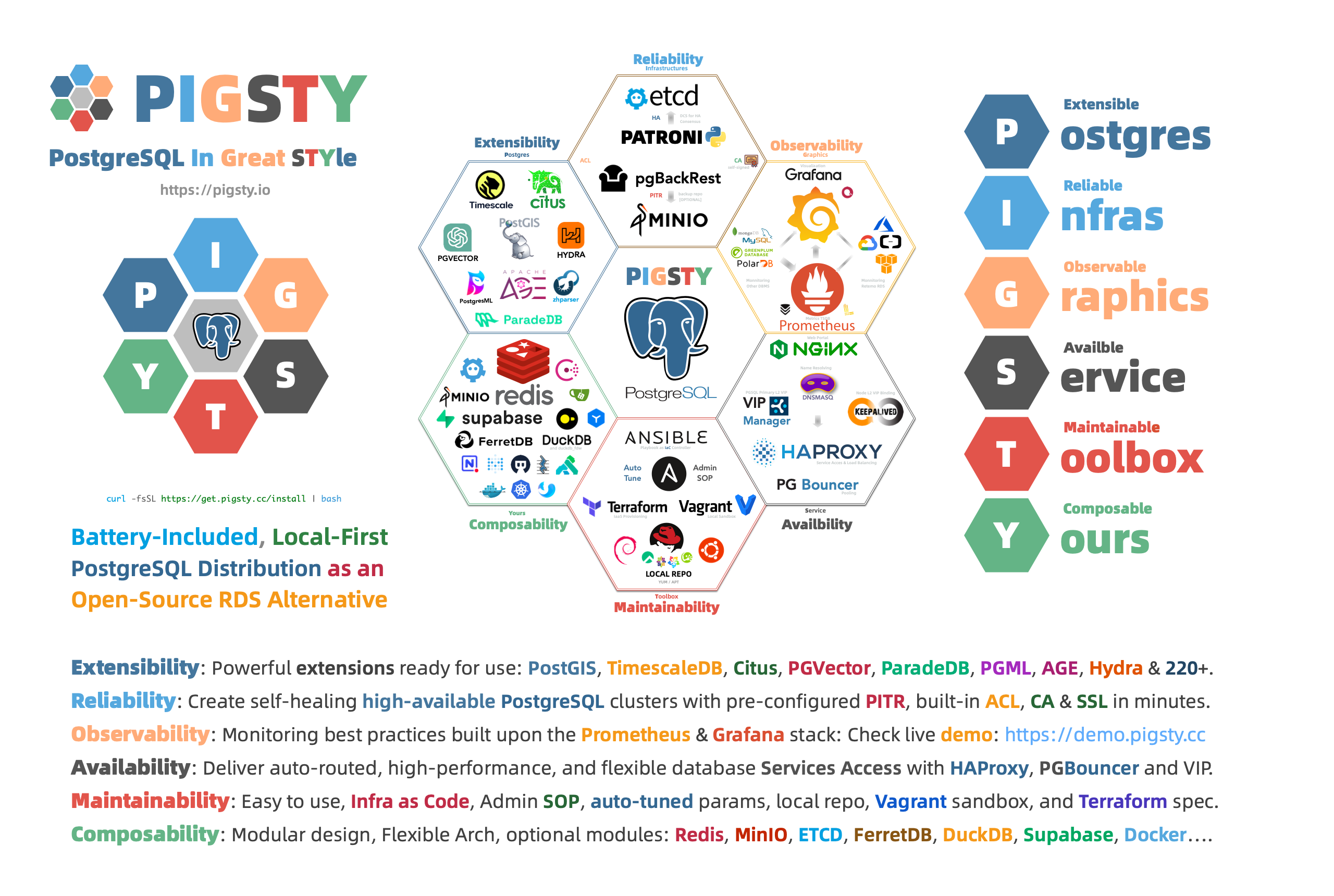

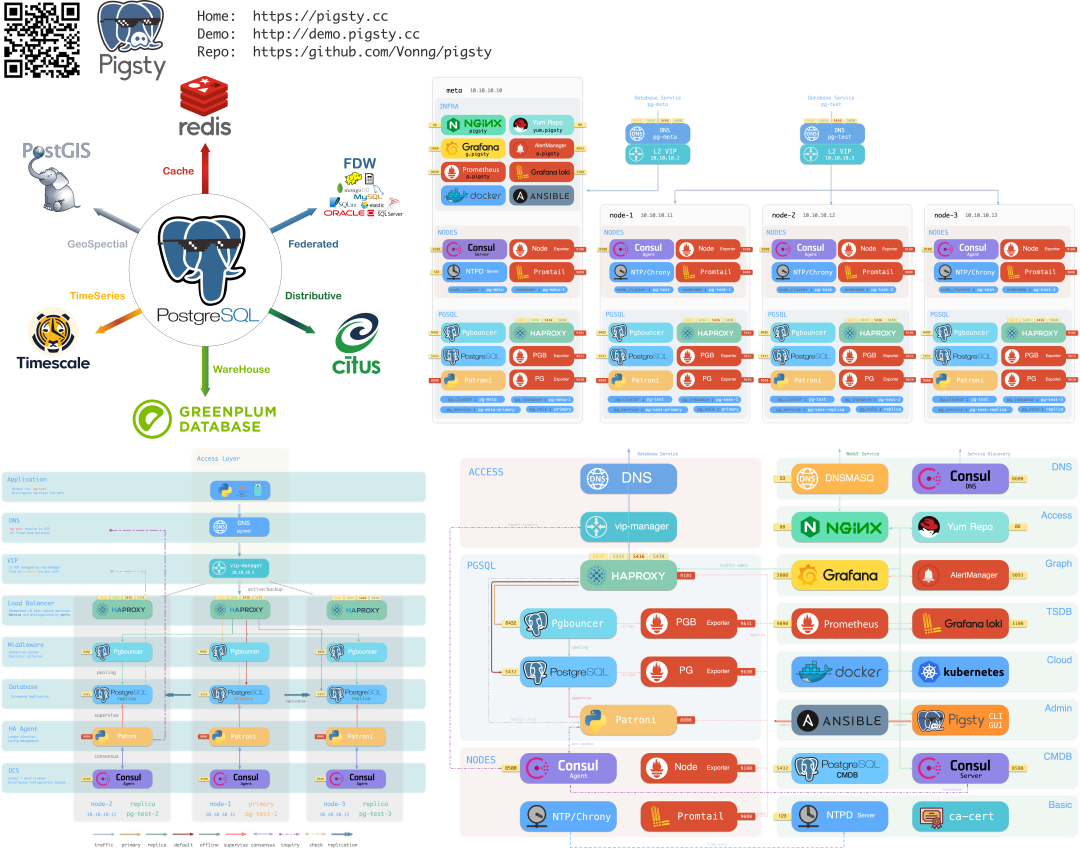

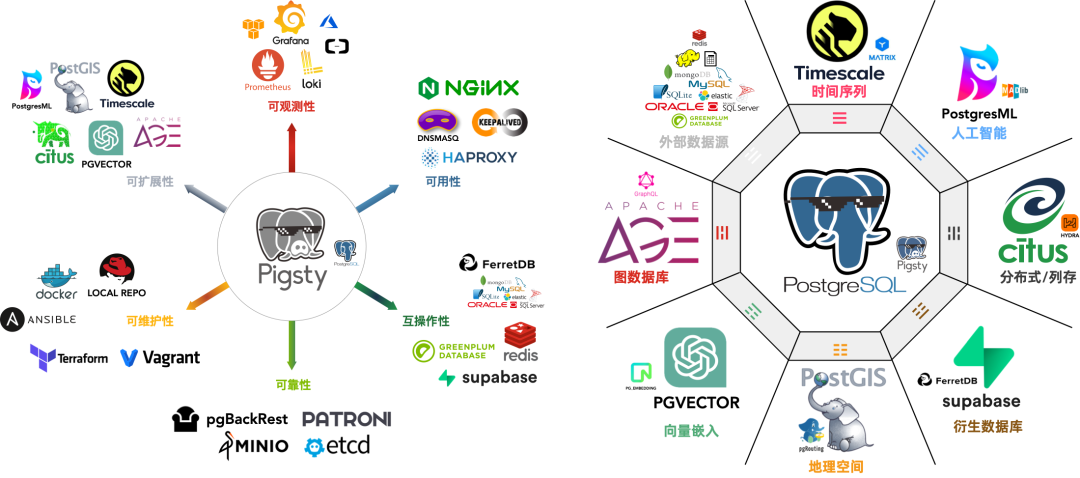

- Pigsty: The Production-Ready PostgreSQL Distribution

- Why PostgreSQL Has a Bright Future

- What Makes PostgreSQL So Awesome?

- PG Admin

- PG Logical Replication Explained

- Query Optimization: The Macro Approach with pg_stat_statements

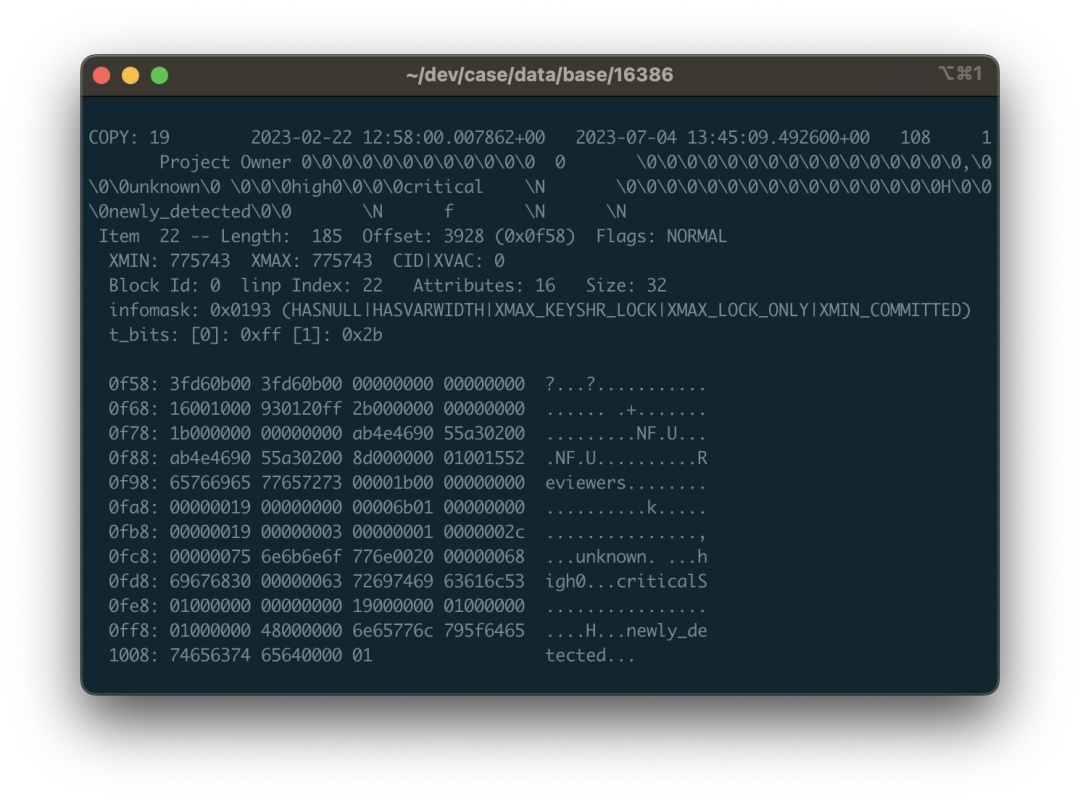

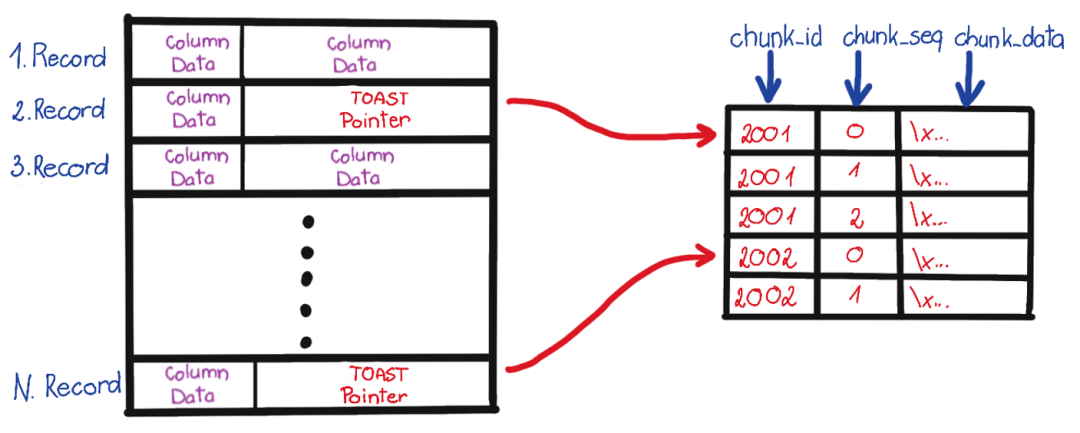

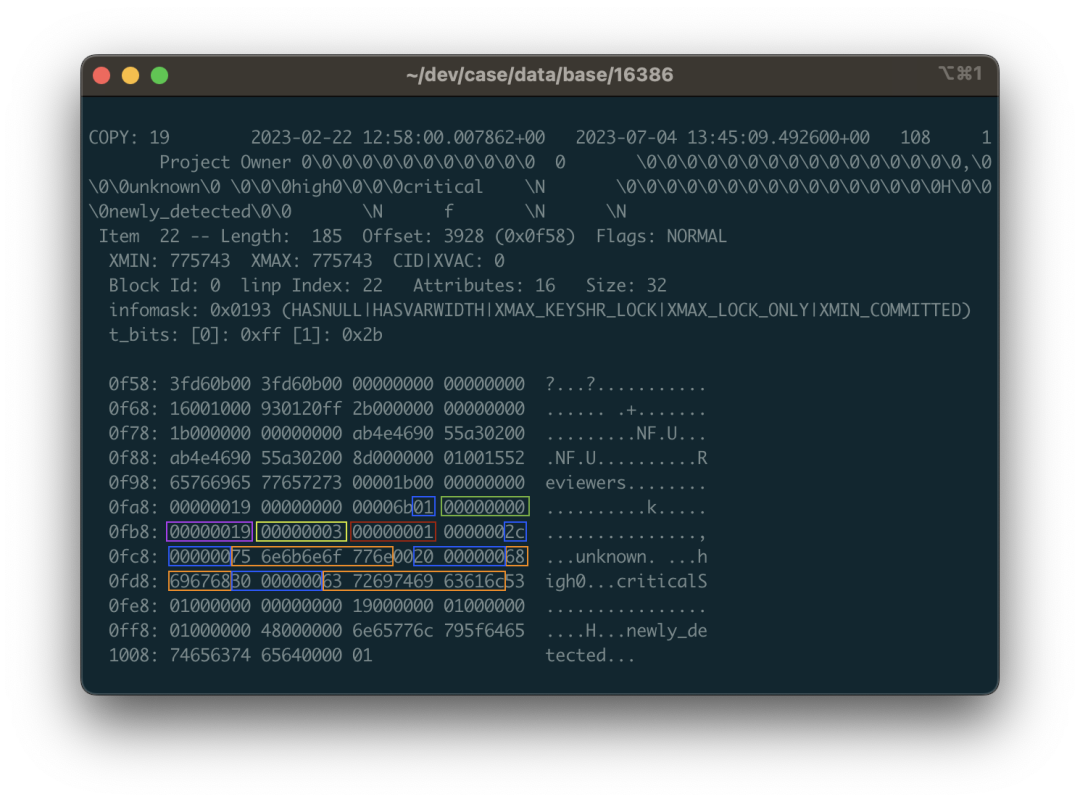

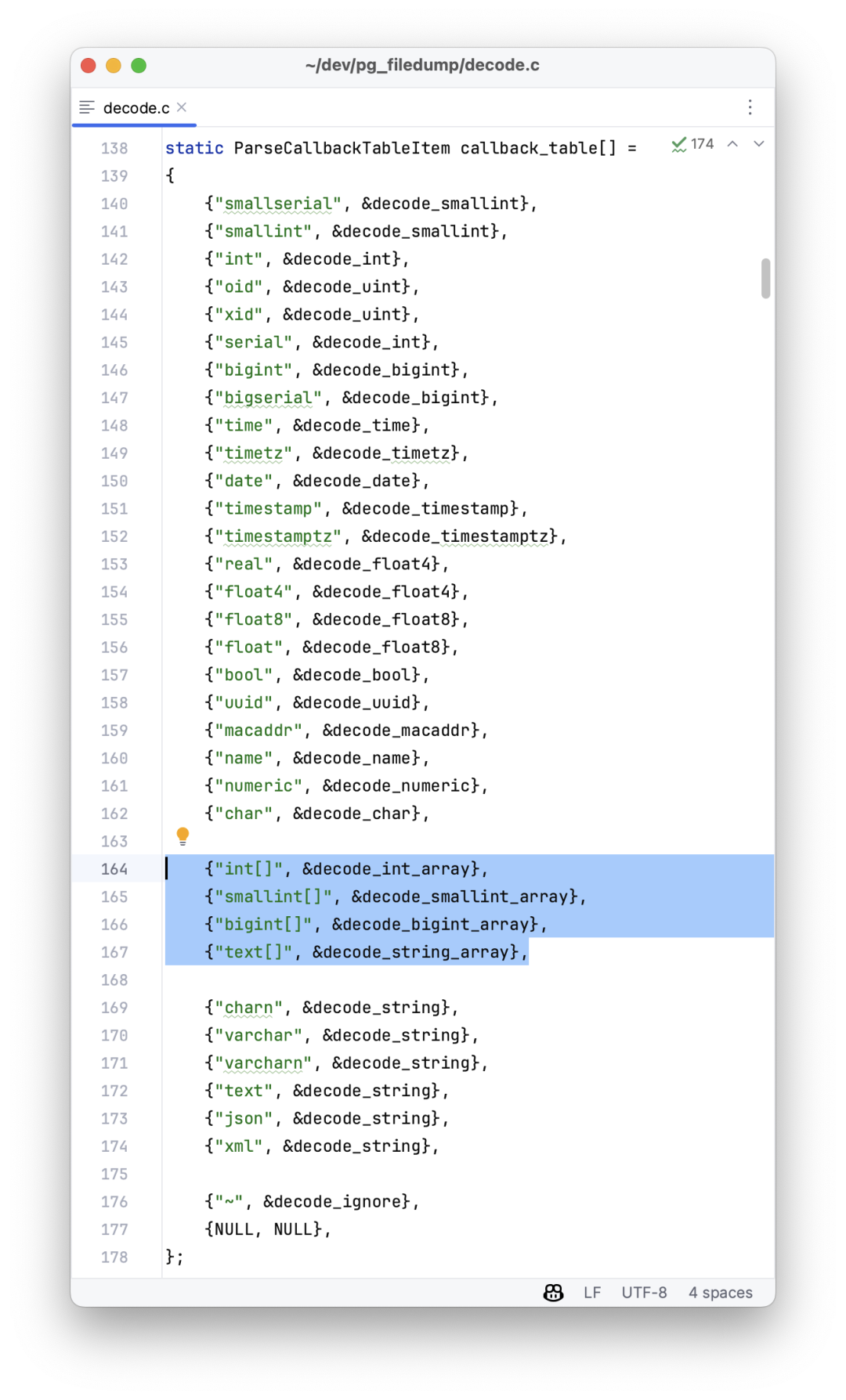

- Rescue Data with pg_filedump?

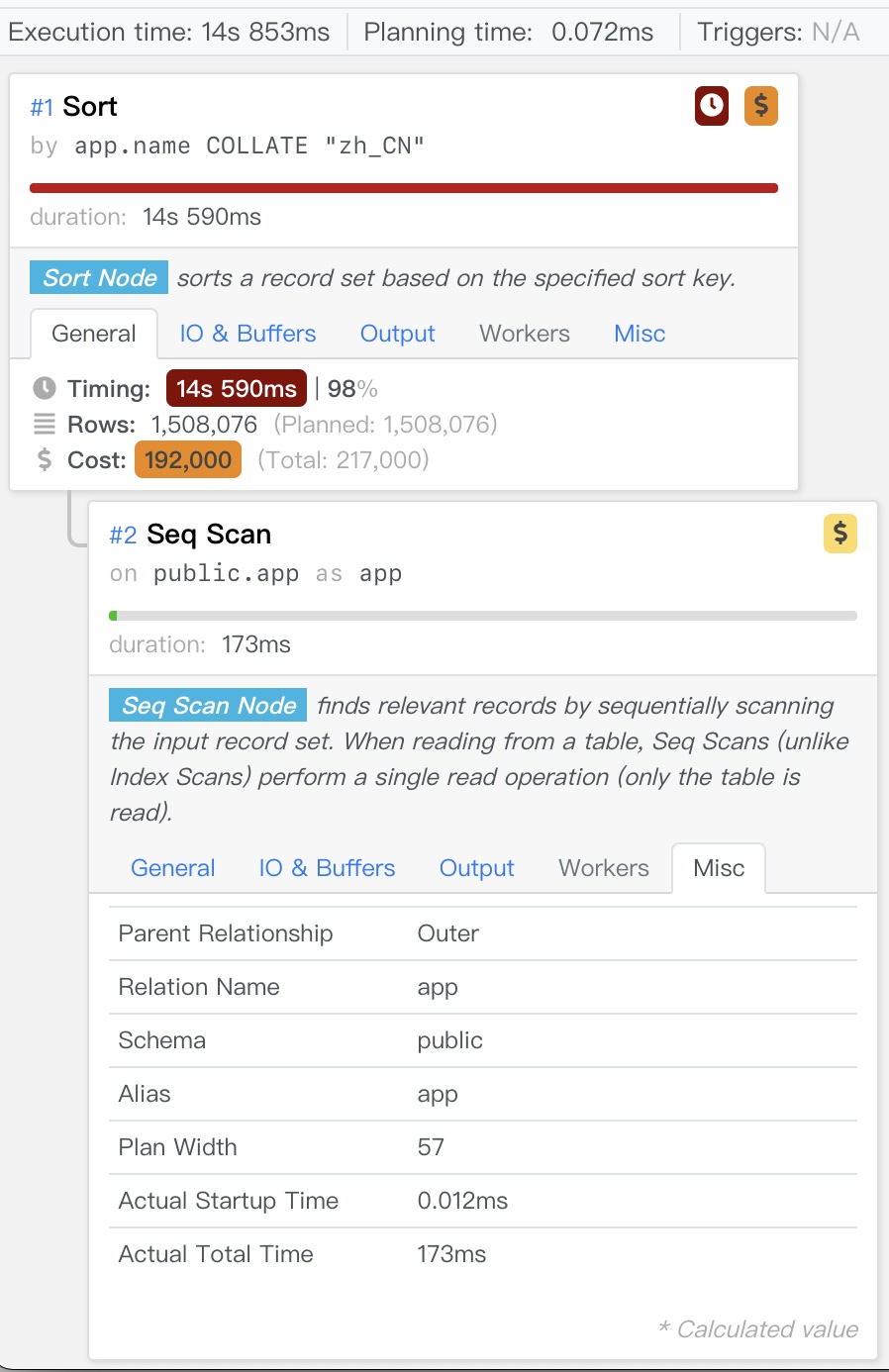

- Collation in PostgreSQL

- PostgreSQL Replica Identity Explained

- Slow Query Diagnosis

- Releases

- v3.4: MySQL Wire-Compatibility and Improvements

- v3.3:Extension 404,Odoo, Dify, Supabase, Nginx Enhancement

- v3.2: The pig CLI, ARM64 Repo, Self-hosting Supabase

- v3.1: PG 17 as default, Better Supabase & MinIO, ARM & U24 support

- Pigsty v3.0: Extension Exploding & Plugable Kernels

- v2.7: Extension Overwhelming

- v2.6: the OLAP New Challenger

- v2.5: Debian / Ubuntu / PG16

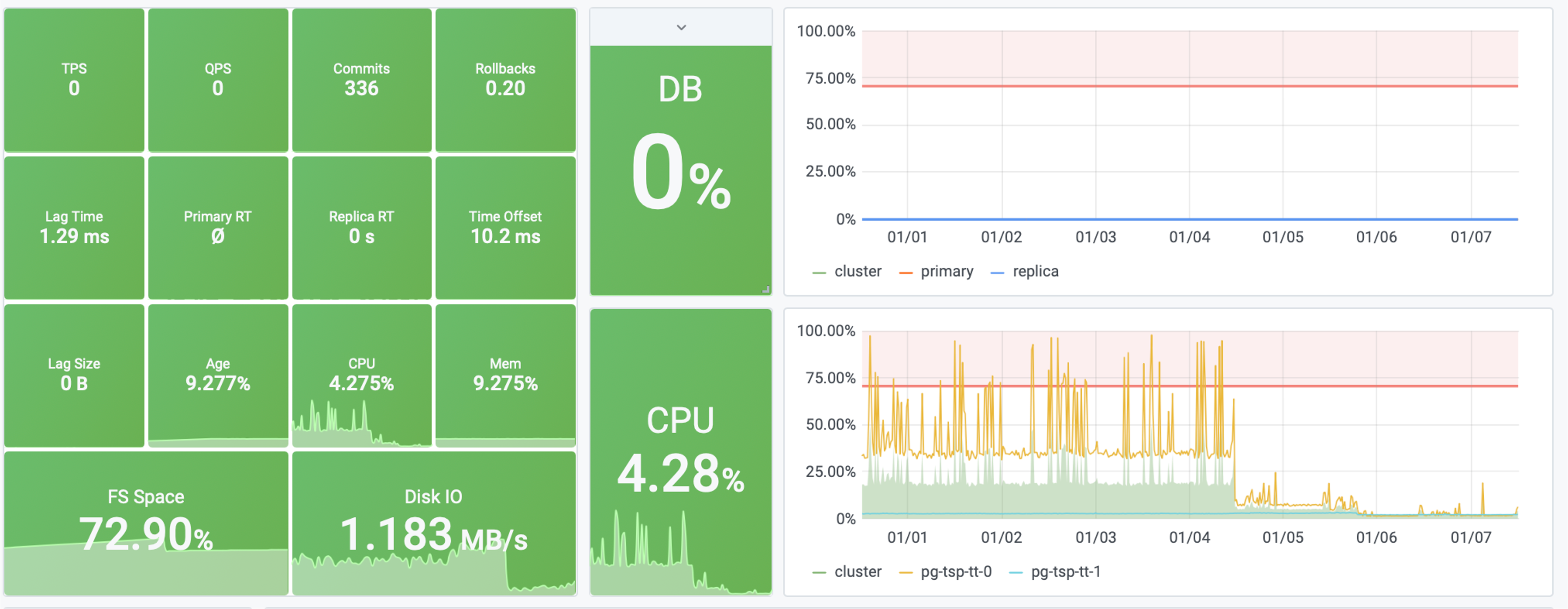

- v2.4: Monitoring Cloud RDS

- v2.3: Ecosystem Applications

- v2.2: Observability Overhaul

- v2.1: Vector Embedding & RAG

- v2.0: Free RDS PG Alternative

- v1.5.0 Release Note

- v1.4.0 Release Note

- v1.3.0 Release Note

- v1.2.0 Release Note

- v1.1.0 Release Note

- v1.0.0 Release Note

- v0.9.0 Release Note

- v0.8.0 Release Note

- v0.7.0 Release Note

- v0.6.0 Release Note

- v0.5.0 Release Note

- v0.4.0 Release Note

- v0.3.0 Release Note

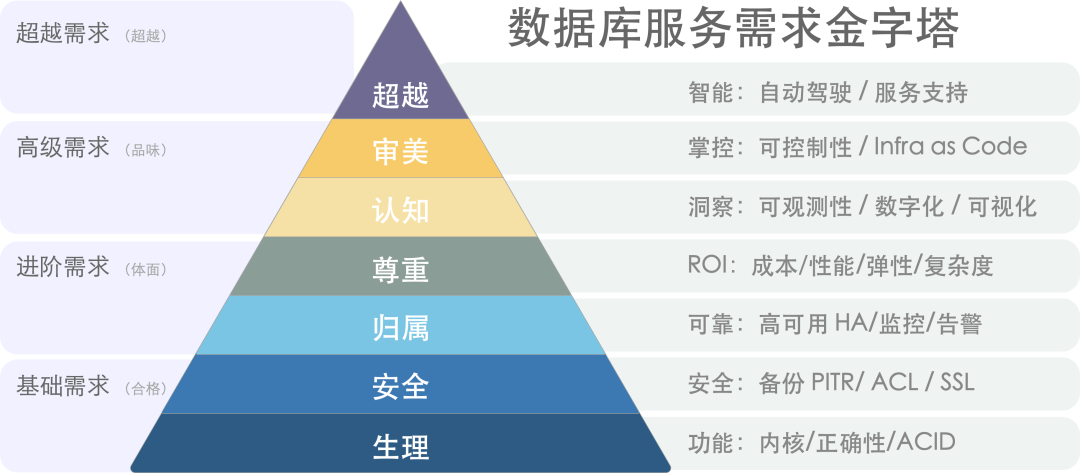

Database

Scaling Postgres to the next level at OpenAI

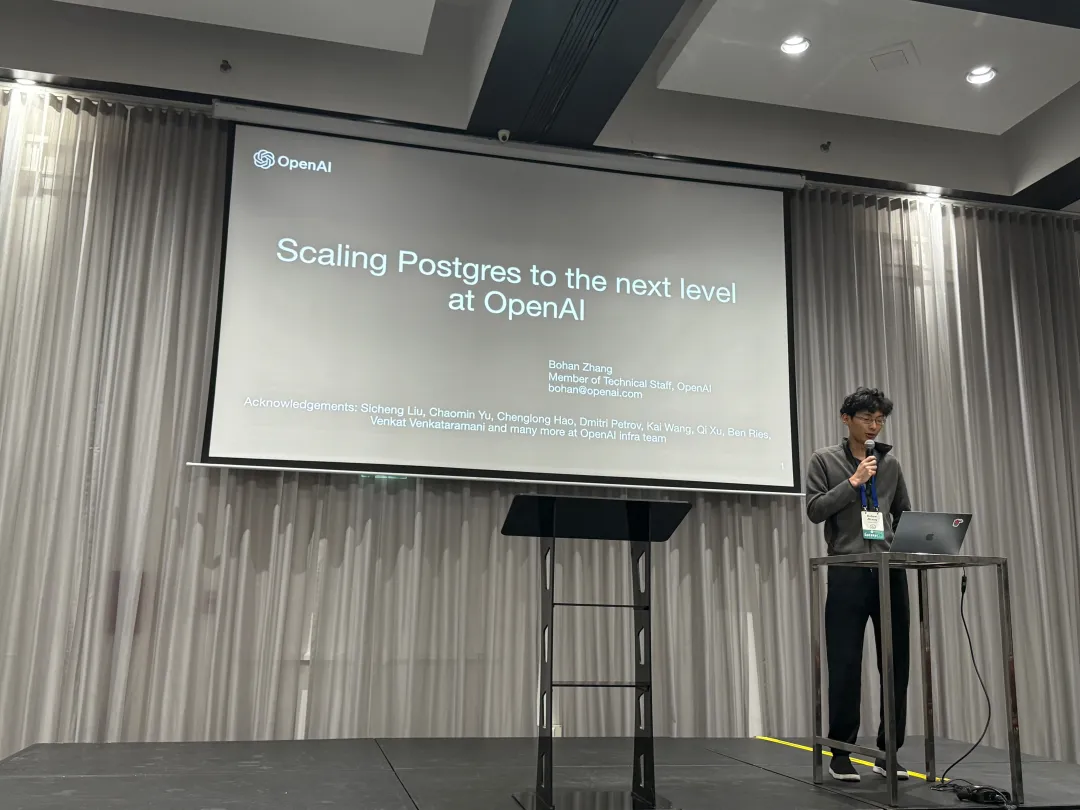

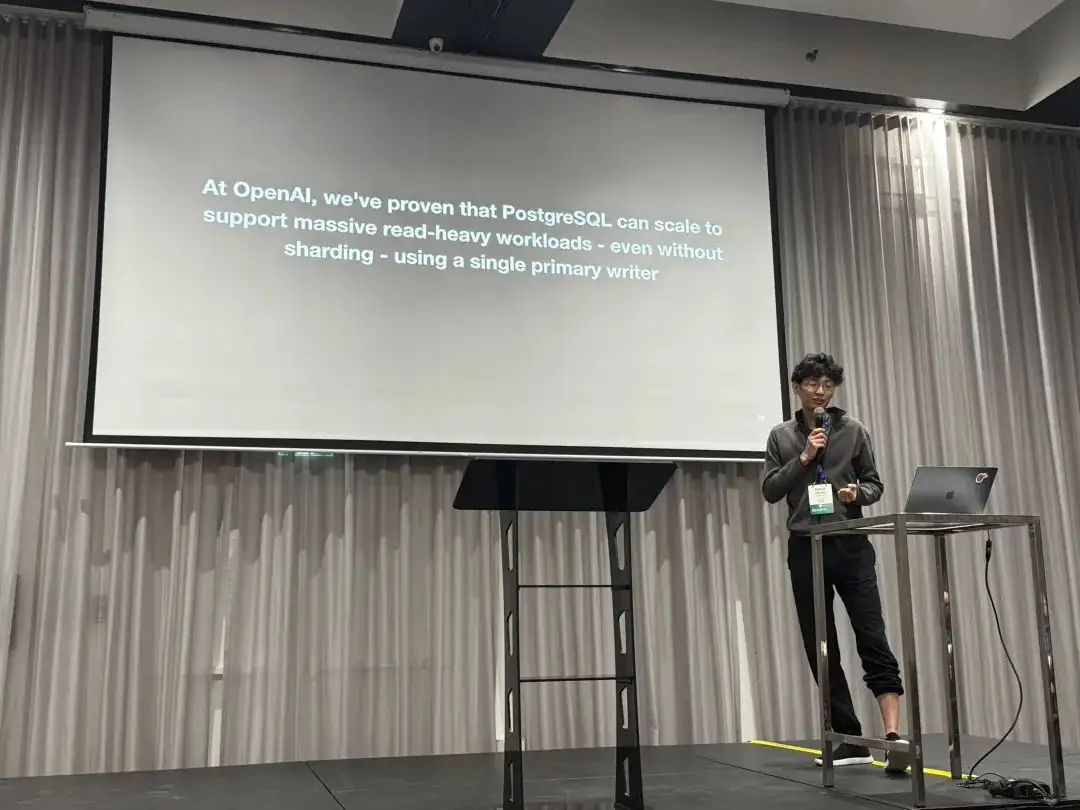

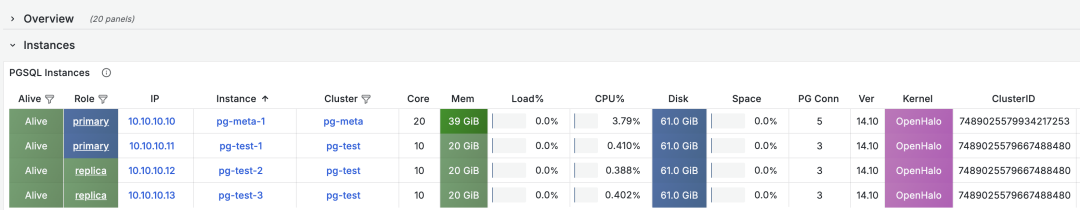

At PGConf.Dev 2025, Bohan Zhang from OpenAI shared a session titled Scaling Postgres to the next level at OpenAI, giving us a peek into the database usage of a top-tier unicorn.

“At OpenAl, we’ve proven that PostgreSQL can scale to support massive read-heavy workloads - even without sharding - using a single primary writer”

—— Bohan Zhang from OpenAI, PGConf.Dev 2025

Bohan Zhang is a member of the OpenAI Infra team, student of Andy Pavlo, and co-found OtterTune with him.

This article is based on Bohan’s presentation at the conference. with chinese translation/commentary by Ruohang Feng (Vonng): Author of Pigsty. The original chinese version is available on WeChat Column and Pigsty CN Blog.

Hacker News Discussion: OpenAI: Scaling Postgres to the Next Level

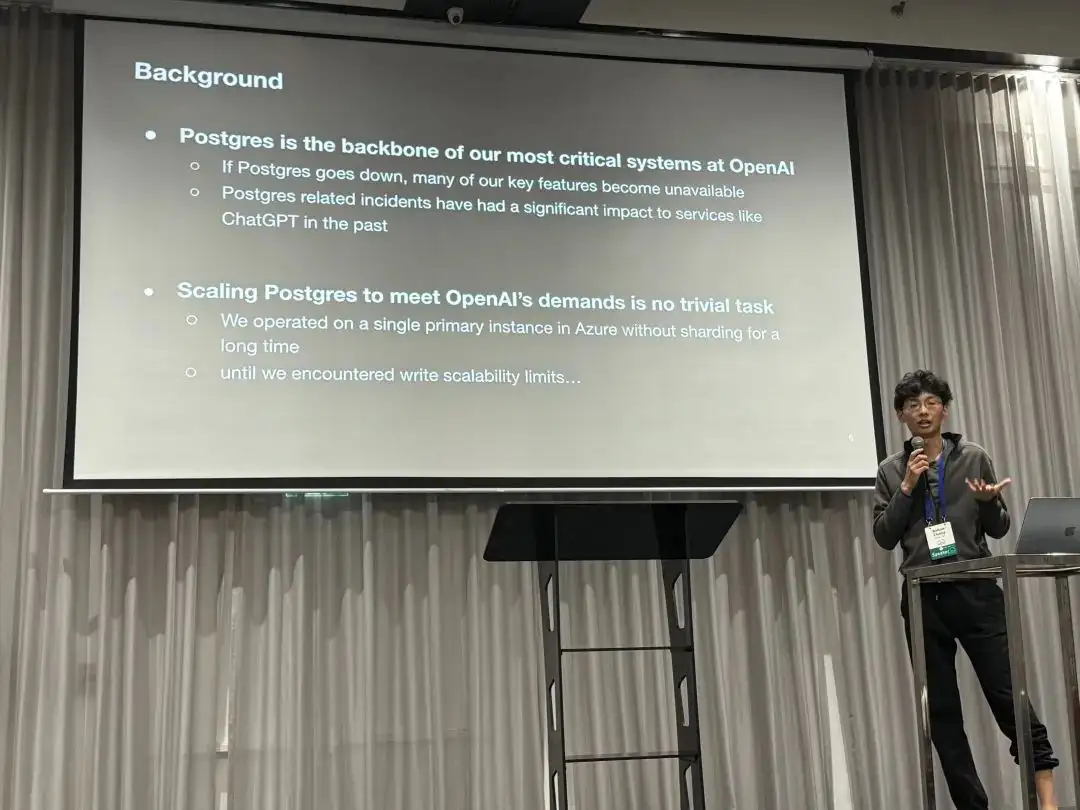

Background

Postgres is the backbone of our most critical systems at OpenAl. If Postgres goes down, many of OpenAI’s key features go down with it — and there’s plenty of precedent for this. PostgreSQL-related failures have caused several ChatGPT outages in the past.

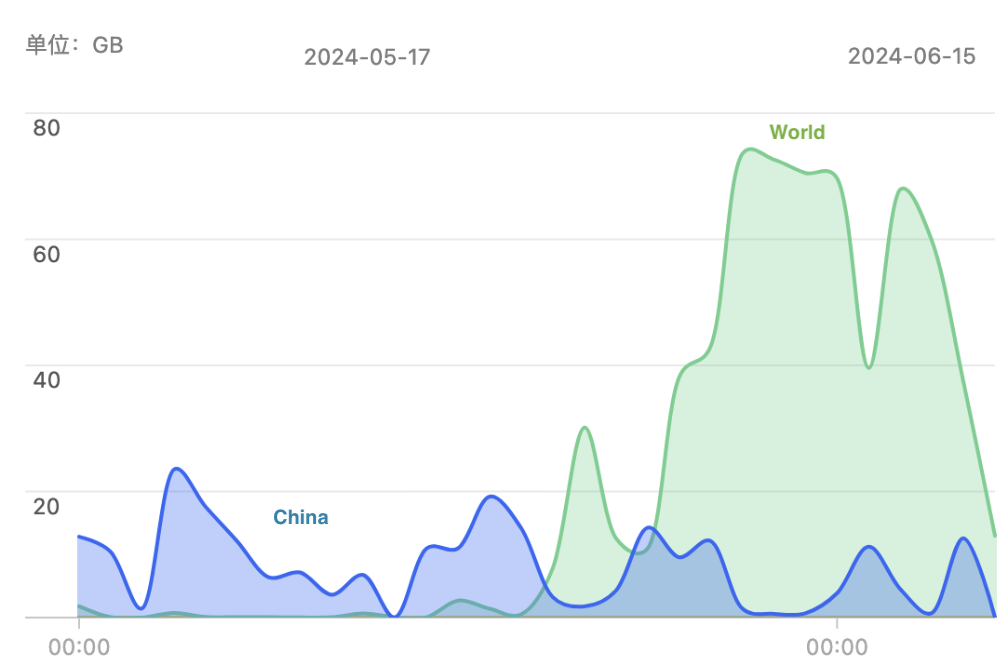

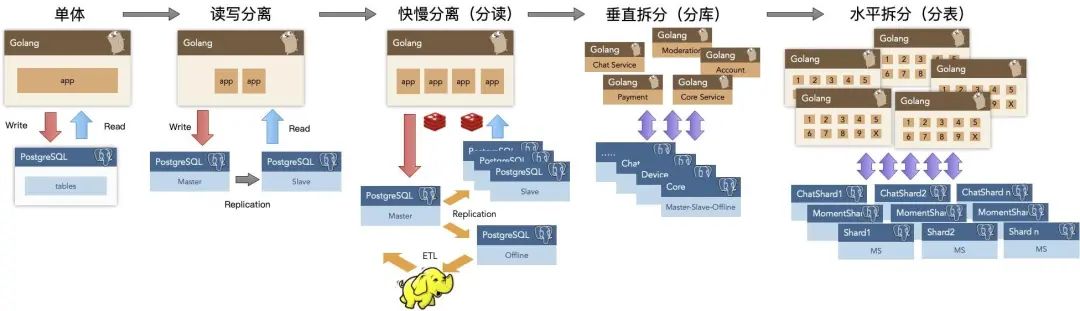

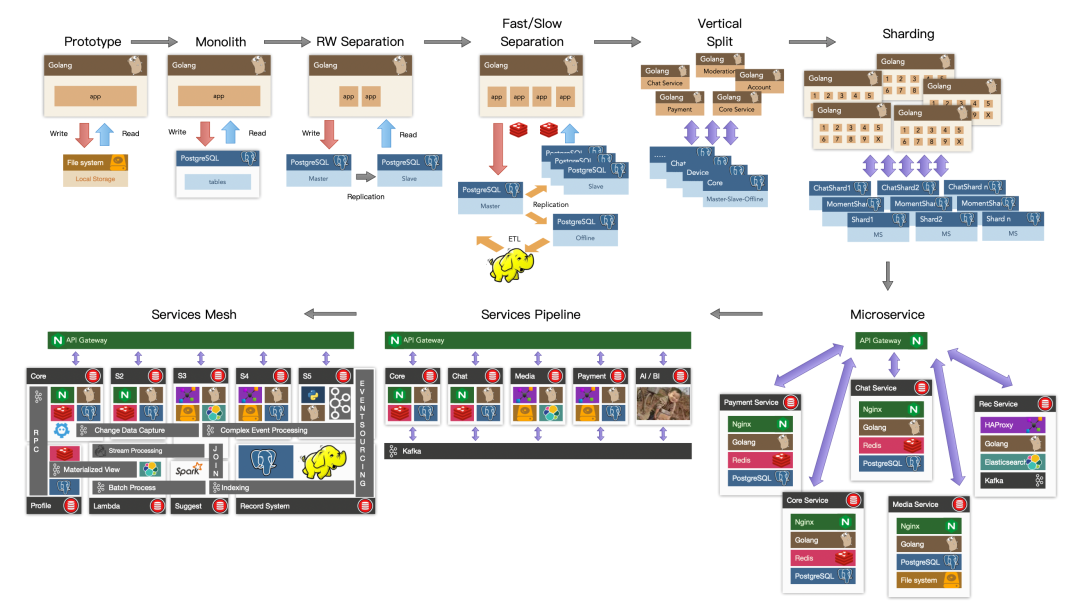

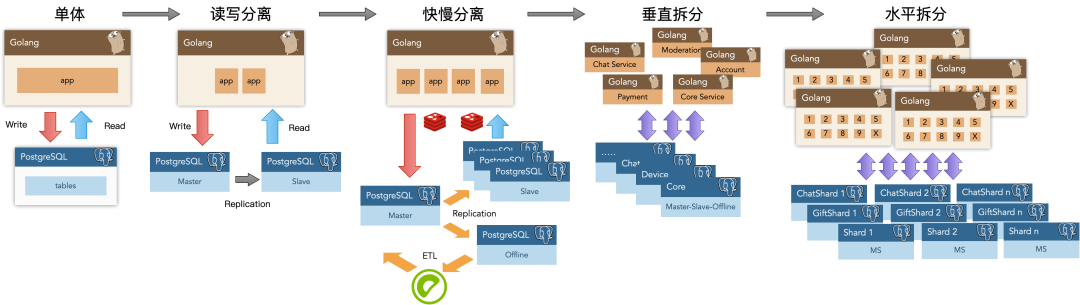

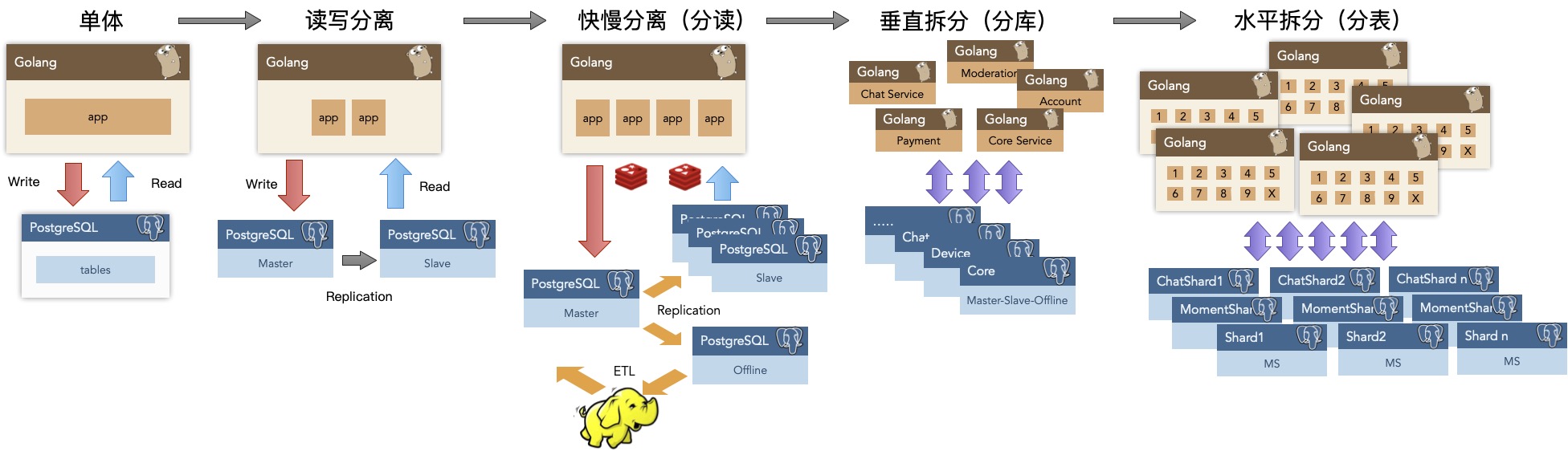

OpenAI uses managed PostgreSQL databases on Azure, without sharding. Instead, they employ a classic primary-replica replication architecture with one primary and over dozens of read replicas. For a service with several hundred million active users like OpenAI, scalability is a major concern.

Challenges

In OpenAI’s PostgreSQL architecture, read scalability is excellent, but “write requests” have become the primary bottleneck. OpenAI has already made many optimizations here, such as offloading write workloads wherever possible and avoiding placing new business logic into the main database.

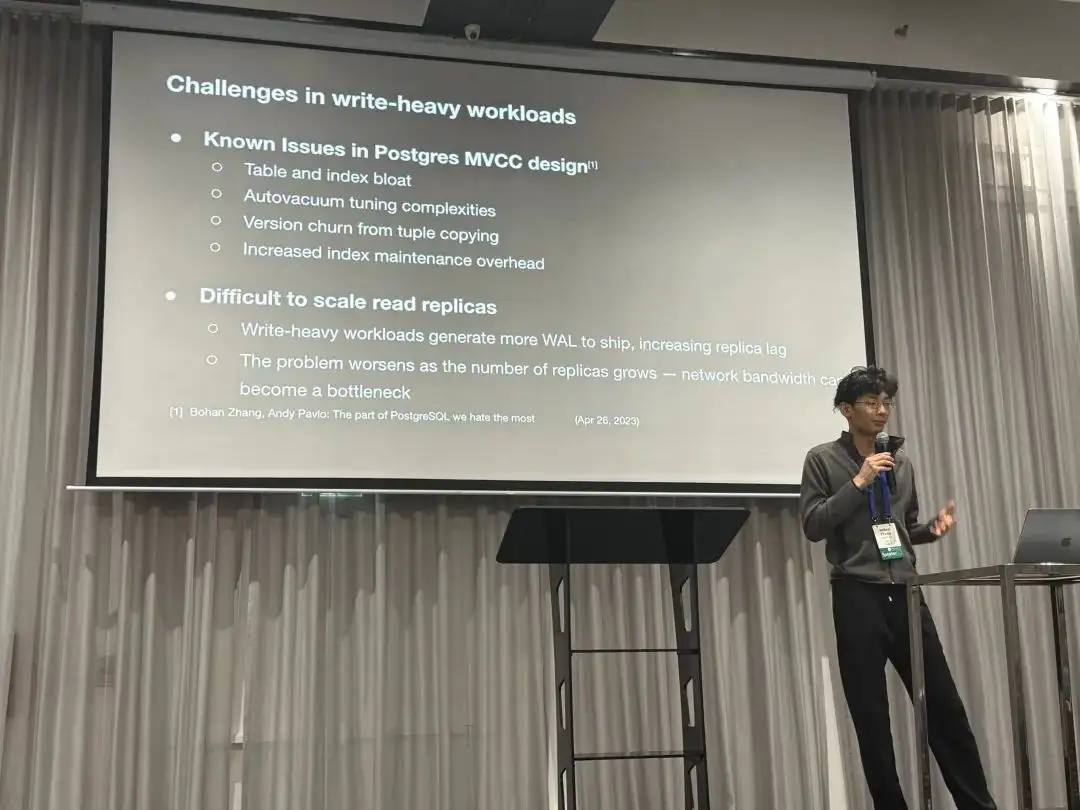

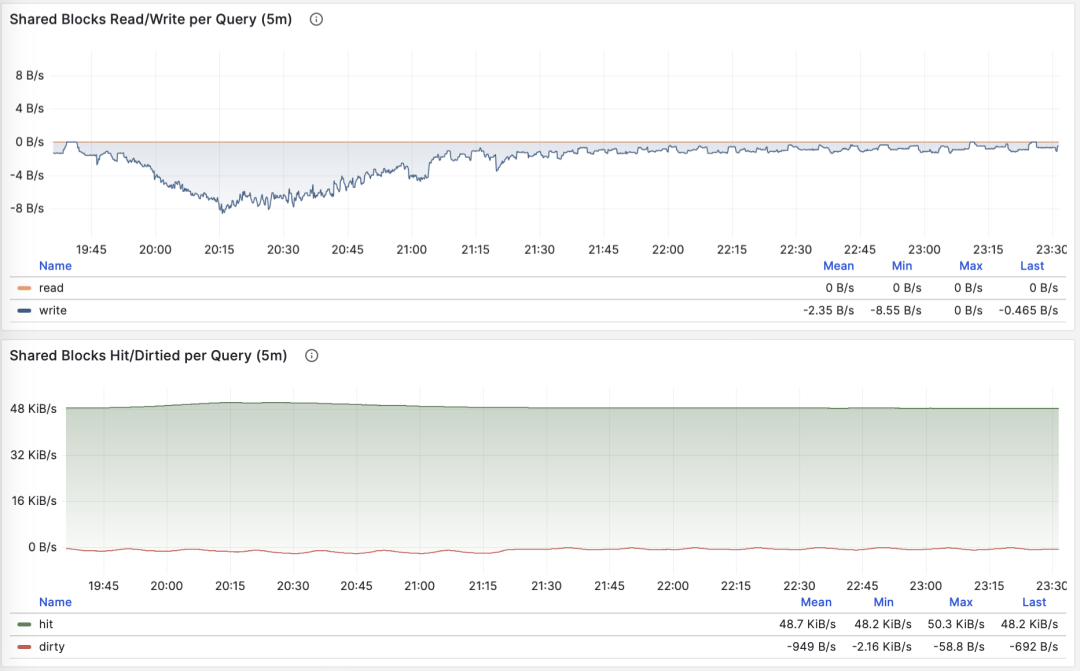

PostgreSQL’s MVCC design has some known issues, such as table and index bloat. Tuning autovacuum is complex, and every write generates a completely new version of a row. Index access might also require additional heap fetches for visibility checks. These design choices create challenges for scaling read replicas: for instance, more WAL typically leads to greater replication lag, and as the number of replicas grows, network bandwidth can become the new bottleneck.

Measures

To tackle these issues, we’ve made efforts on multiple fronts:

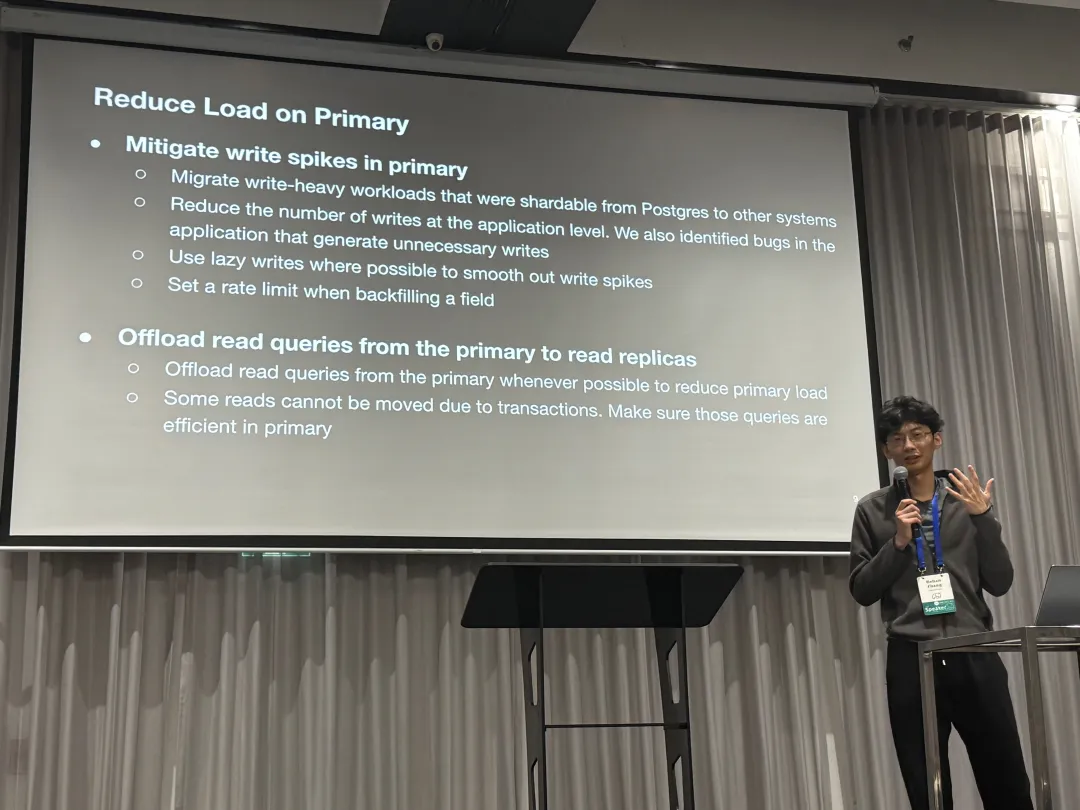

Reduce Load on Primary

The first optimization is to smooth out write spikes on the primary and minimize its load as much as possible, for example:

- Offloading all possible writes.

- Avoiding unnecessary writes at the application level.

- Using lazy writes to smooth out write bursts.

- Controlling the rate of data backfilling.

Additionally, OpenAI offloads as many read requests as possible to replicas. The few read requests that cannot be moved from the primary because they are part of read-write transactions are required to be as efficient as possible.

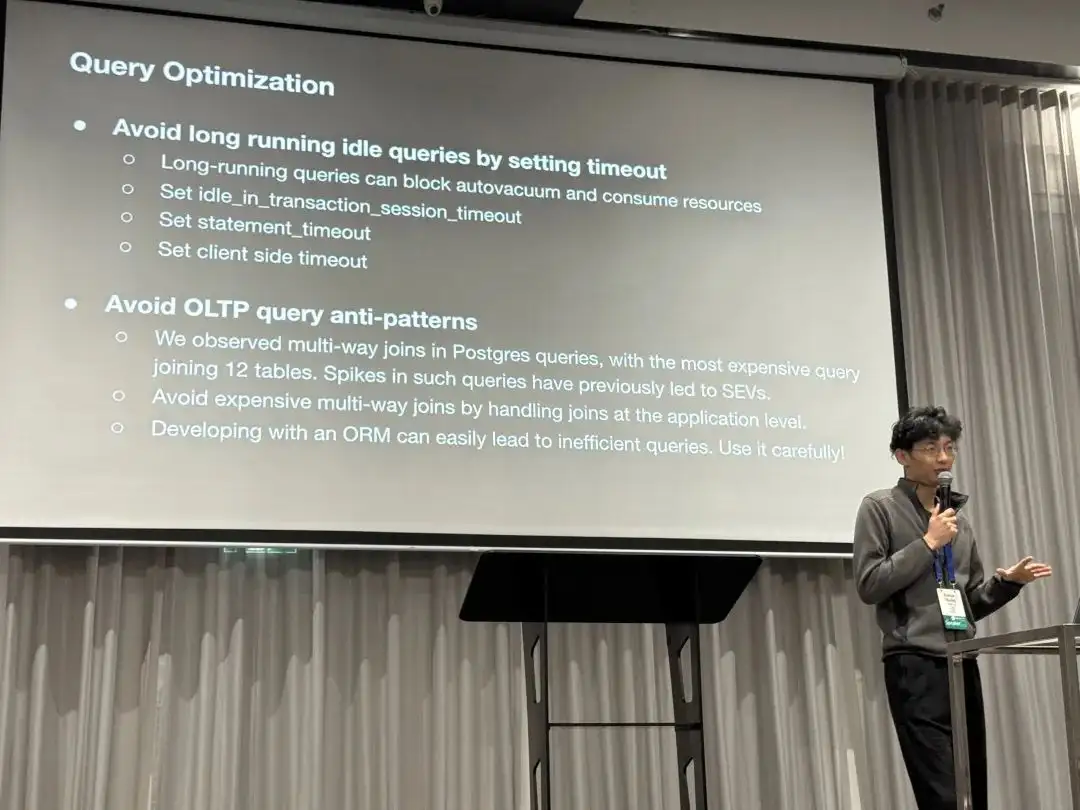

Query Optimization

The second area is query-level optimization. Since long-running transactions can block garbage collection and consume resources, they use timeout settings to prevent long “idle in transaction” states and set session, statement, and client-level timeouts. They also optimized some multi-way JOIN queries (e.g., joining 12 tables at once). The talk specifically mentioned that using ORMs can easily lead to inefficient queries and should be used with caution.

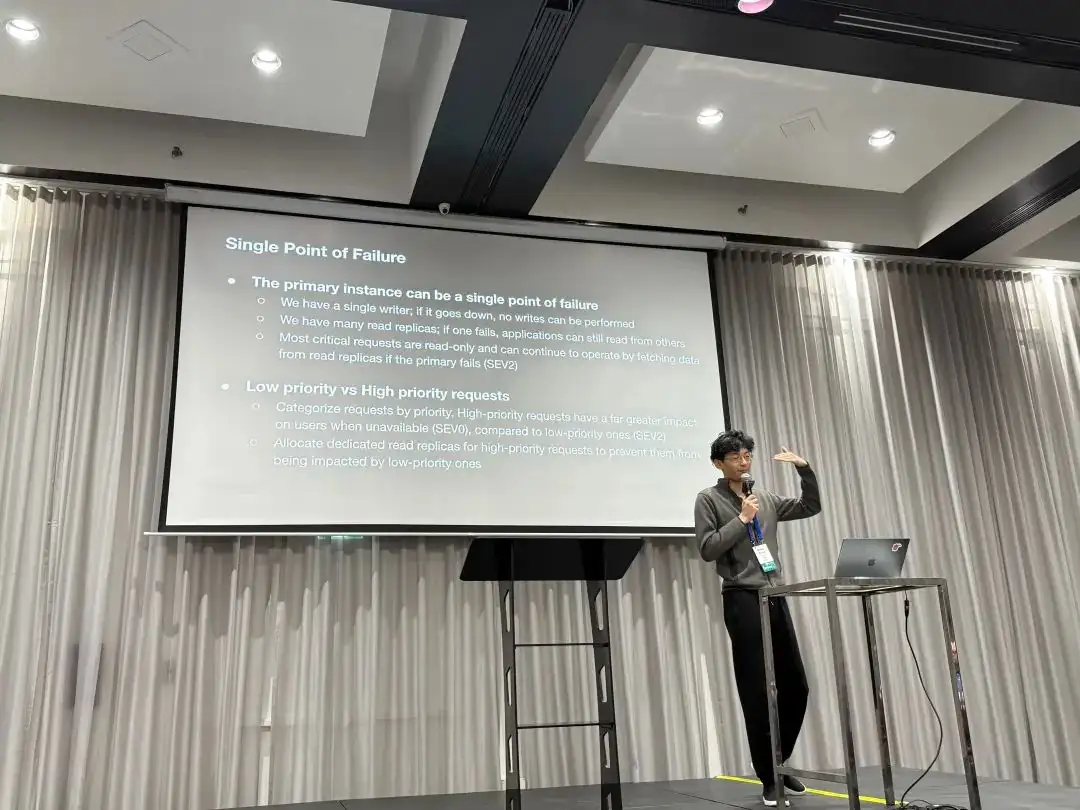

Mitigating Single Points of Failure

The primary is a single point of failure; if it goes down, writes are blocked. In contrast, we have many read-only replicas. If one fails, applications can still read from others. In fact, many critical requests are read-only, so even if the primary goes down, they can continue to serve reads.

Furthermore, we’ve distinguished between low-priority and high-priority requests. For high-priority requests, OpenAI allocates dedicated read-only replicas to prevent them from being impacted by low-priority ones.

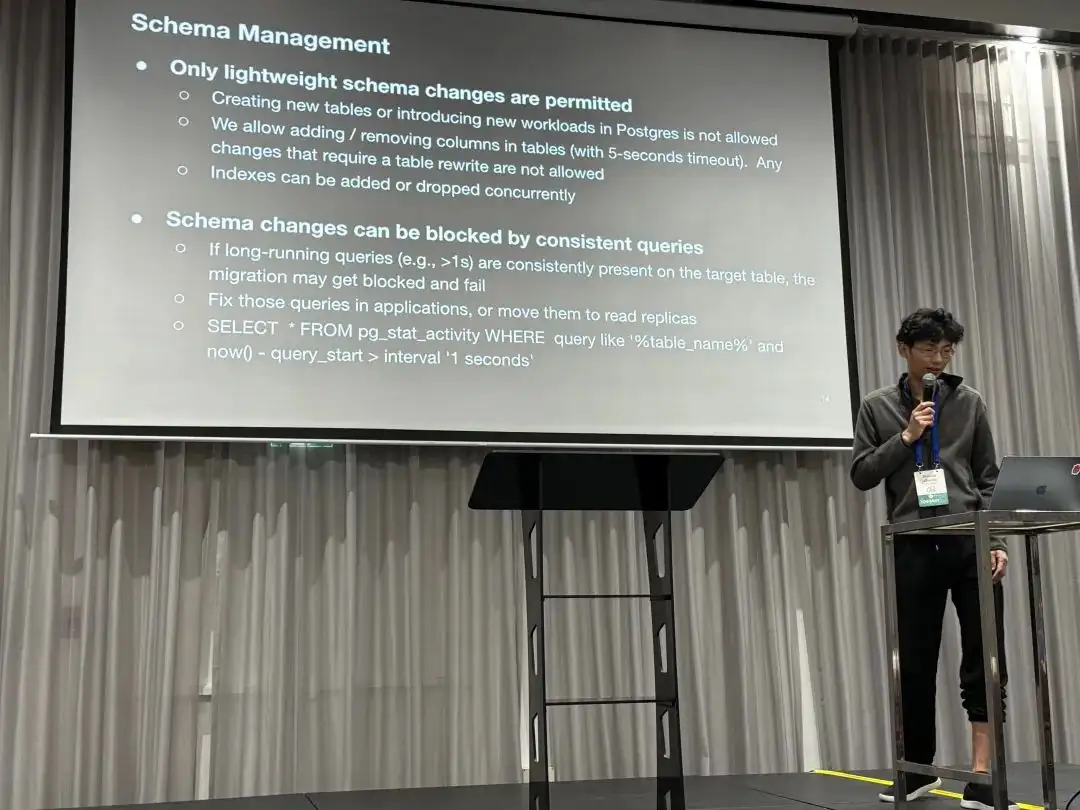

Schema Management

The fourth measure is to allow only lightweight schema changes on this cluster. This means:

- Creating new tables or adding new workloads to it is not allowed.

- Adding or removing columns is allowed (with a 5-second timeout), but any operation that requires a full table rewrite is forbidden.

- Creating or removing indexes is allowed, but must be done using

CONCURRENTLY.

Another issue mentioned was that persistent long-running queries (>1s) would continuously block schema changes, eventually causing them to fail. The solution was to have the application optimize or move these slow queries to replicas.

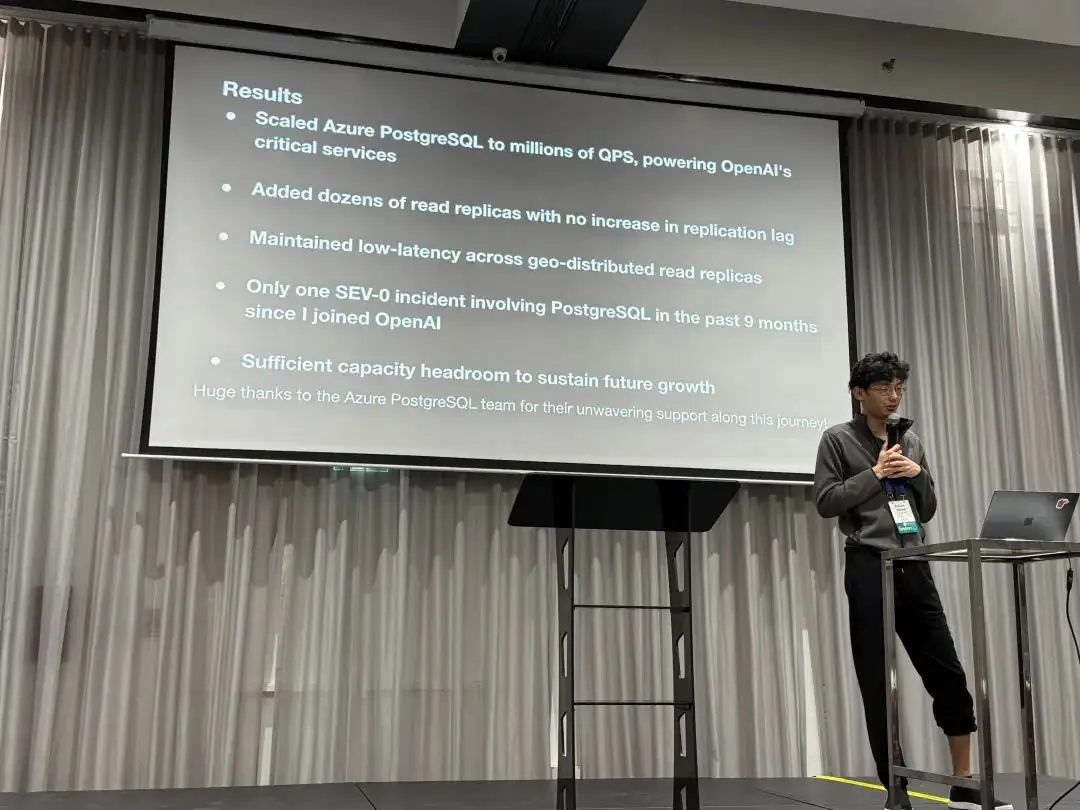

Results

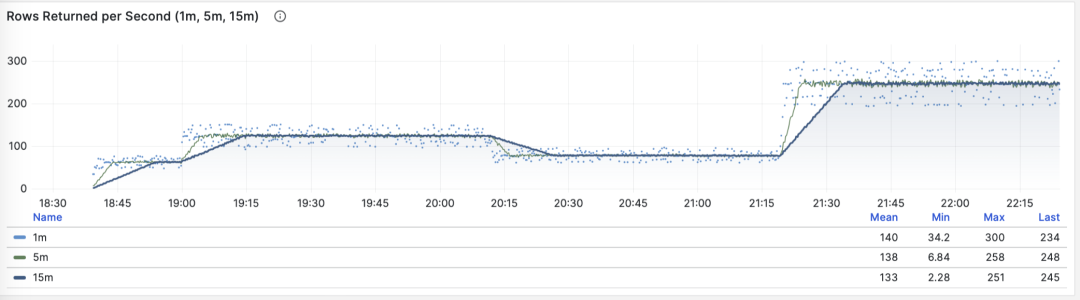

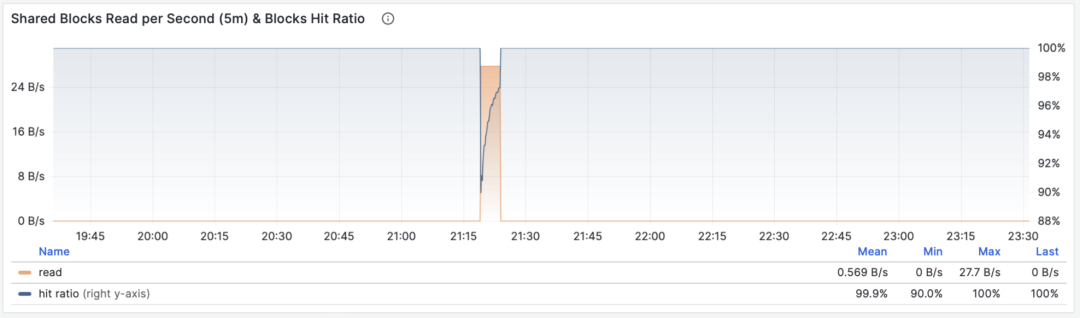

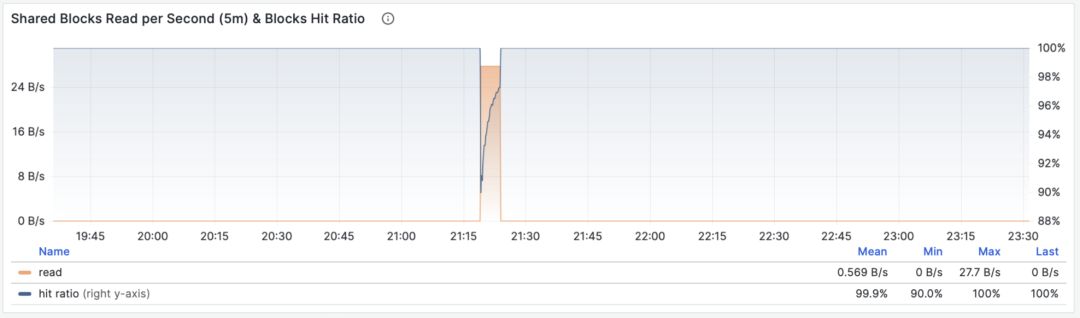

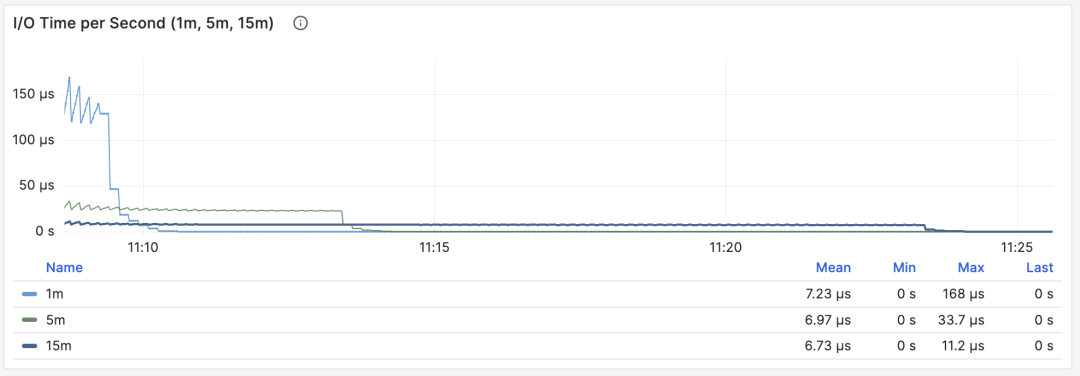

- Scaled PostgreSQL on Azure to millions of QPS, supporting OpenAI’s critical services.

- Added dozens of replicas without increasing replication lag.

- Deployed read-only replicas to different geographical regions while maintaining low latency.

- Only one SEV0 incident related to PostgreSQL in the past nine months.

- Still have plenty of room for future growth.

“At OpenAl, we’ve proven that PostgreSQL can scale to support massive read-heavy workloads - even without sharding - using a single primary writer”

Case Studies

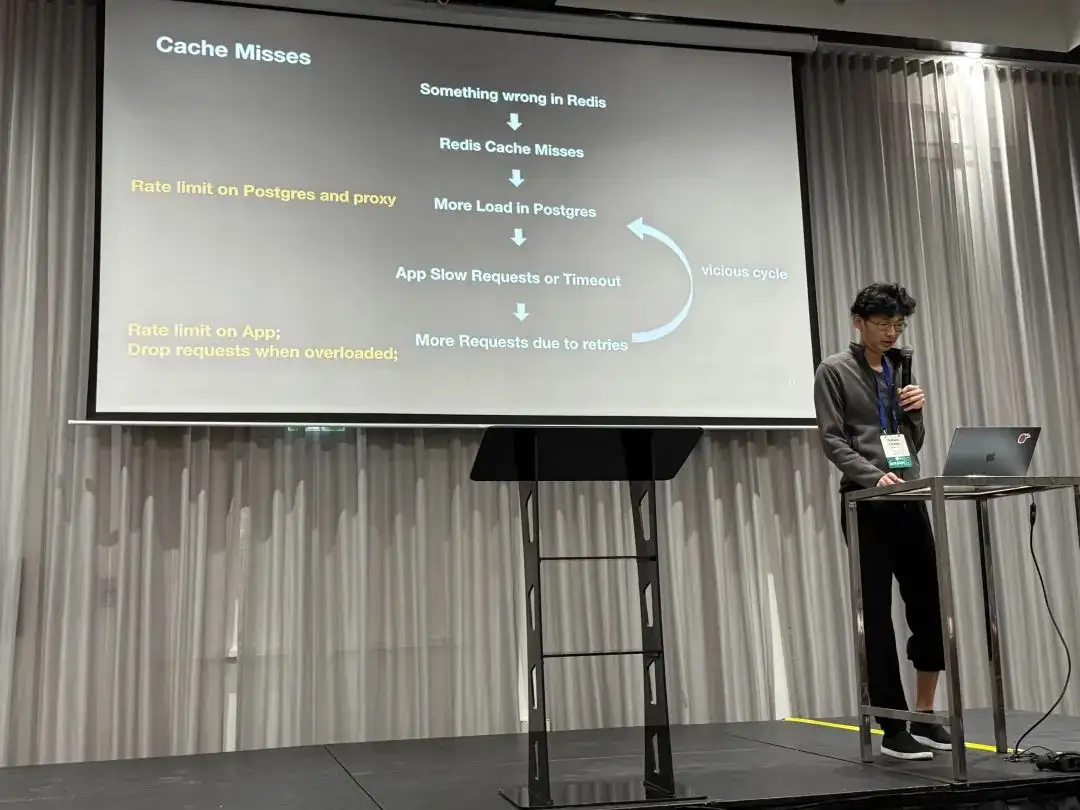

OpenAI also shared a few case studies of failures they’ve faced. The first was a cascading failure caused by a redis outage.

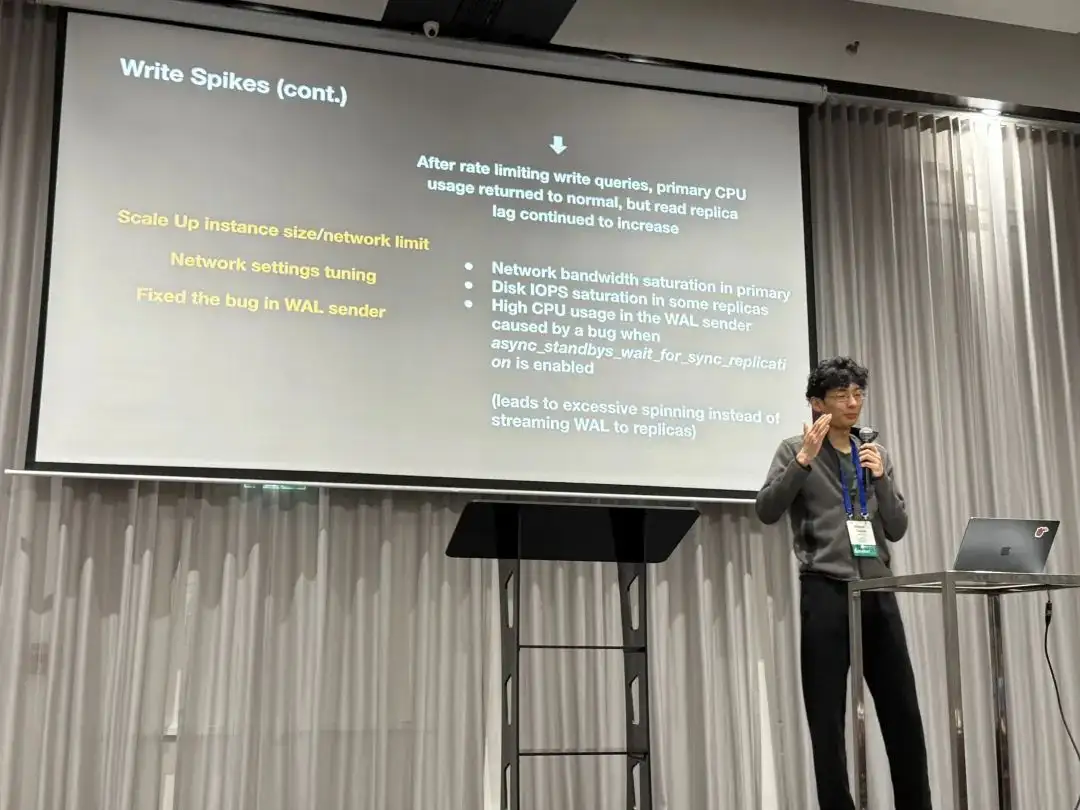

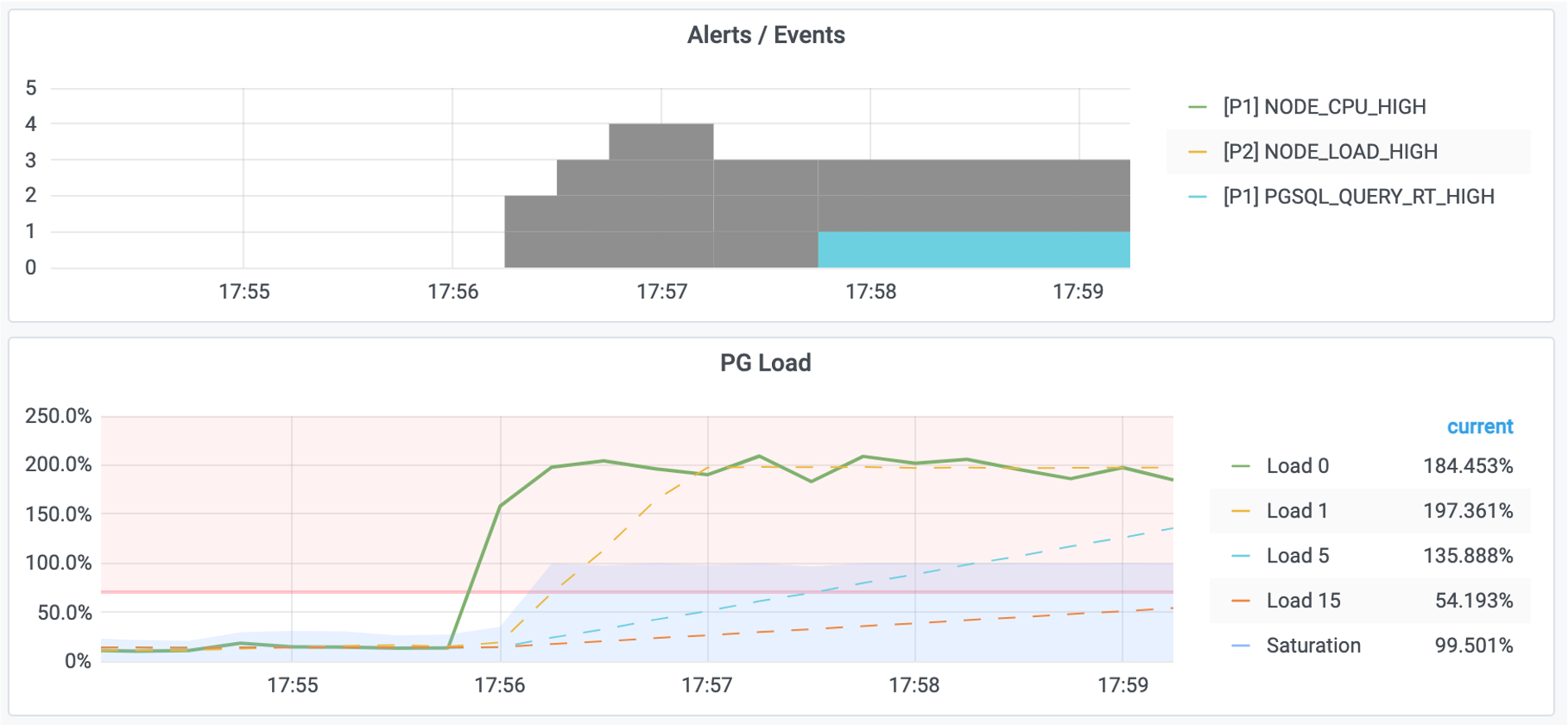

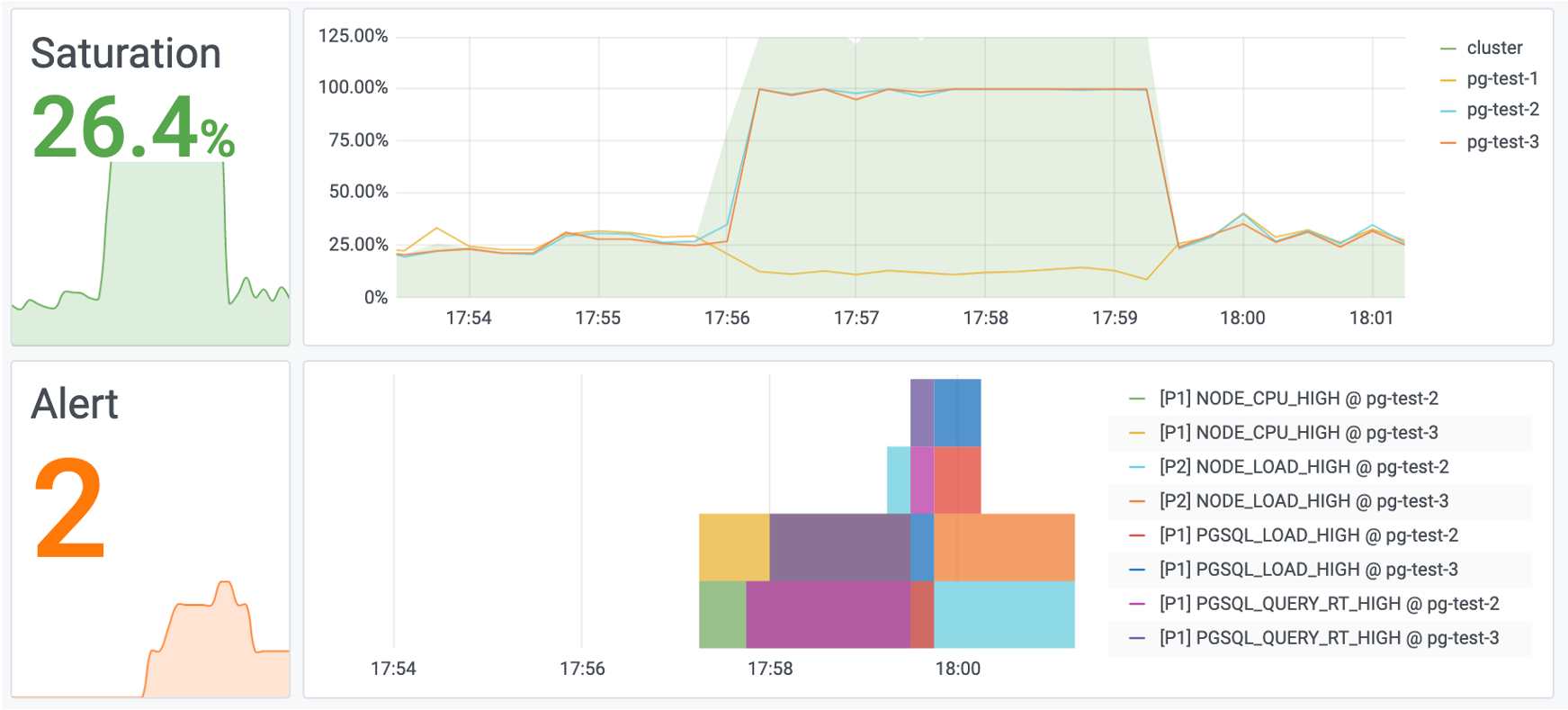

The second incident was more interesting: extremely high CPU usage triggered a bug where the WALSender process kept spin-looping instead of sending WAL to replicas, even after CPU levels returned to normal. This led to increased replication lag.

Feature Suggestions

Finally, Bohan raised some questions and feature suggestions to the PostgreSQL developer community:

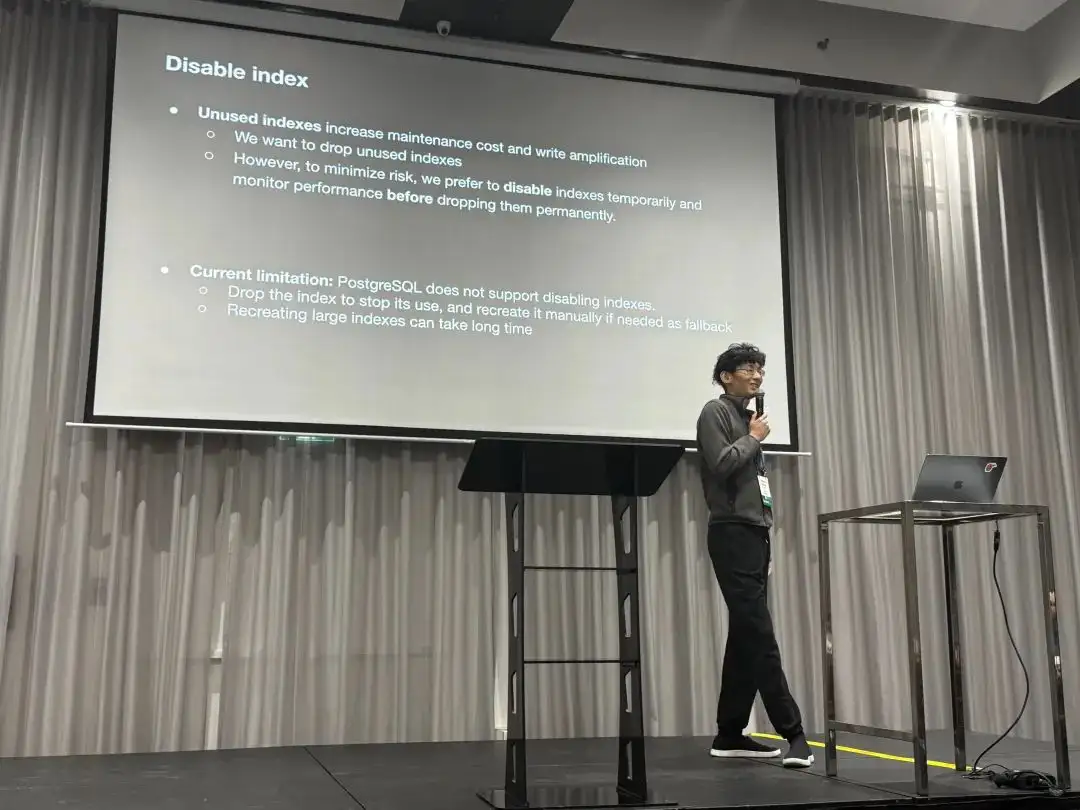

First, regarding disabling indexes. Unused indexes cause write amplification and extra maintenance overhead. They want to remove useless indexes, but to minimize risk, they wish for a feature to “disable” an index. This would allow them to monitor performance metrics to ensure everything is fine before actually dropping it.

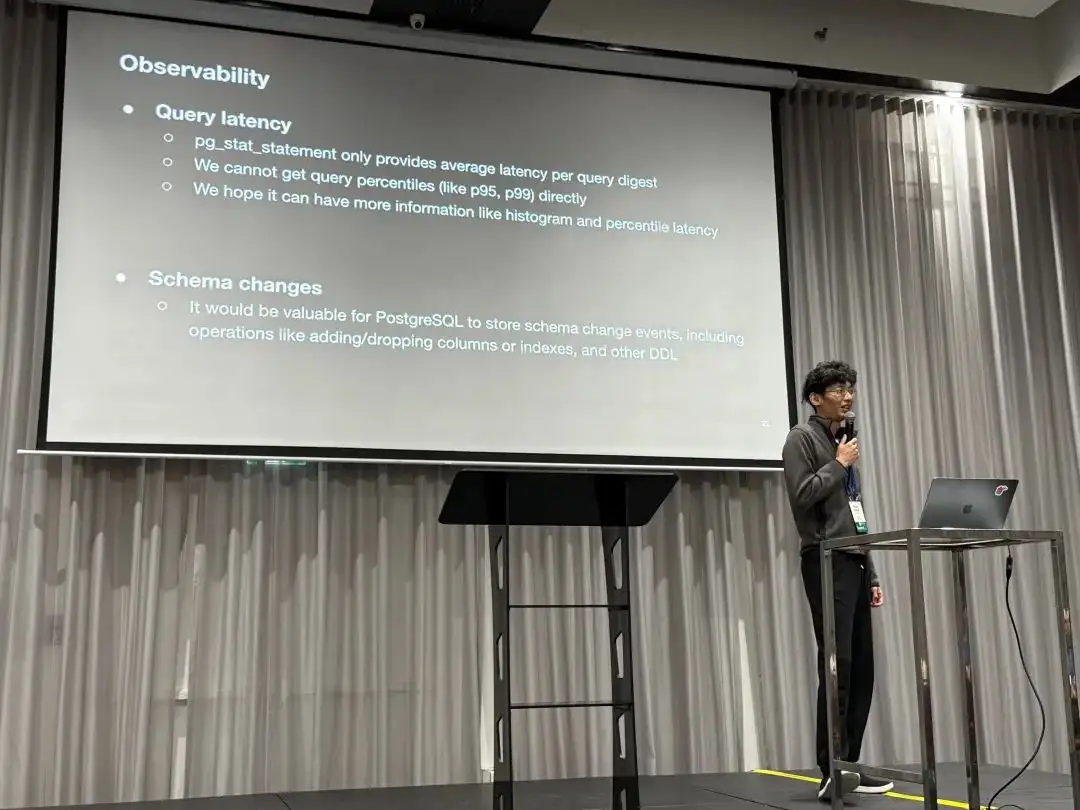

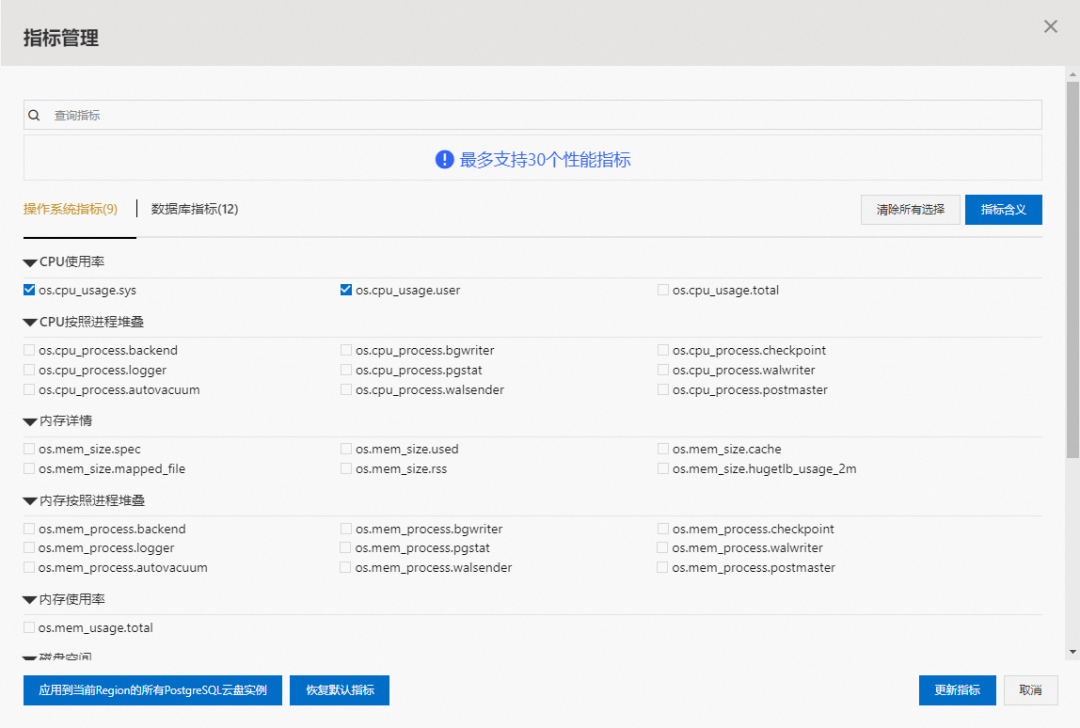

Second is about RT observability. Currently, pg_stat_statement only provides the average response time for each query type, but doesn’t directly offer latency metrics like p95 or p99. They hope for more histogram-like and percentile latency metrics.

The third point is about schema changes. They want PostgreSQL to record a history of schema change events, such as adding/removing columns and other DDL operations.

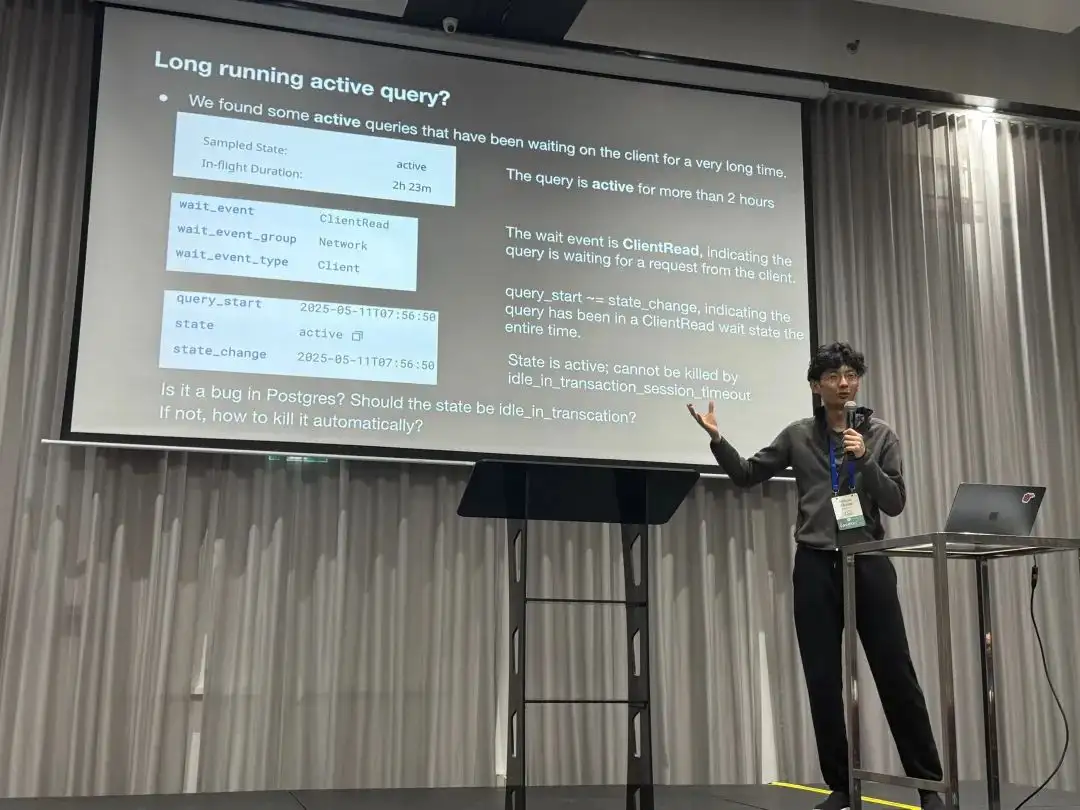

The fourth case is about the semantics of monitoring views. They found a session with state = 'active' and wait_event = 'ClientRead' that lasted for over two hours. This means a connection remained active long after query_start, and such connections can’t be killed by the idle_in_transaction_timeout. They wanted to know if this is a bug and how to resolve it.

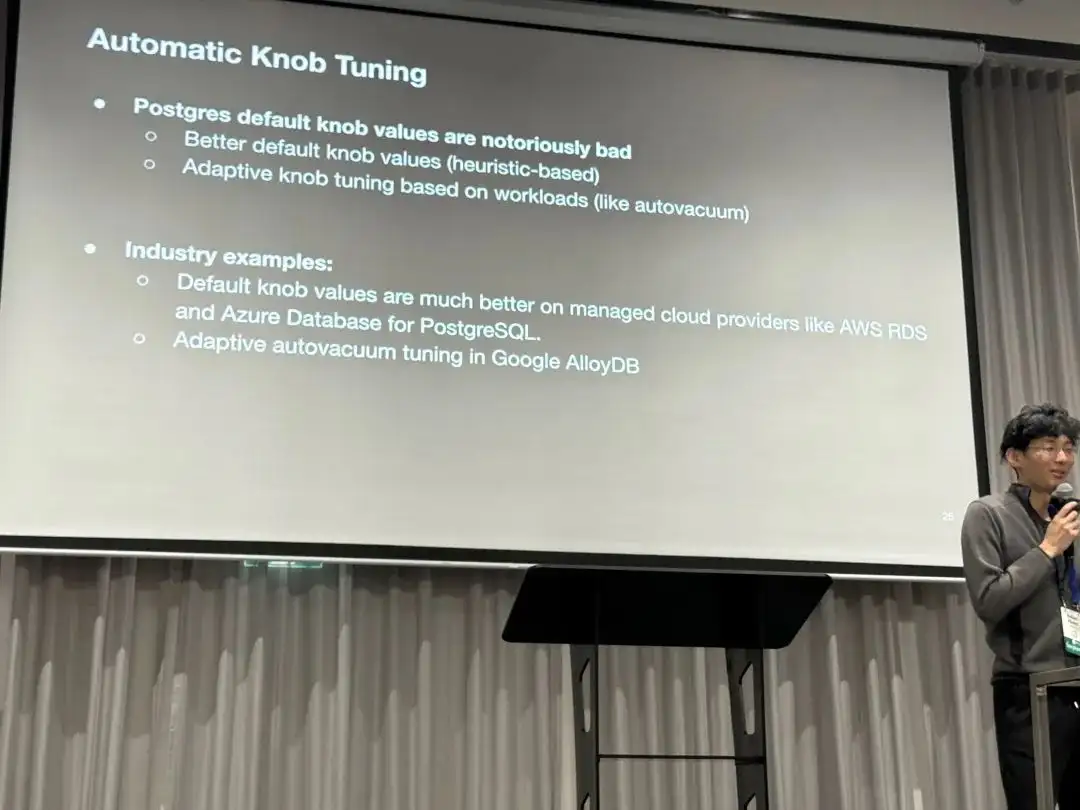

Finally, a suggestion for optimizing PostgreSQL’s default parameters. The default values are too conservative. Could better defaults be used, or perhaps a heuristic-based configuration rule?

Vonng’s Commentary

Although PGConf.Dev 2025 is primarily focused on development, you often see use case presentations from users, like this one from OpenAI on their PostgreSQL scaling practices. These topics are actually quite interesting for core developers, as many of them don’t have a clear picture of how PostgreSQL is used in extreme scenarios, and these talks are very helpful.

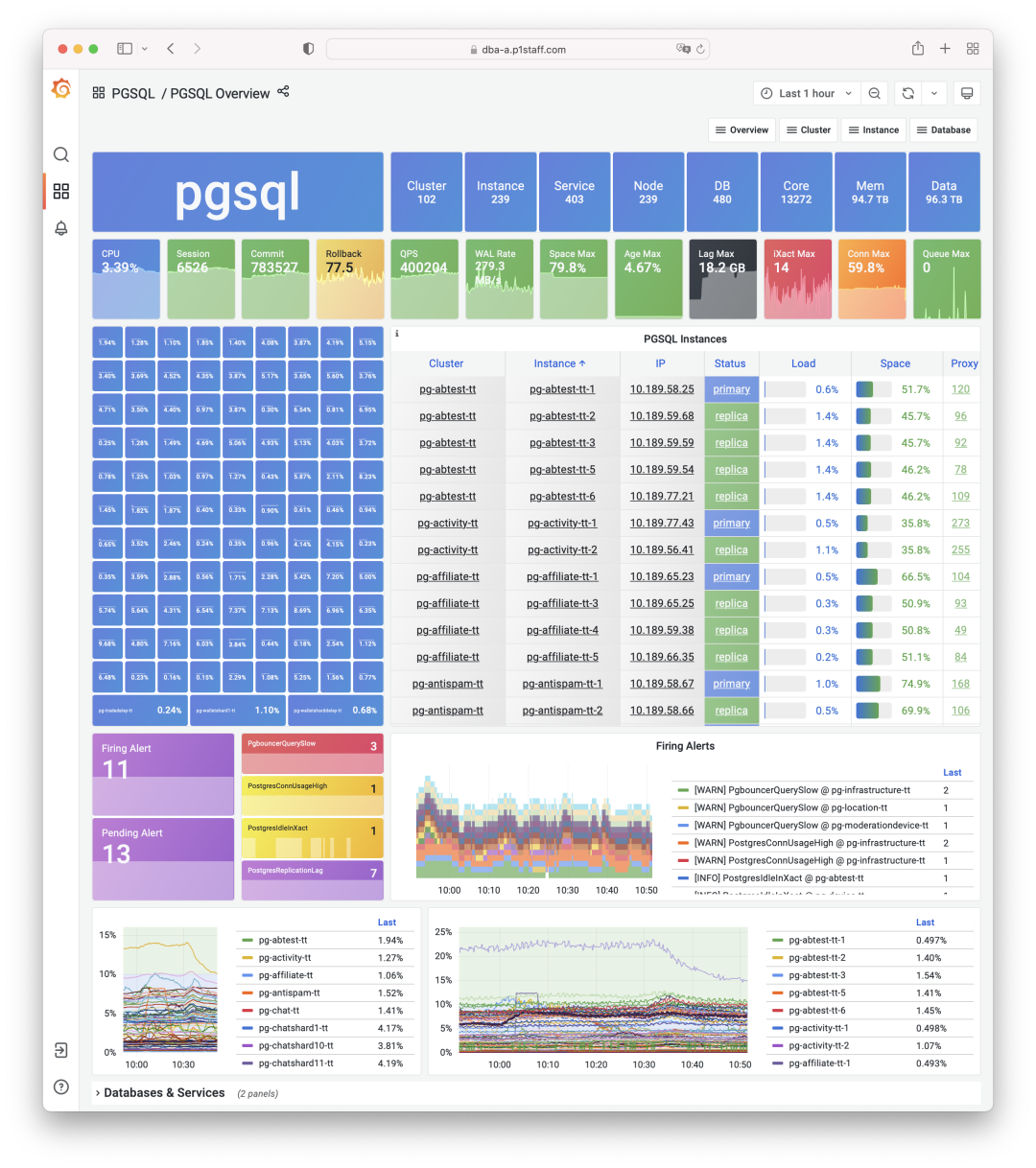

Since late 2017, I managed dozens of PostgreSQL clusters at Tantan, which was one of the largest and most complex PG deployments in the Chinese internet scene: dozens of PG clusters with around 2.5 million QPS. Back then, our largest core primary had a 1-primary-33-replica setup, with a single cluster handling around 400K QPS. The bottleneck was also on single-database writes, which we eventually solved with application-side sharding, similar to Instagram’s approach.

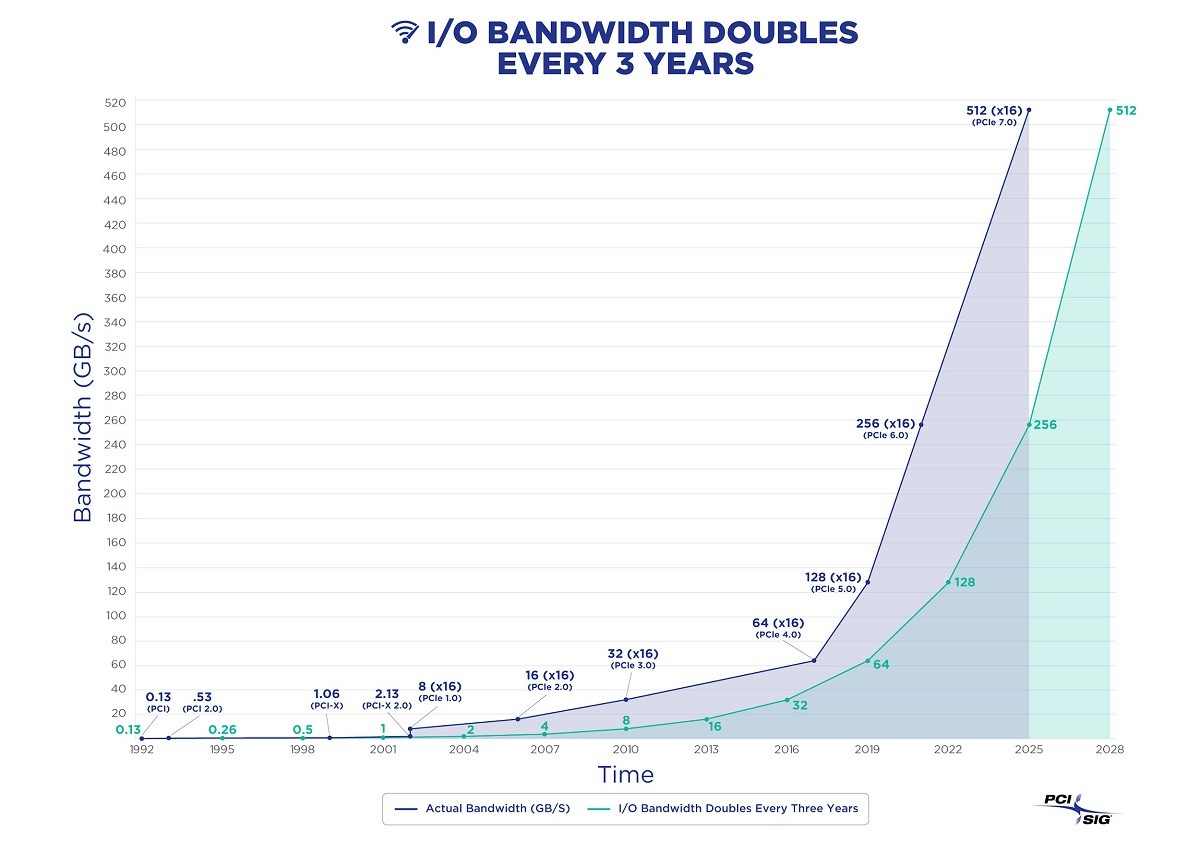

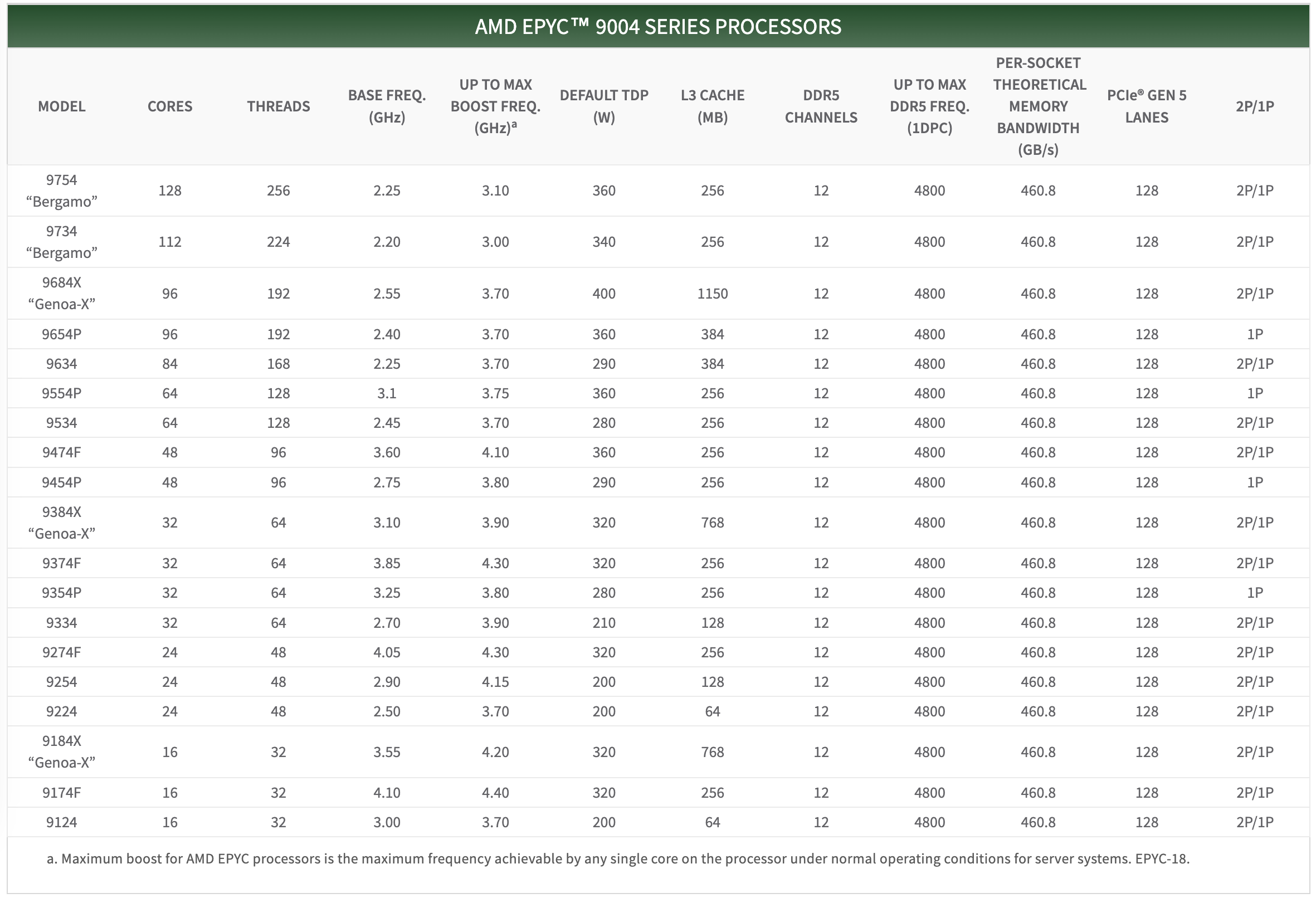

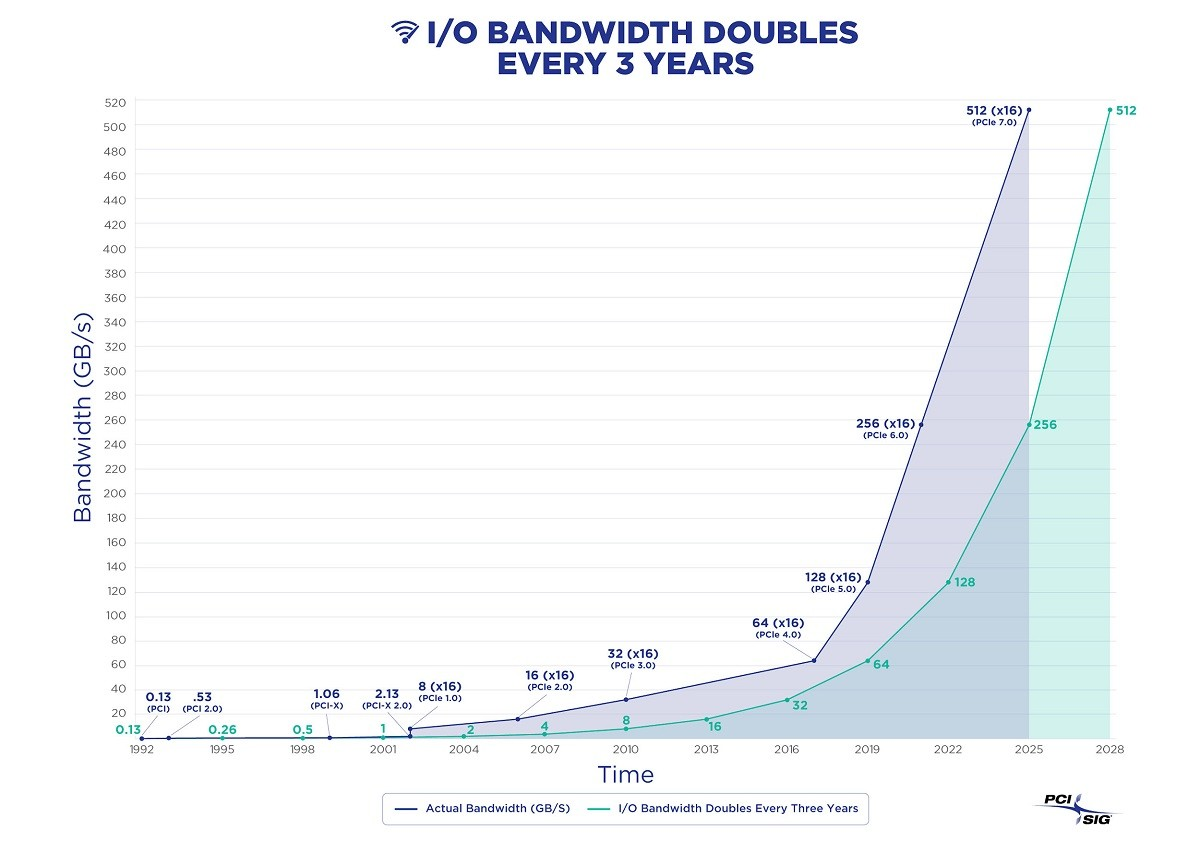

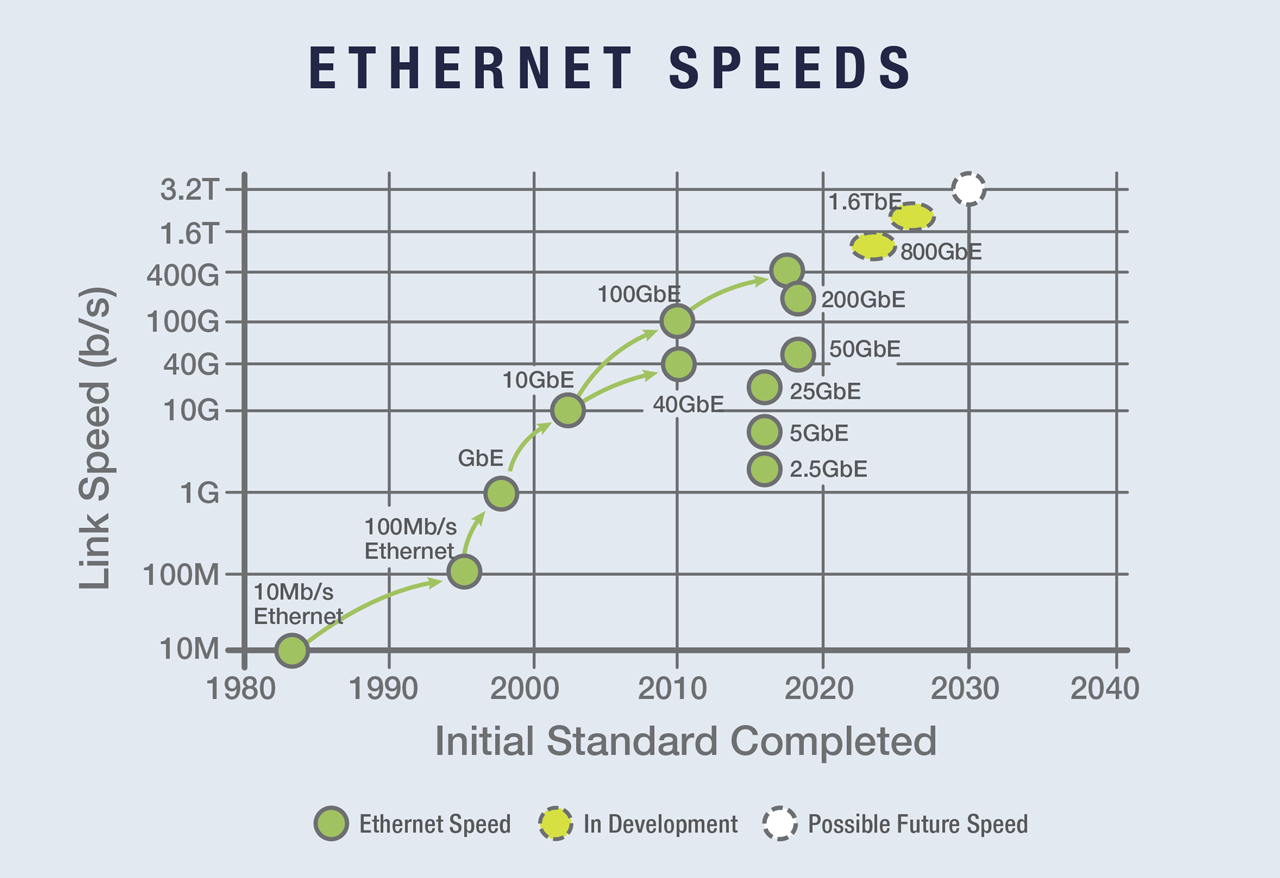

You could say I’ve encountered all the problems and used all the solutions OpenAI mentioned in their talk. Of course, the difference is that today’s top-tier hardware is orders of magnitude better than it was eight years ago. This allows a startup like OpenAI to serve its entire business with a single PostgreSQL cluster without sharding. This is undoubtedly another powerful piece of evidence for the argument that “Distributed Databases Are a False Need”.

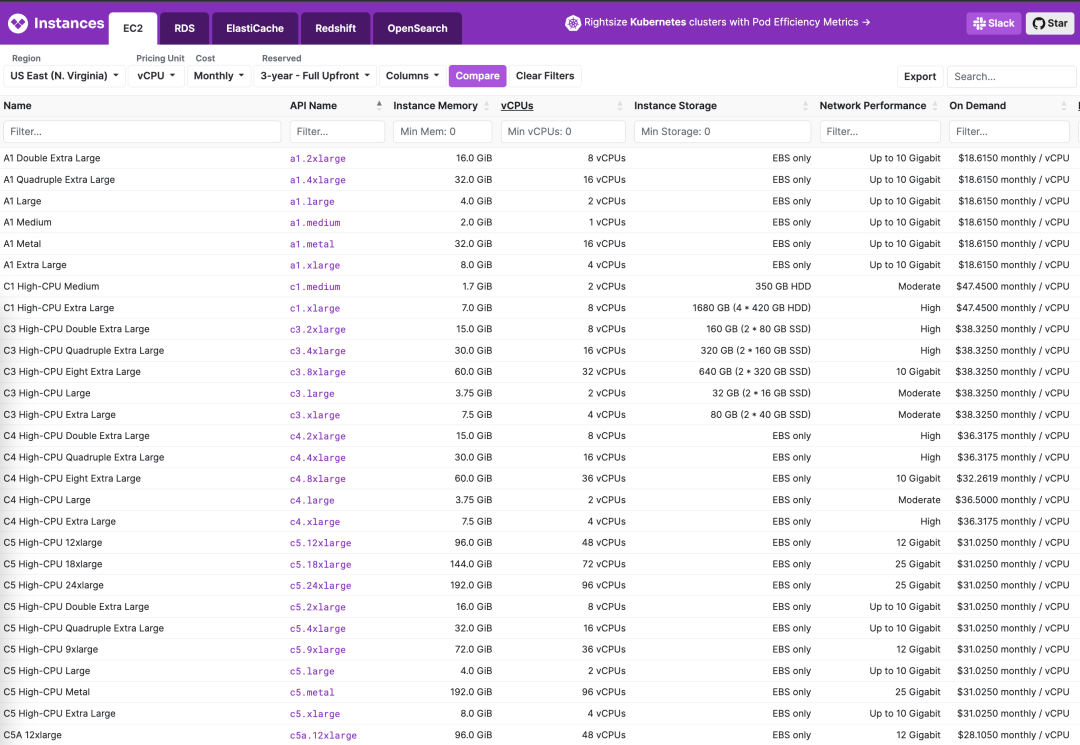

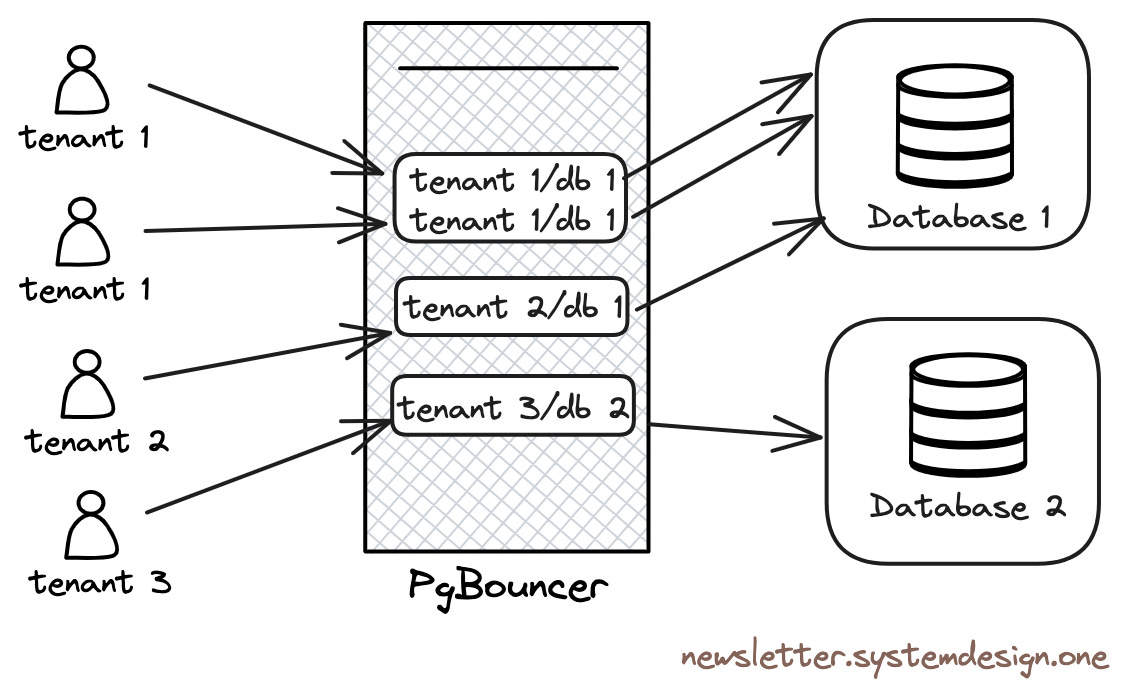

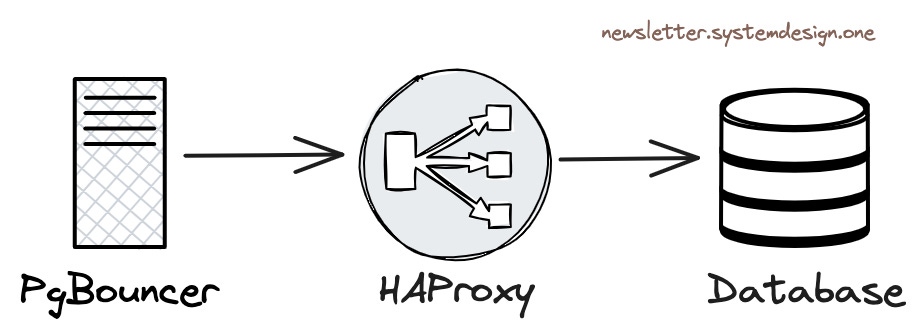

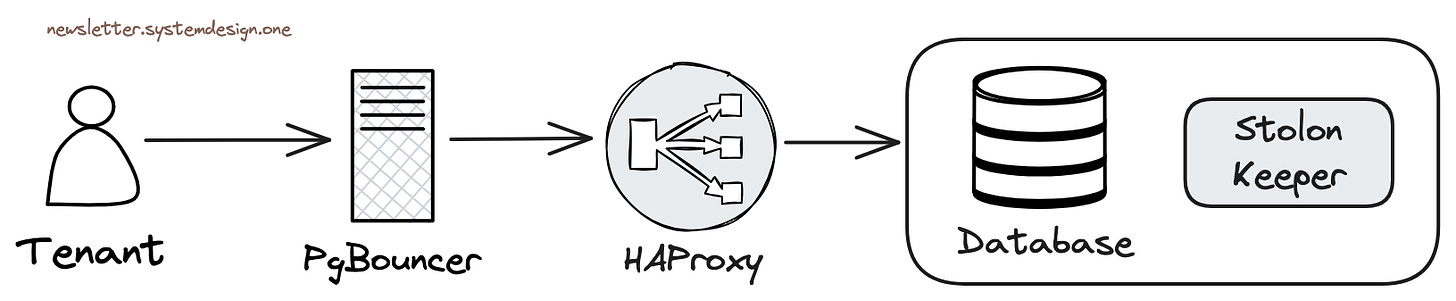

During the Q&A, I learned that OpenAI uses managed PostgreSQL on Azure with the highest available server hardware specs. They have dozens of replicas, including some in different geographical regions, and this behemoth cluster handles a total of about millions QPS. They use Datadog for monitoring, and the services access the RDS cluster from Kubernetes through a business-side PgBouncer connection pool.

As a strategic customer, the Azure PostgreSQL team provides them with dedicated support. But it’s clear that even with top-tier cloud database services, the customer needs to have sufficient knowledge and skill on the application and operations side. Even with the brainpower of OpenAI, they still stumble on some of the practical driving lessons of PostgreSQL.

During the social event after the conference, I had a great chat with Bohan and two other database founders until the wee hours. The off-the-record discussions were fascinating, but I can’t disclose more here, haha.

Vonng’s Q&A

Regarding the questions and feature requests Bohan raised, I can offer some answers here.

Most of the features OpenAI wants already exist in the PostgreSQL ecosystem, they just might not be available in the vanilla PG kernel or in a managed cloud database environment.

On Disabling Indexes

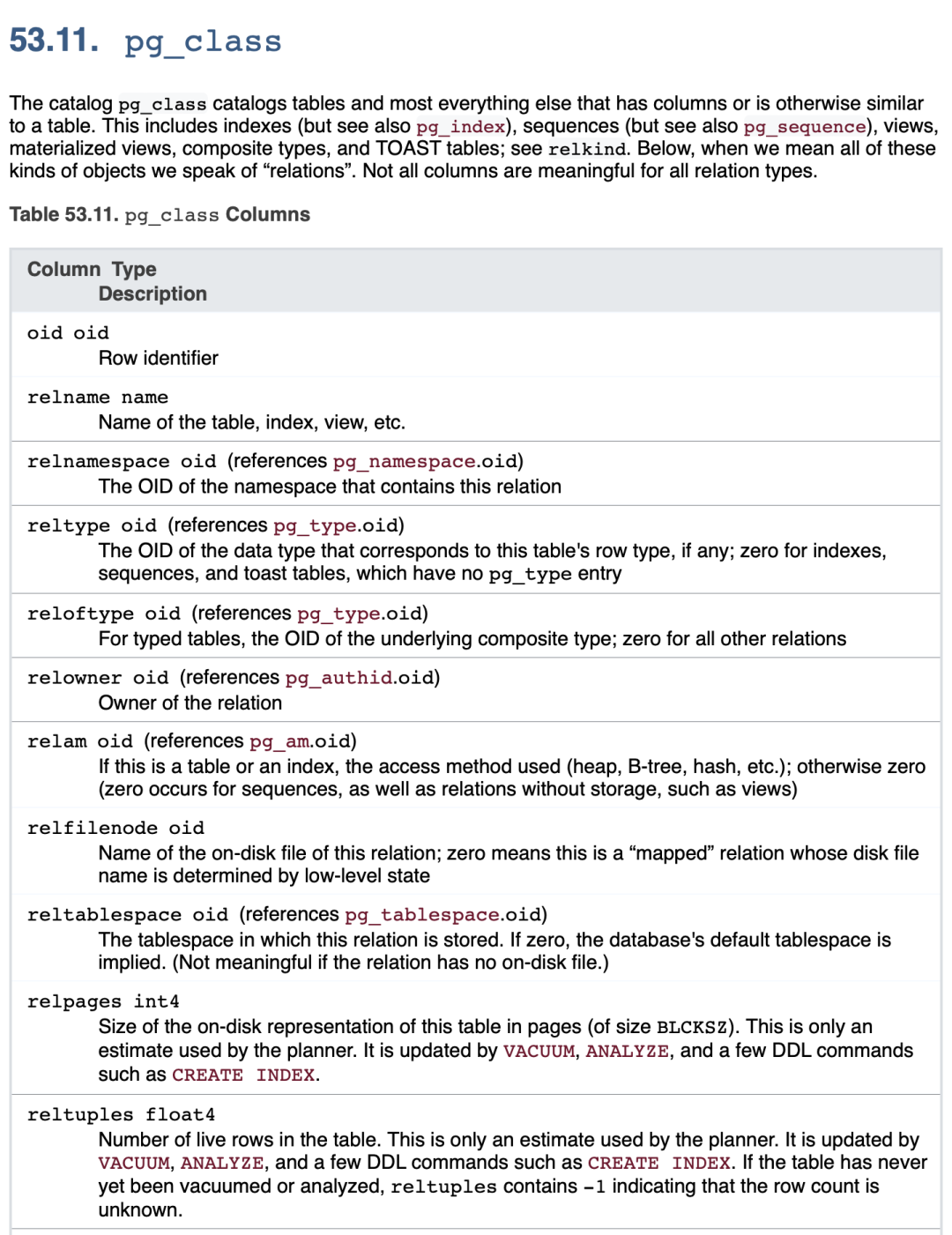

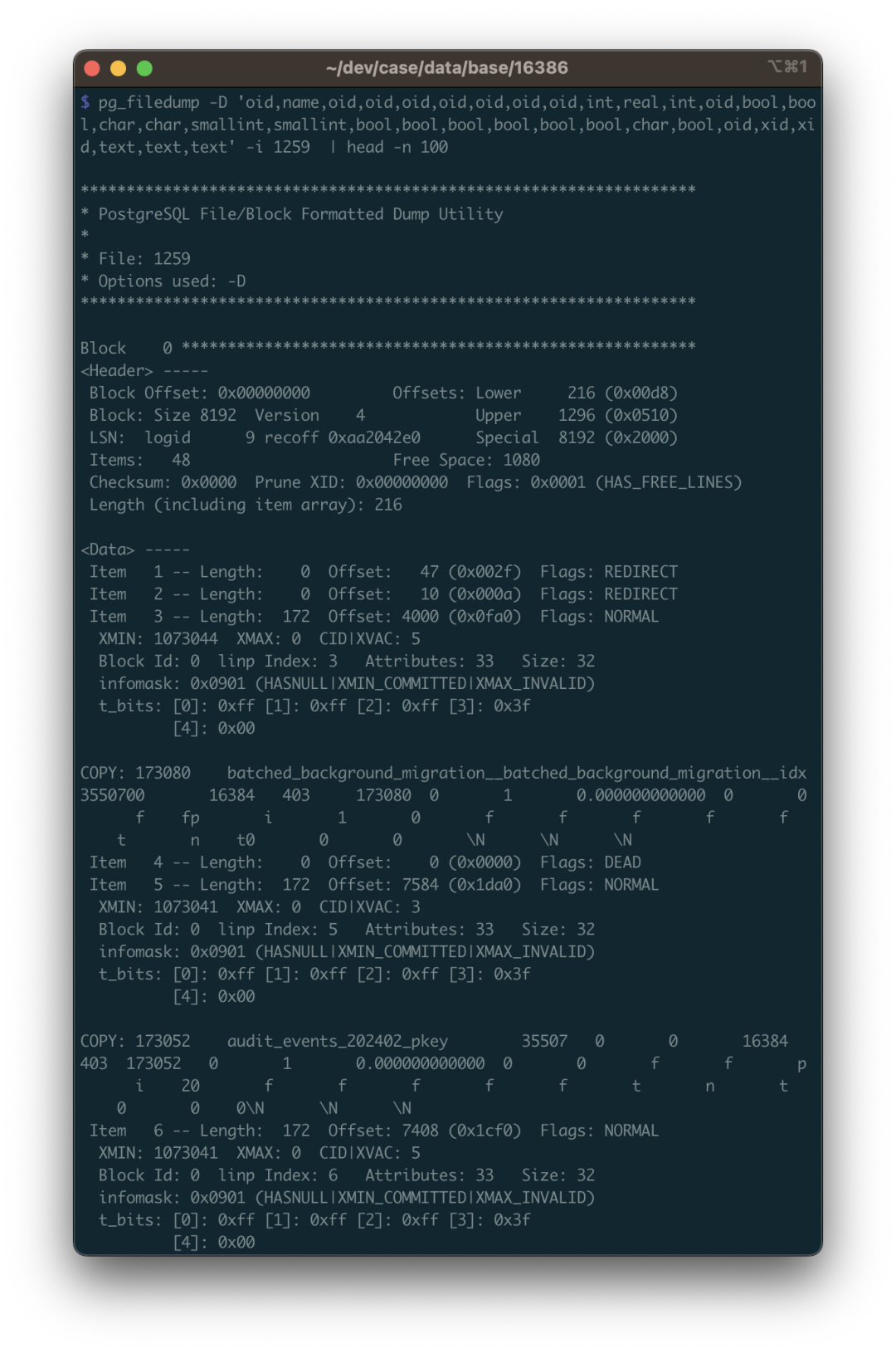

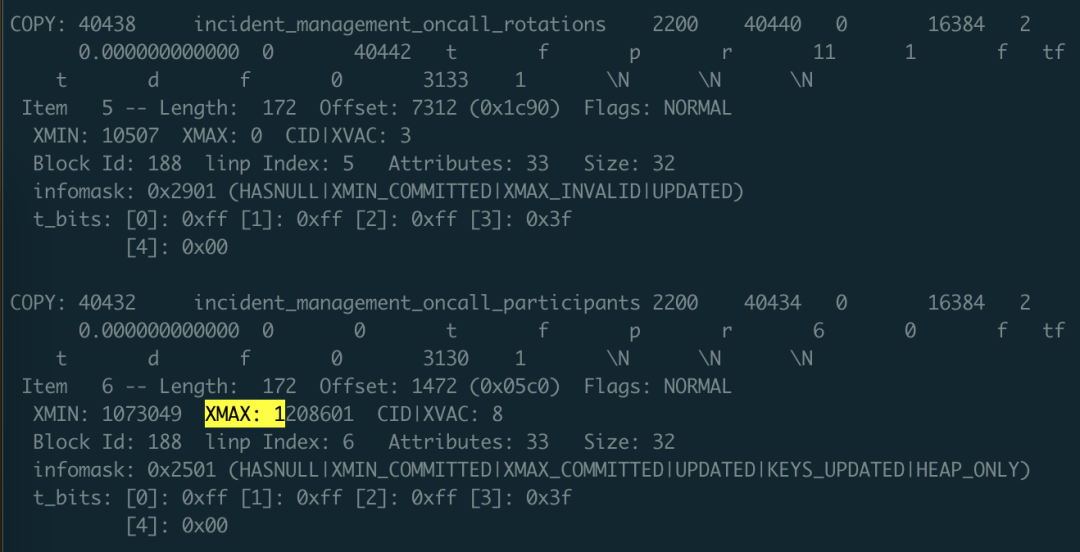

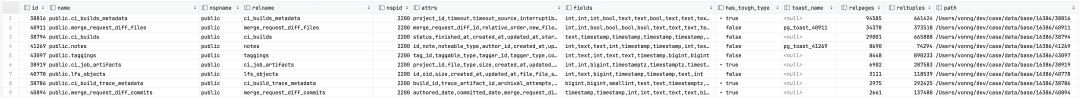

PostgreSQL actually has a “feature” to disable indexes. You just need to update the indisvalid field in the pg_index system catalog to false.

The planner will then stop using the index, but it will continue to be maintained during DML operations. In principle, there’s nothing wrong with this, as concurrent index creation uses these two flags (isready, isvalid). It’s not black magic.

However, I can understand why OpenAI can’t use this method: it’s an undocumented “internal detail” rather than a formal feature. But more importantly, cloud databases usually don’t grant superuser privileges, so you just can’t update the system catalog like this.

But back to the original need — fear of accidentally deleting an index.

There’s a simpler solution: just confirm from monitoring view (pg_stat_all_indexes) that the index isn’t being used on either the primary or the replicas.

If you know an index hasn’t been used for a long time, you can safely delete it.

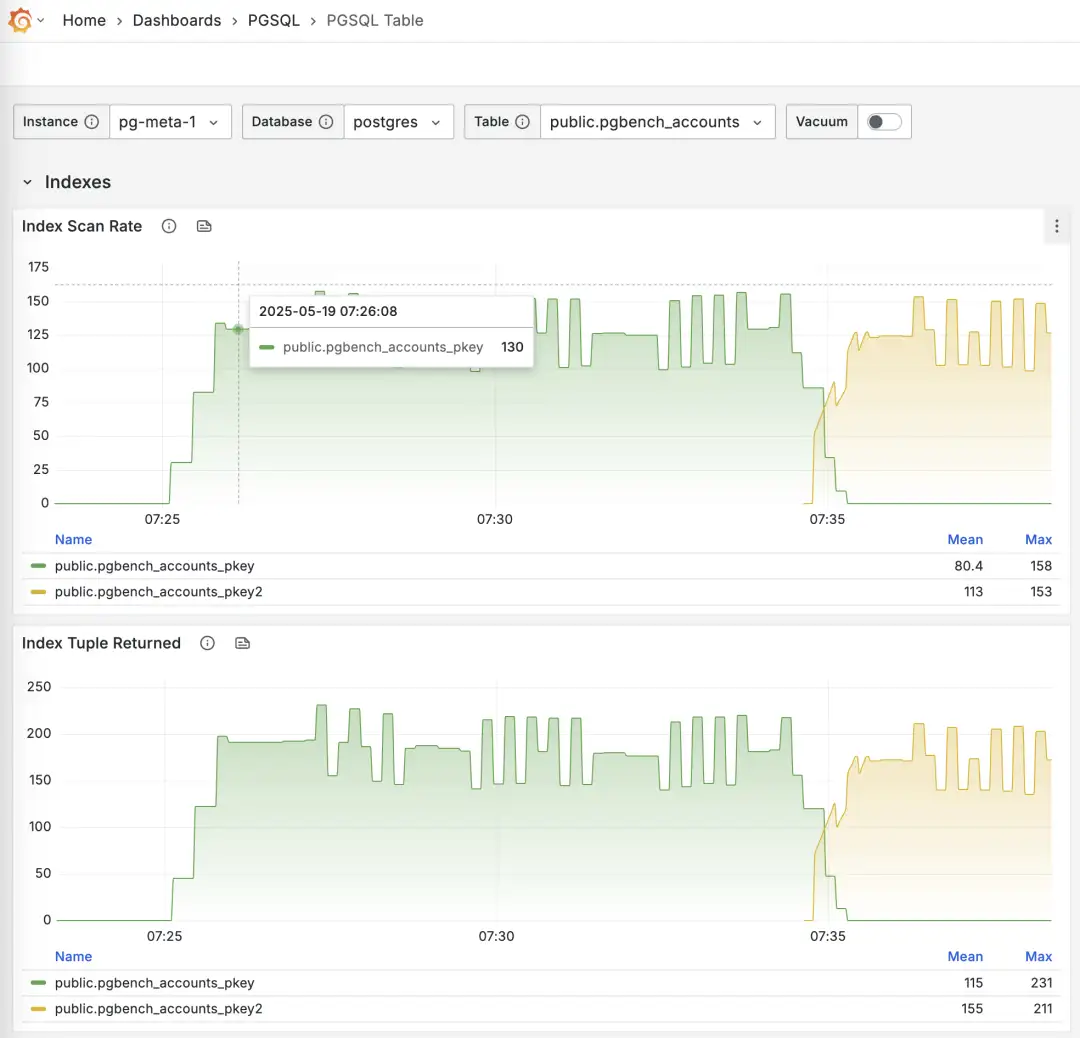

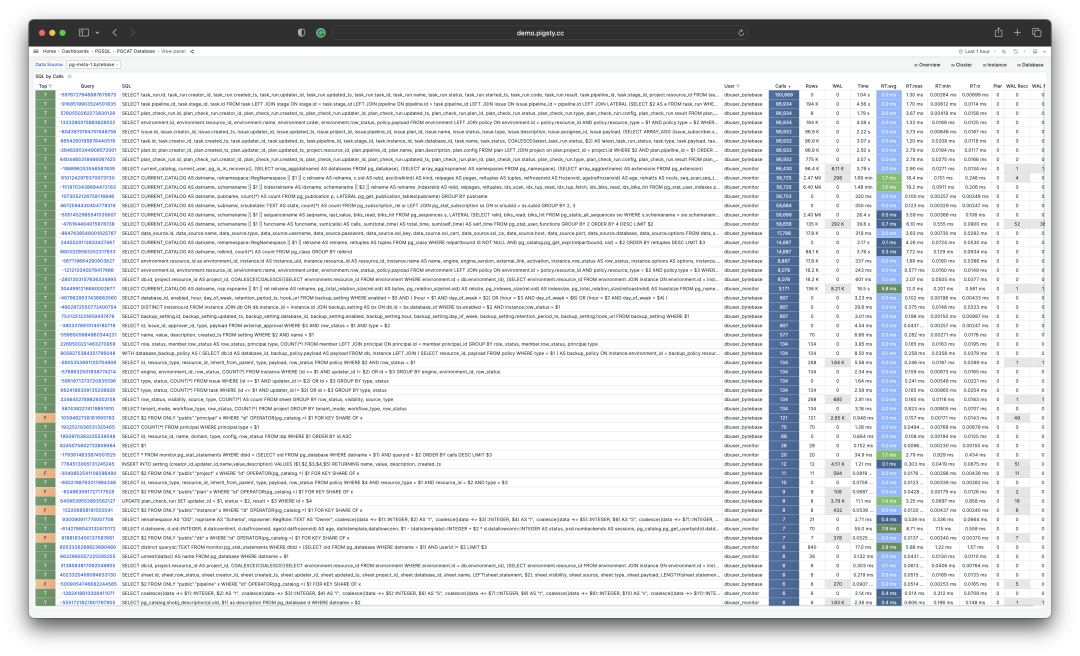

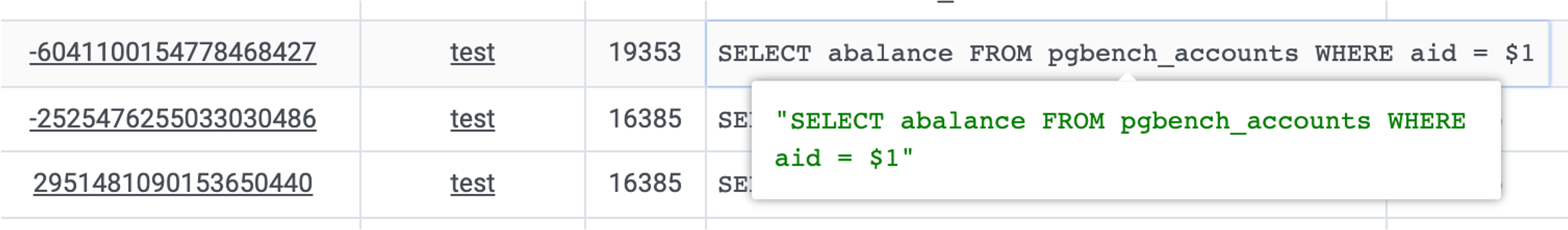

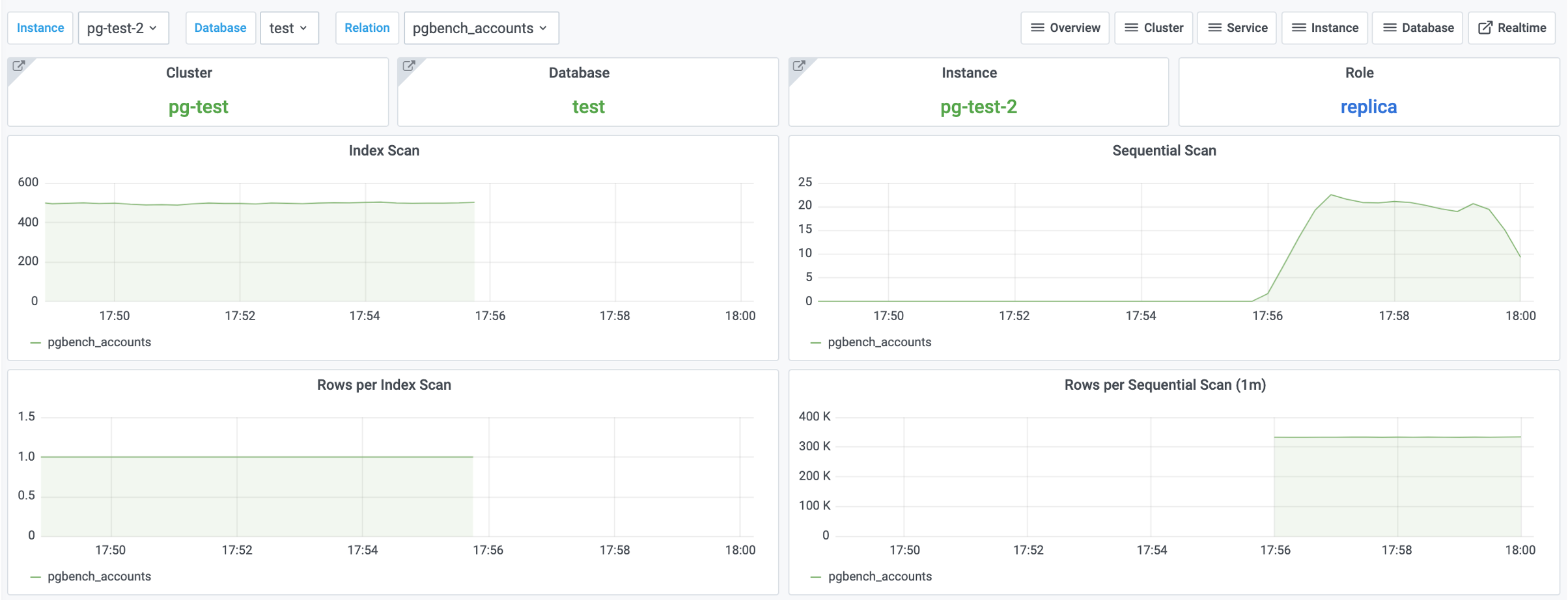

Monitoring index switch with Pigsty PGSQL TABLES Dashboard

-- Create a new index

CREATE UNIQUE INDEX CONCURRENTLY pgbench_accounts_pkey2 ON pgbench_accounts USING BTREE(aid);

-- Mark the original index as invalid (not used), but still maintained. planner will not use it.

UPDATE pg_index SET indisvalid = false WHERE indexrelid = 'pgbench_accounts_pkey'::regclass;

On Observability

Actually, pg_stat_statements provides the mean and stddev metrics, which you can use with properties of the normal distribution to estimate percentile metrics.

But this is only a rough estimate, and you need to reset the counters periodically, otherwise the effectiveness of the full historical statistics will degrade over time.

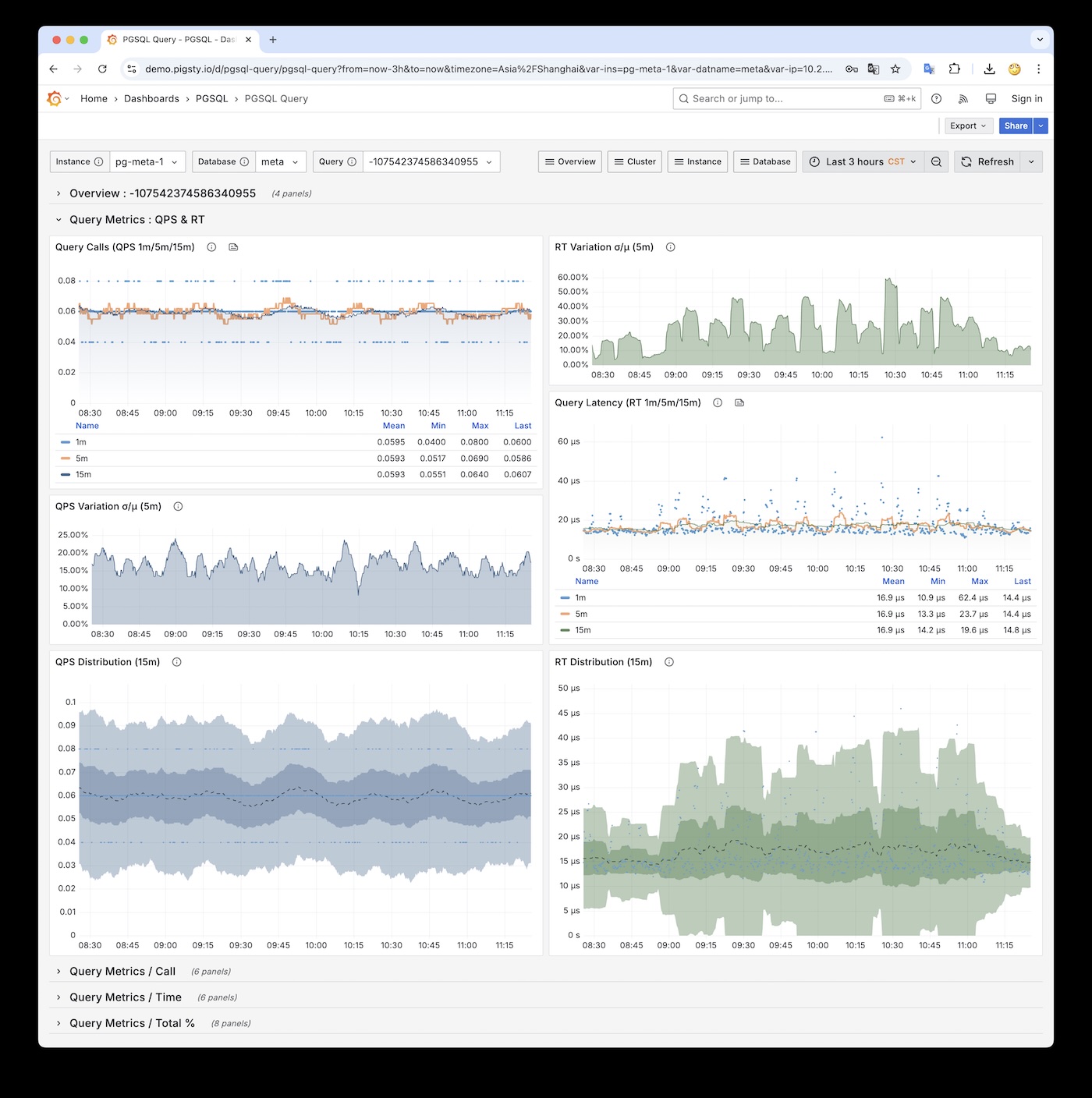

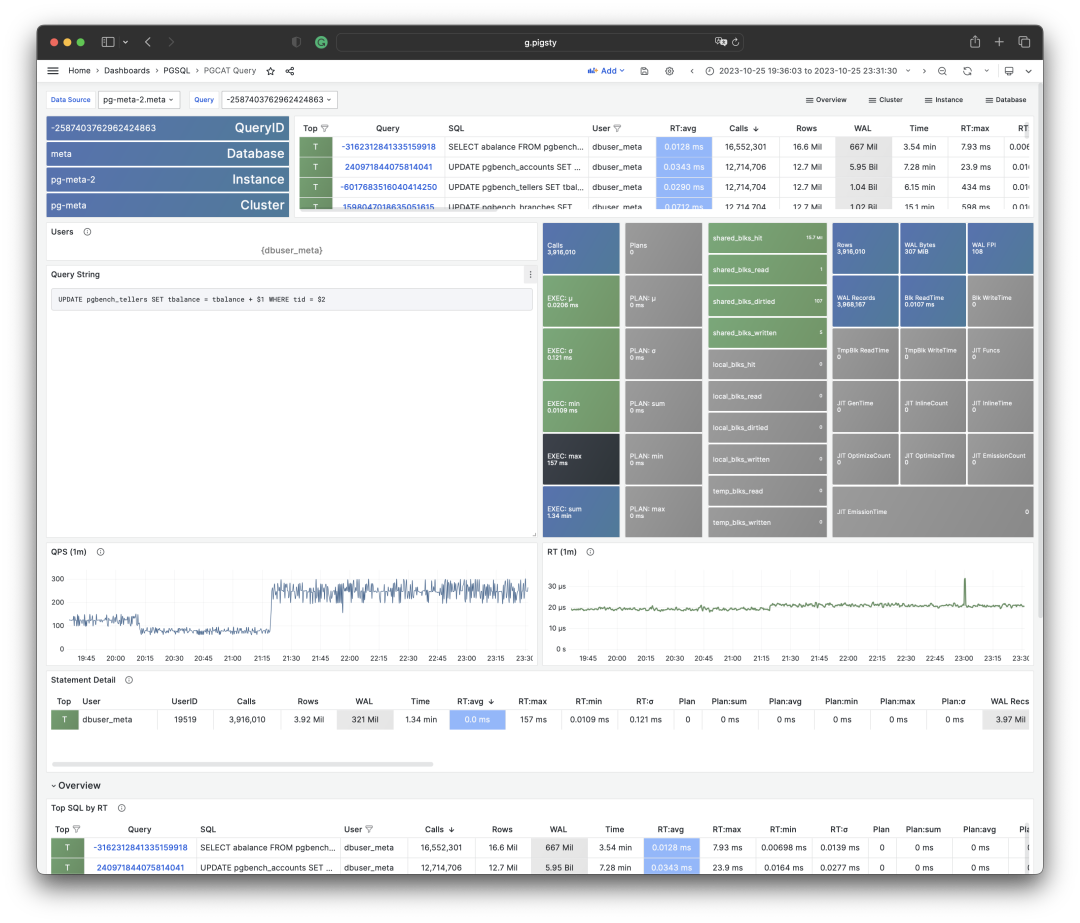

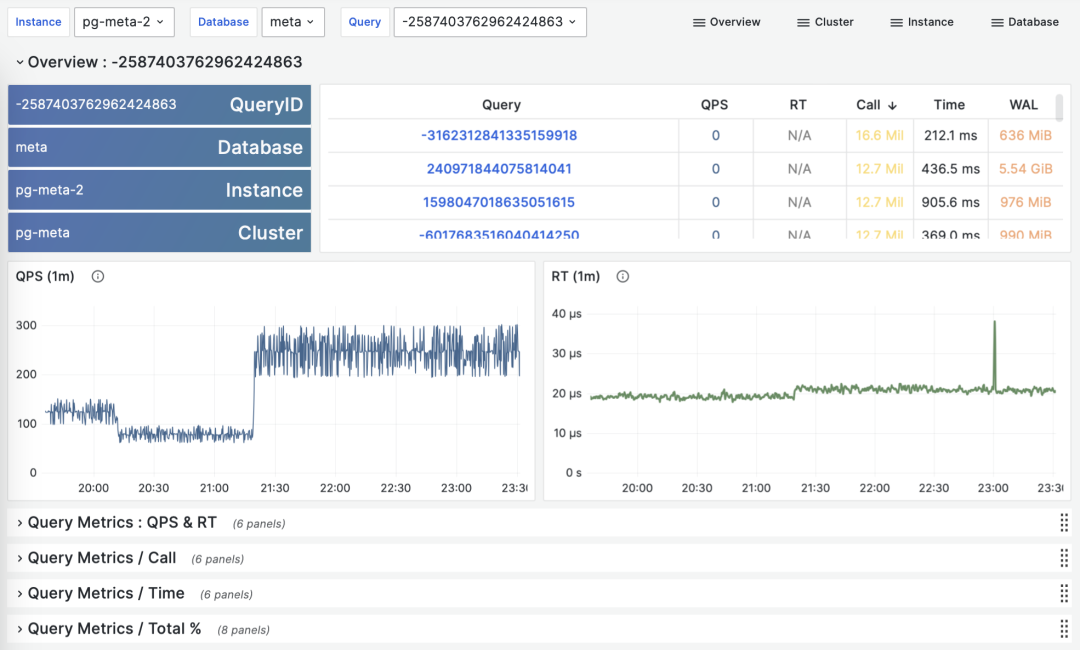

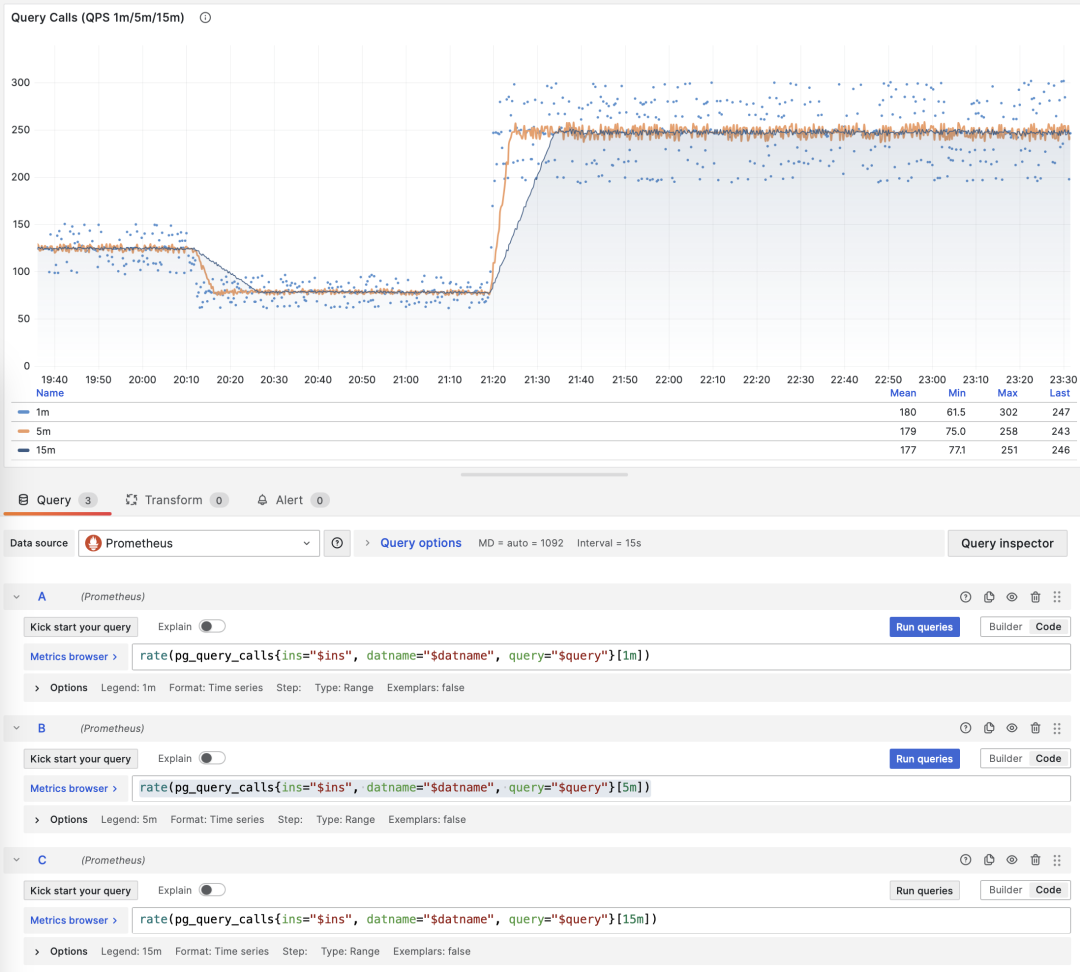

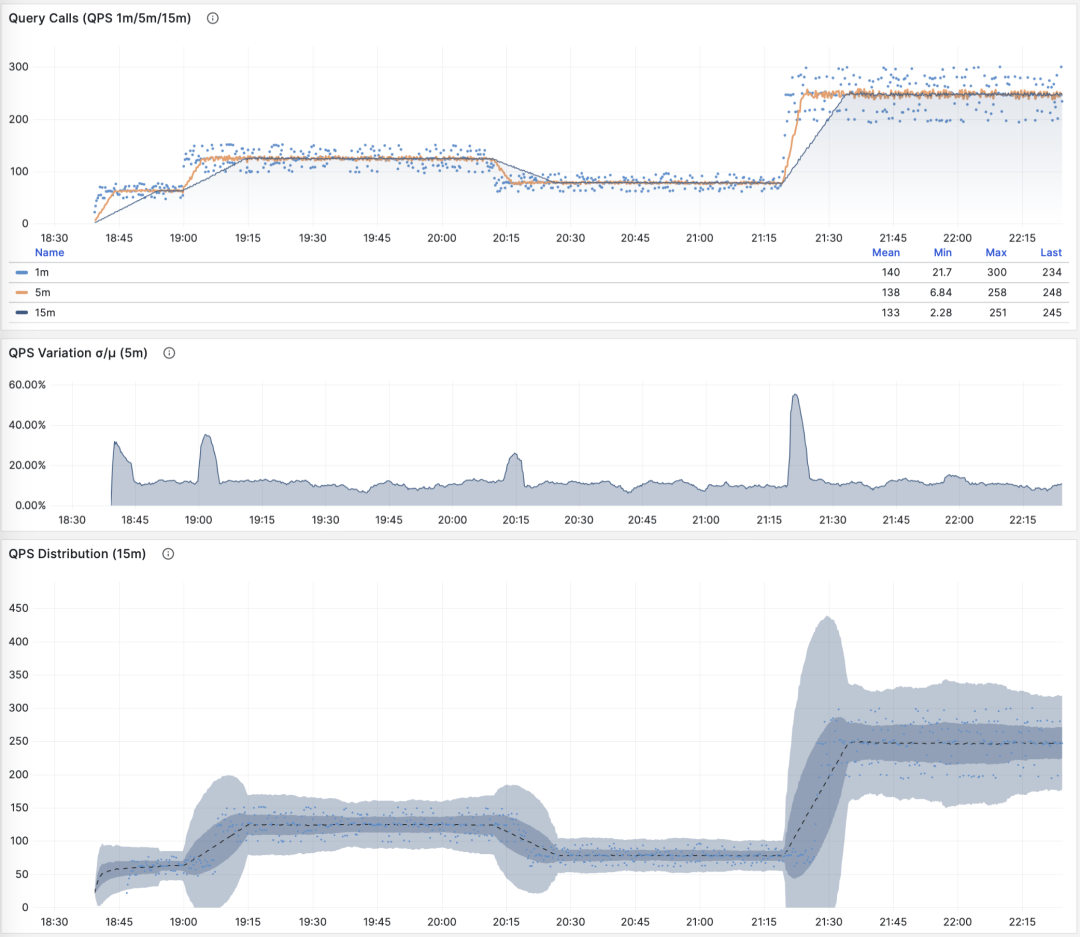

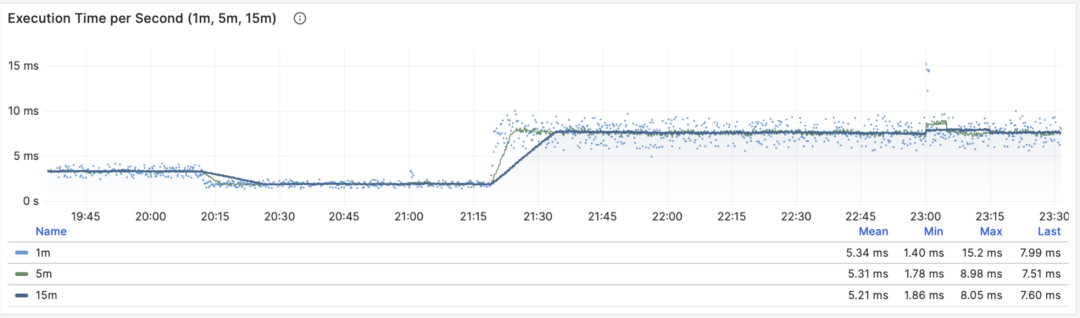

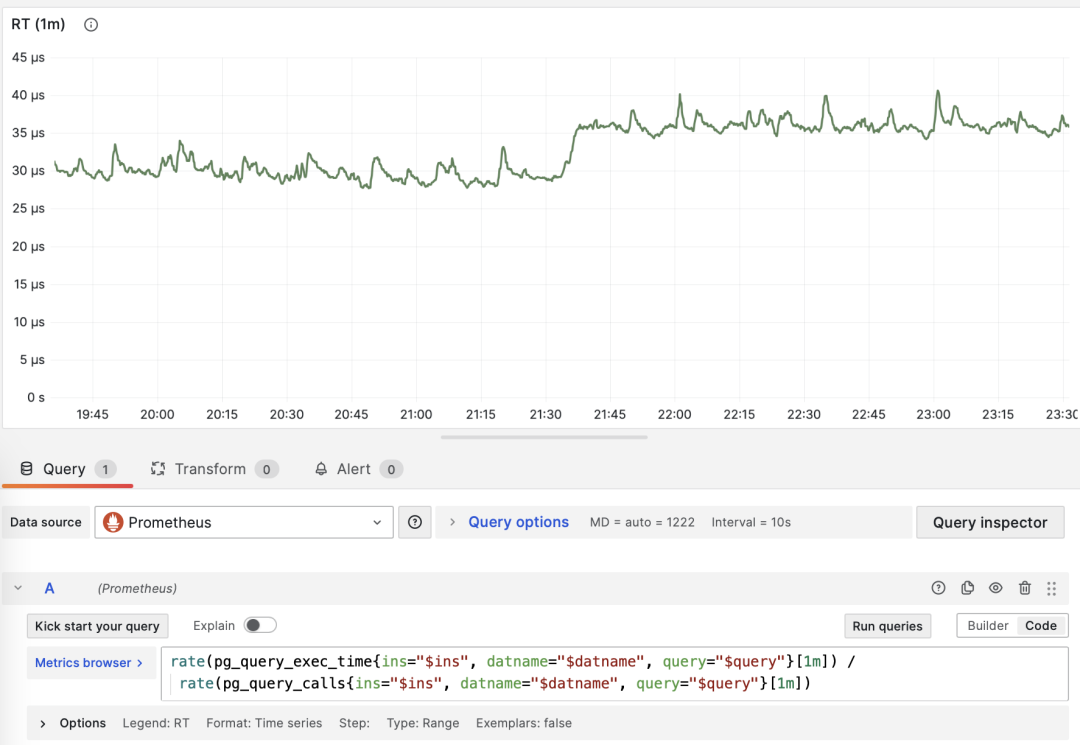

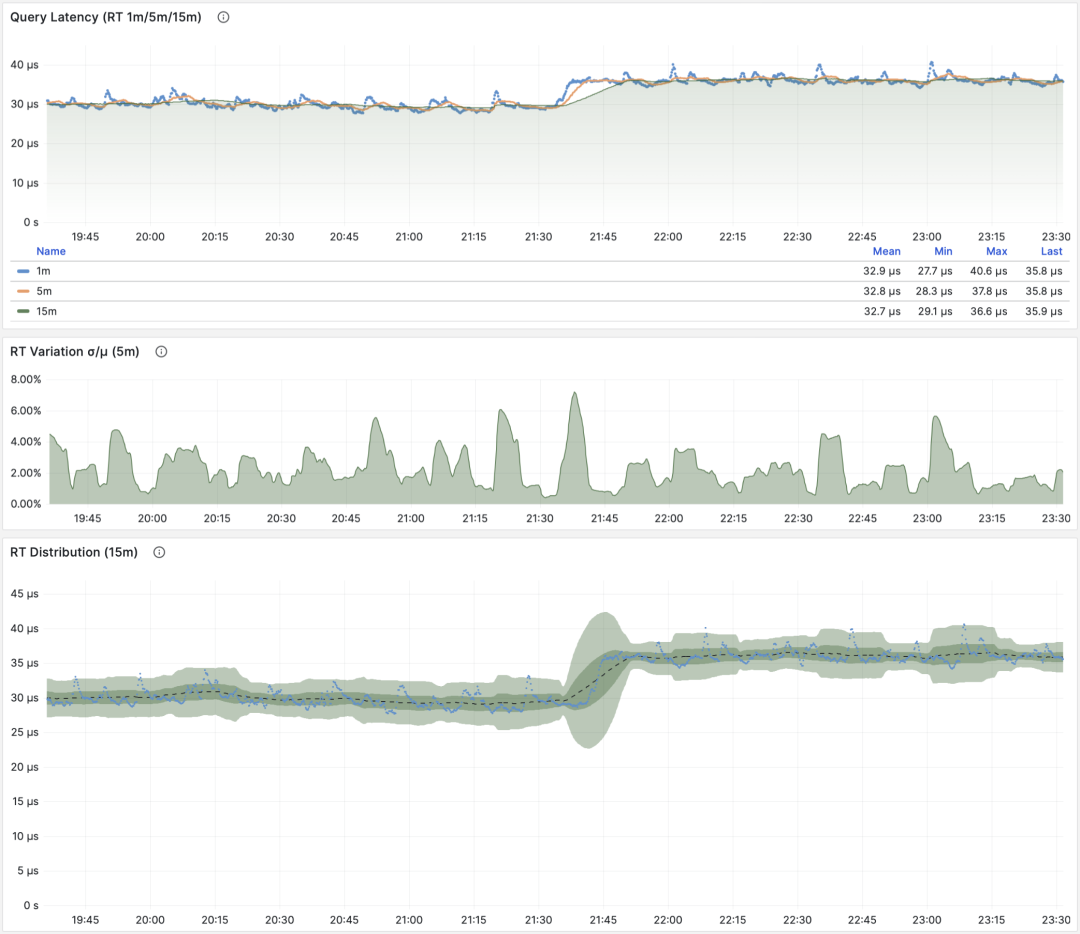

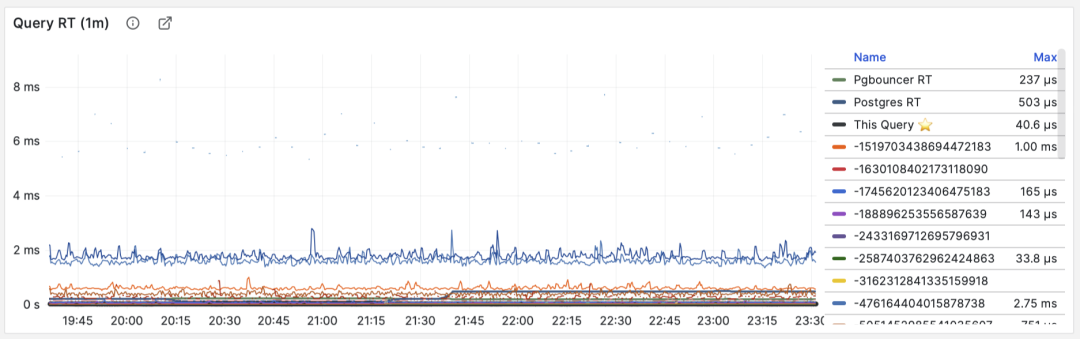

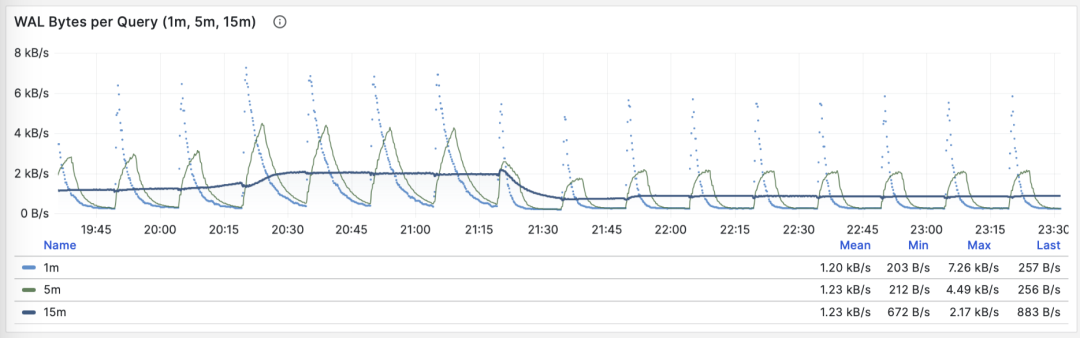

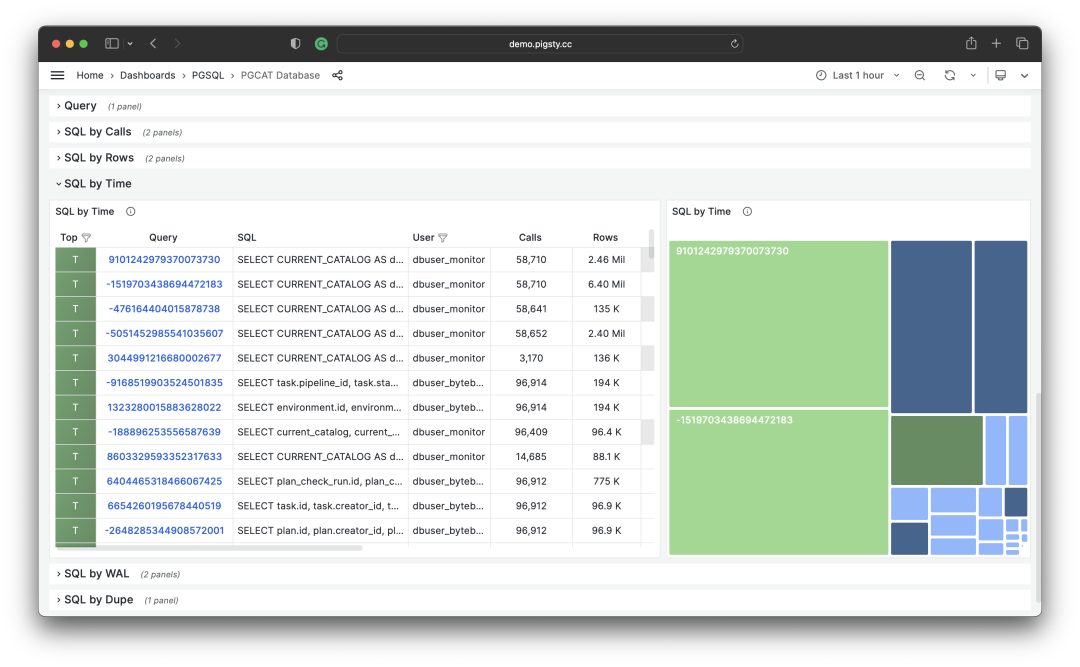

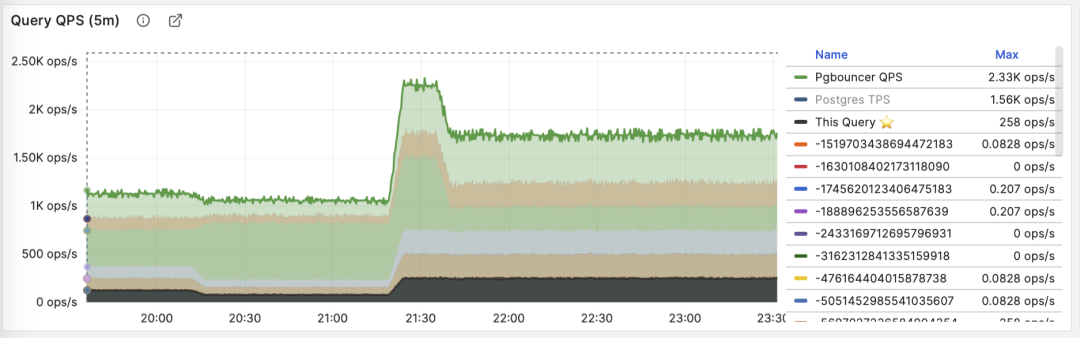

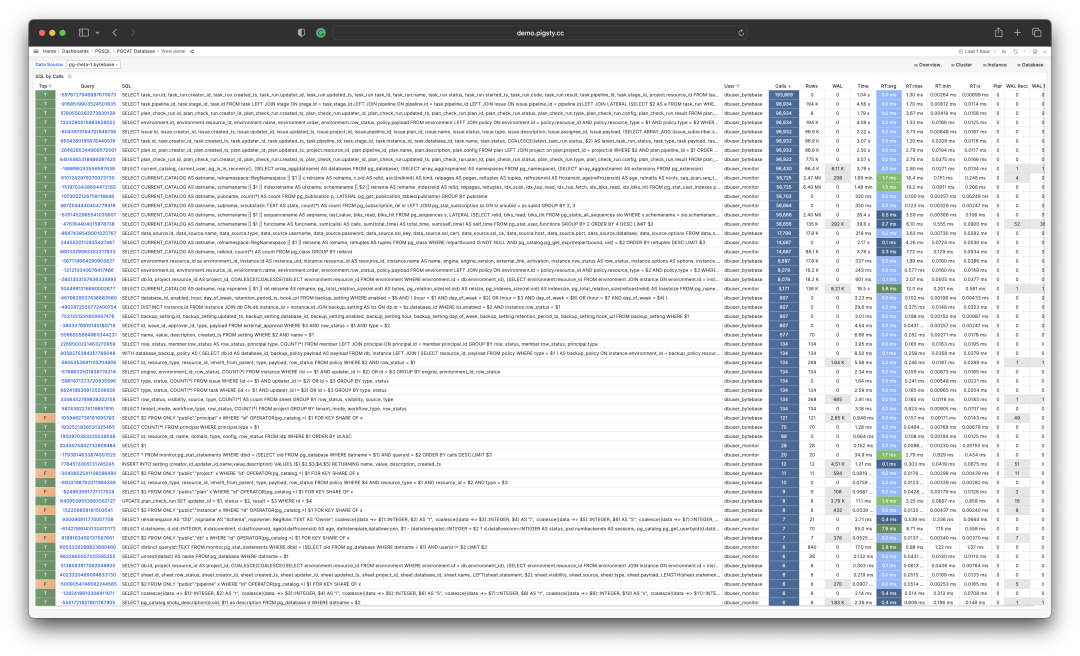

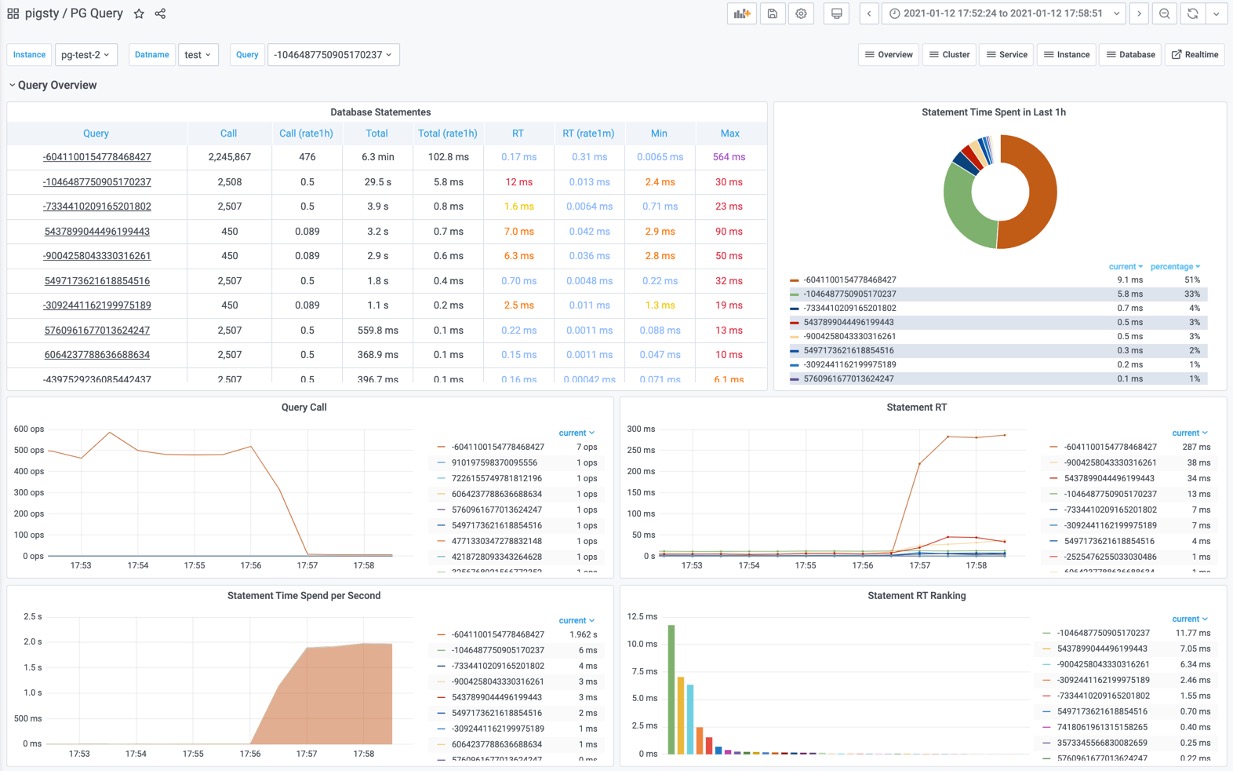

RT Distribution with PGSQL QUERY Dashboard from PGSS

PGSS is unlikely to provide P95, P99 RT percentile metrics anytime soon, because it would increase the extension’s memory footprint by several dozen times. While that’s not a big deal for modern servers, it could be an issue in extremely conservative environments. I asked the maintainer of PGSS about this at the Unconference, and it’s unlikely to happen in the short term. I also asked Jelte, the maintainer of Pgbouncer, if this could be solved at the connection pool level, and a feature like that is not coming soon either.

However, there are other solutions to this problem. First, the pg_stat_monitor extension explicitly provides detailed percentile RT metrics,

but you have to consider the performance impact of collecting these metrics on the cluster.

A universal, non-intrusive method with no database performance overhead is to add query RT monitoring directly at the application’s Data Access Layer (DAL), but this requires cooperation and effort from the application side.

Also, using eBPF for side-channel collection of RT metrics is a great idea, but considering they’re using managed PostgreSQL on Azure, they won’t have server access, so that path is likely blocked.

On Schema Change History

Actually, PostgreSQL’s logging already provides this option. You just need to set log_statement to ddl (or the more advanced mod or all),

and all DDL logs will be preserved. The pgaudit extension also provides similar functionality.

But I suspect what they really want isn’t DDL logs, but something like a system view that can be queried via SQL.

In that case, another option is CREATE EVENT TRIGGER.

You can use an event trigger to log DDL events directly into a data table.

The pg_ddl_historization extension provides a more convenient way to do this, and I’ve compiled and packaged this extension as well.

Creating an event trigger also requires superuser privileges. AWS RDS has some special handling to allow this, but it seems that PostgreSQL on Azure does not support it.

On Monitoring View Semantics

In OpenAI’s example, pg_stat_activity.state = active means the backend process is still within the lifecycle of a single SQL statement.

The WaitEvent = ClientRead means the process is on the CPU waiting for data from the client.

When both appear together, a typical example is an idle COPY FROM STDIN, but it could also be TCP blocking or being stuck between BIND / EXECUTE. So it’s hard to say if it’s a bug without knowing what the connection is actually doing.

Some might argue that waiting for client I/O should be considered “idle” from a CPU perspective. But state tracks the execution state of the statement itself, not whether the CPU is busy.

state = 'active' means the PostgreSQL backend considers “this statement is not yet finished.” Resources like row locks, buffer pins, snapshots, and file handles are considered “in use.”

This doesn’t mean it’s running on the CPU. When the process is running on the CPU in a loop waiting for client data, the wait event is ClientRead. When it yields the CPU and “waits” in the background, the wait event is NULL.

But back to the problem itself, there are other solutions. For example, in Pigsty, when accessing PostgreSQL through HAProxy, we set a connection timeout at the LB level for the primary service,

defaulting to 24 hours. More stringent environments would have a shorter timeout, like 1 hour. This means any connection lasting over an hour would be terminated.

Of course, this also needs to be configured with a corresponding max lifetime in the application-side connection pool, to proactively close connections rather than having them be cut off.

For offline, read-only services, this parameter can be omitted to allow for ultra-long queries that might run for two or three days. This provides a safety net for these active-but-waiting-on-I/O situations.

But I also doubt whether Azure PostgreSQL offers this kind of control.

On Default Parameters

PostgreSQL’s default parameters are quite conservative. For example, it defaults to using 128 MB of memory (the minimum can be set to 128 KB!). On the bright side, this allows its default configuration to run in almost any environment. On the downside, I’ve actually seen a case of a production system with 1TB of physical memory running with the 128 MB default… (thanks to double buffering, it actually ran for a long time).

But overall, I think conservative defaults aren’t a bad thing. This issue can be solved in a more flexible, dynamic configuration process.

RDS and Pigsty both provide pretty good initial parameter heuristic config rules,

which fully address this problem. But this feature could indeed be added to the PG command-line tools,

for example, having initdb automatically detect CPU/memory count, disk size, and storage type and set optimized parameter values accordingly.

Self-hosted PostgreSQL?

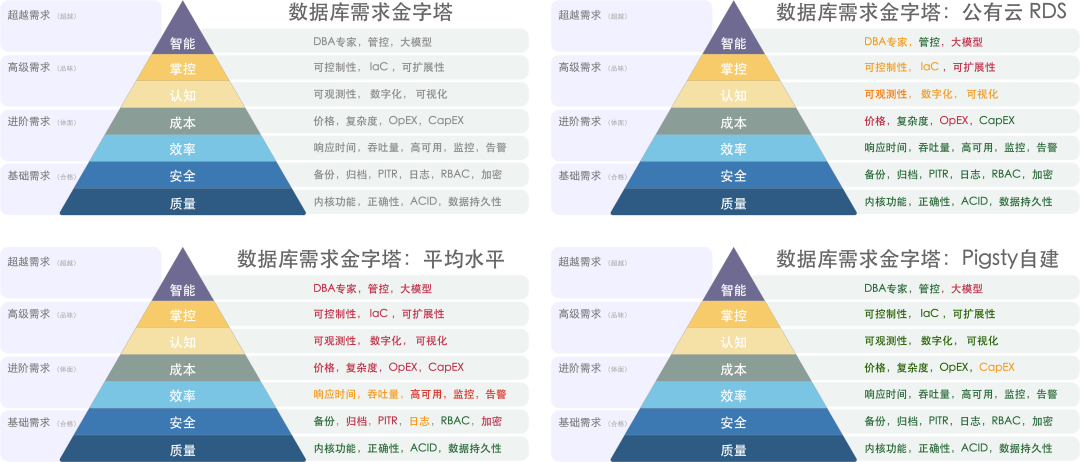

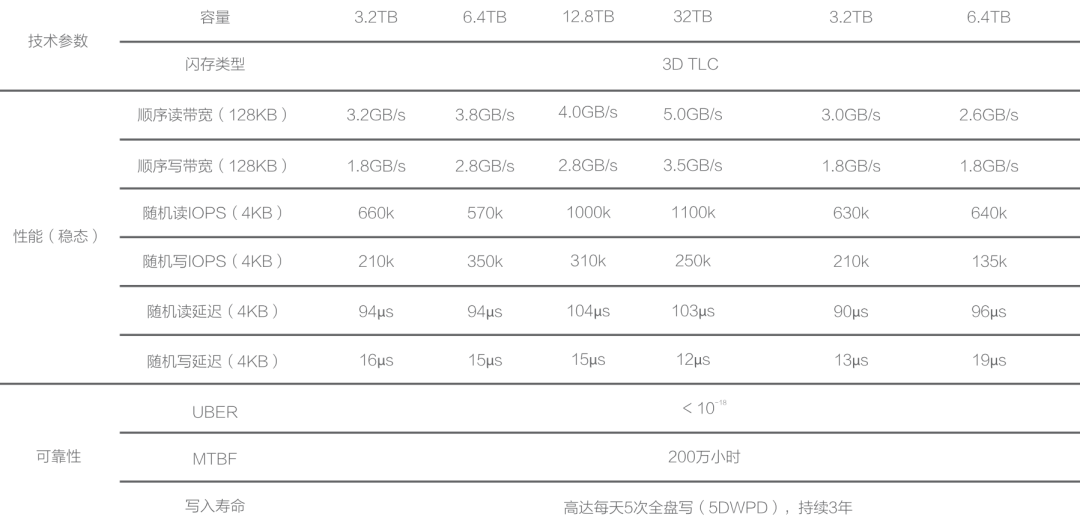

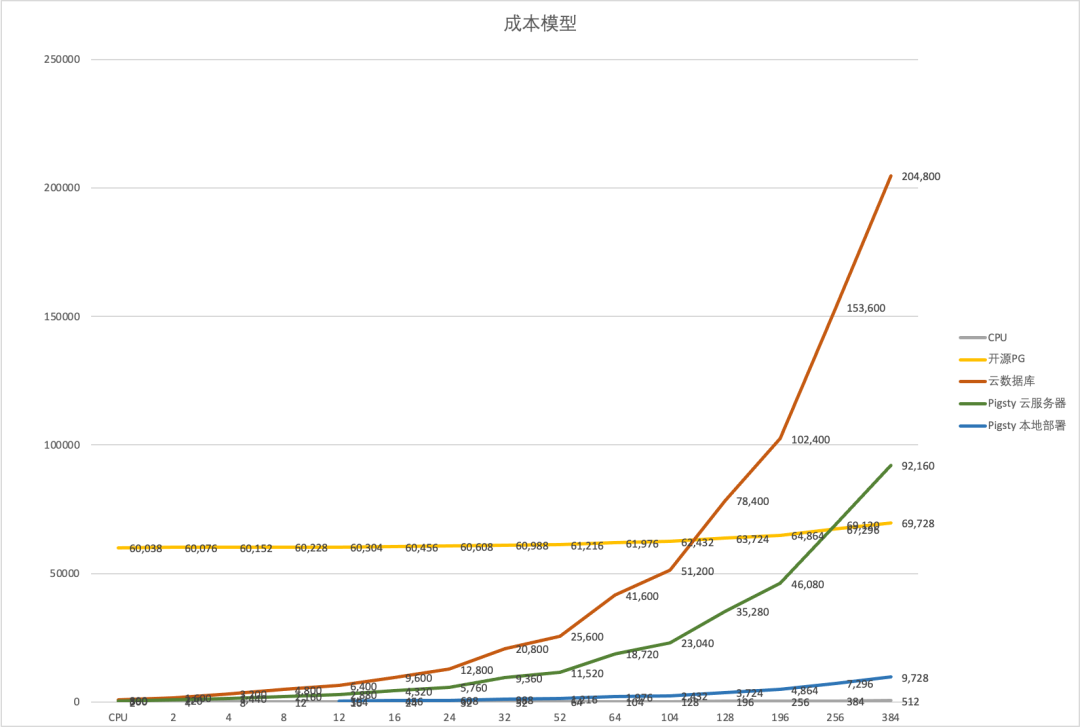

The challenges OpenAI raised are not really from PostgreSQL itself, but from the additional limitations of managed cloud services. One solution is to use the IaaS layer and self-host a PostgreSQL cluster on instances with local NVMe SSD storage to bypass these restrictions.

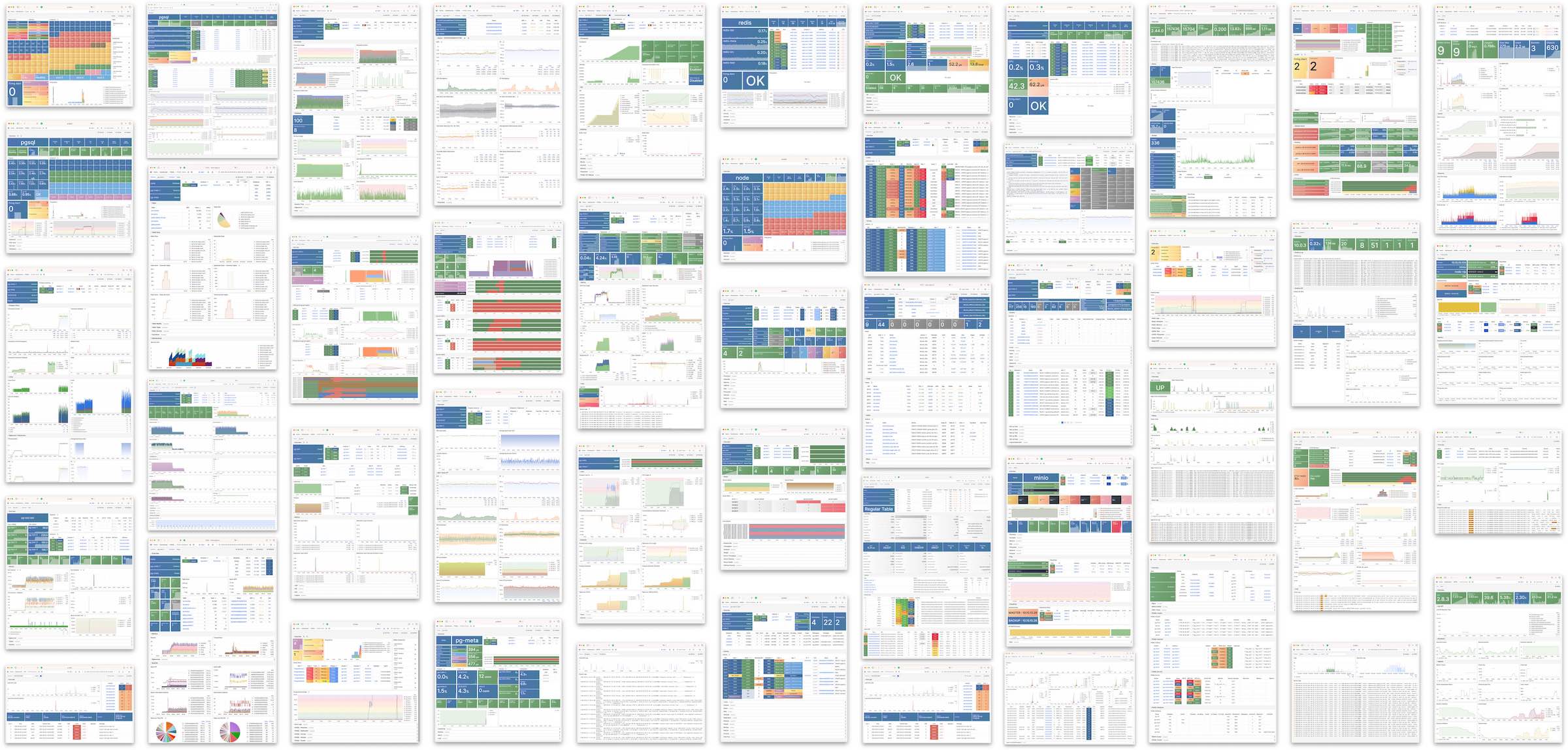

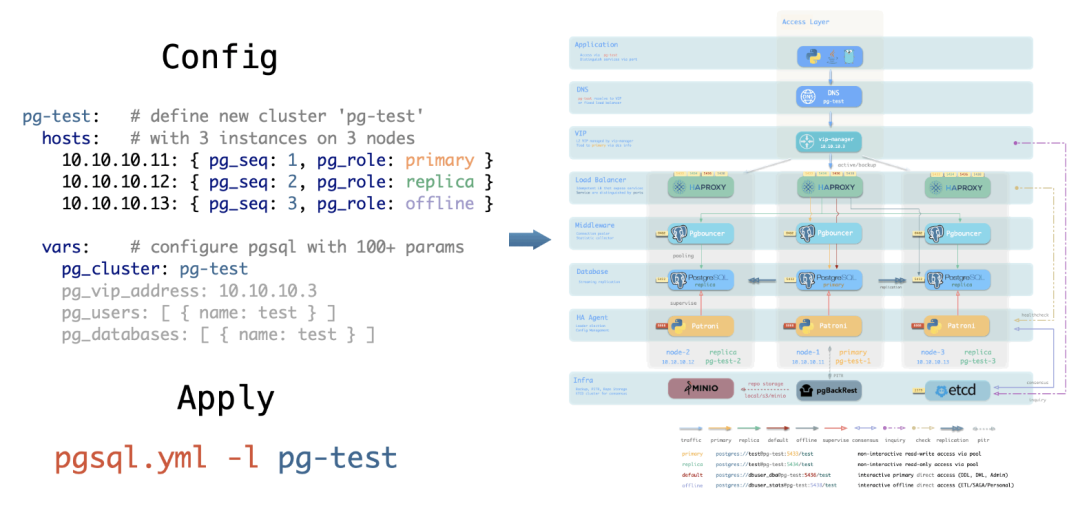

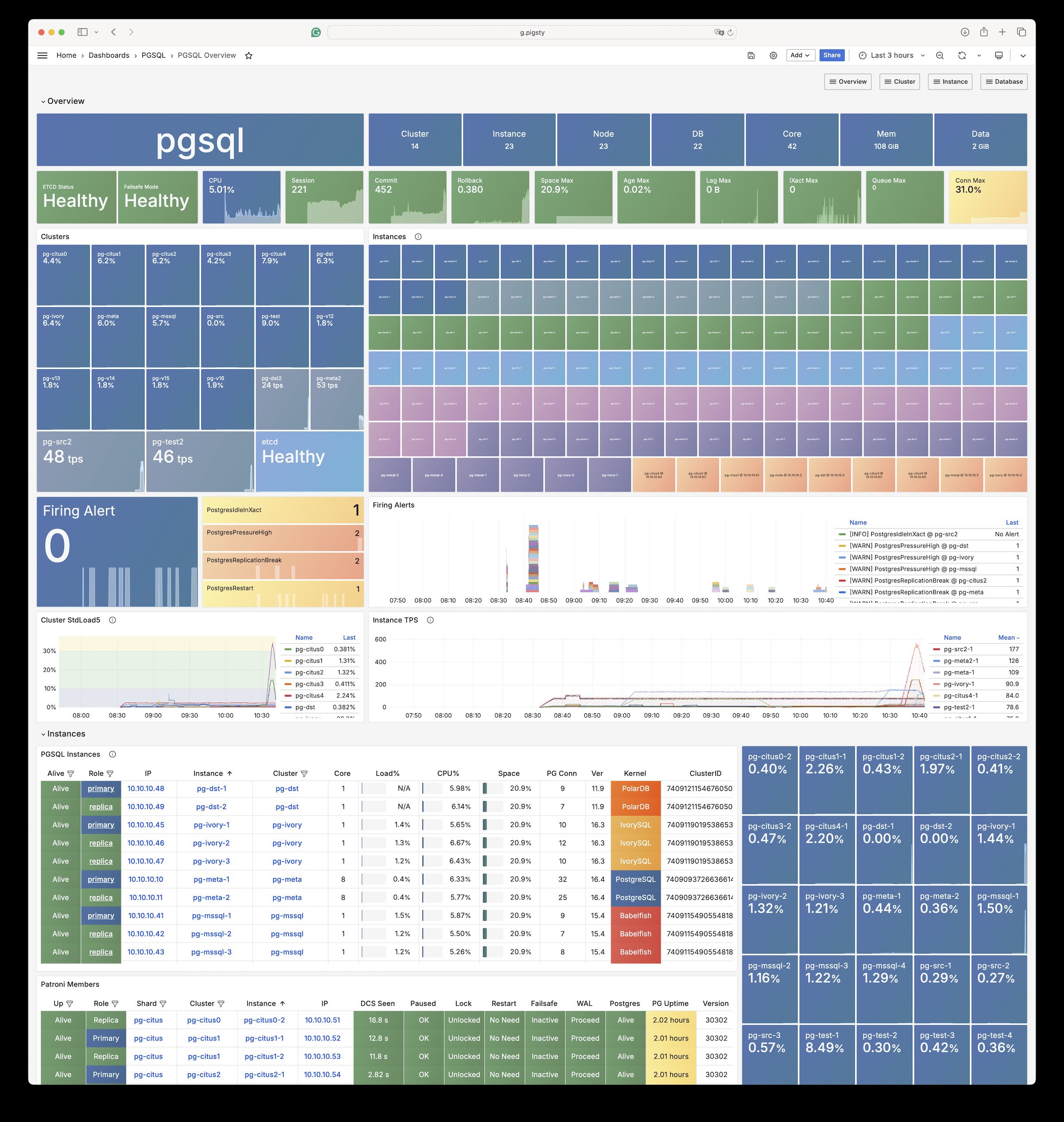

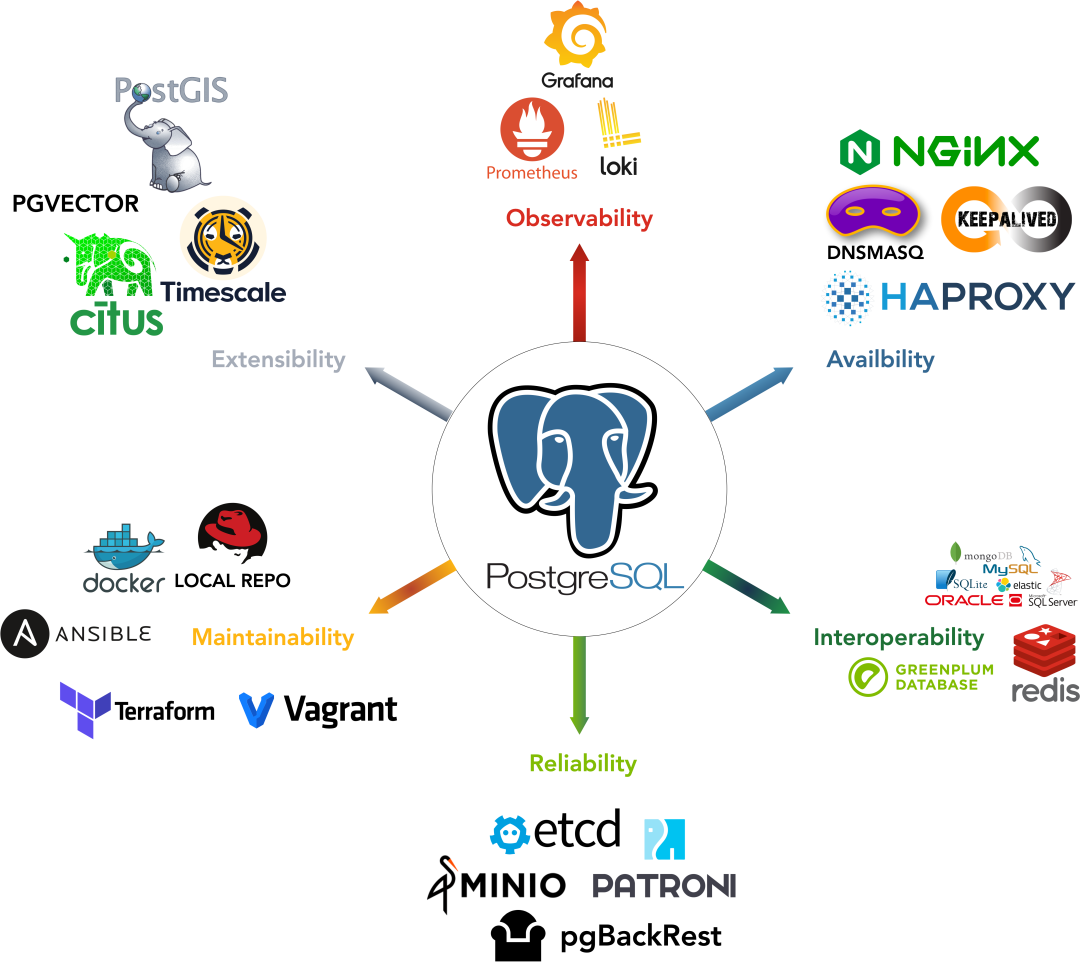

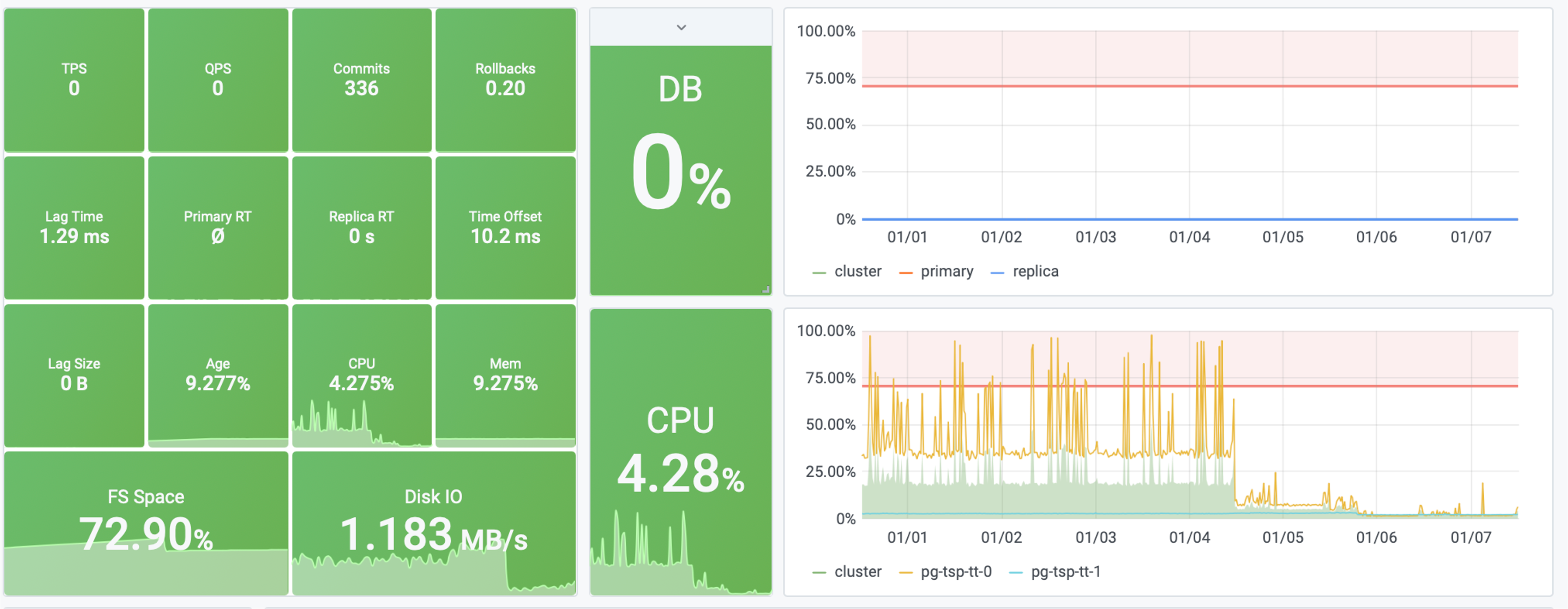

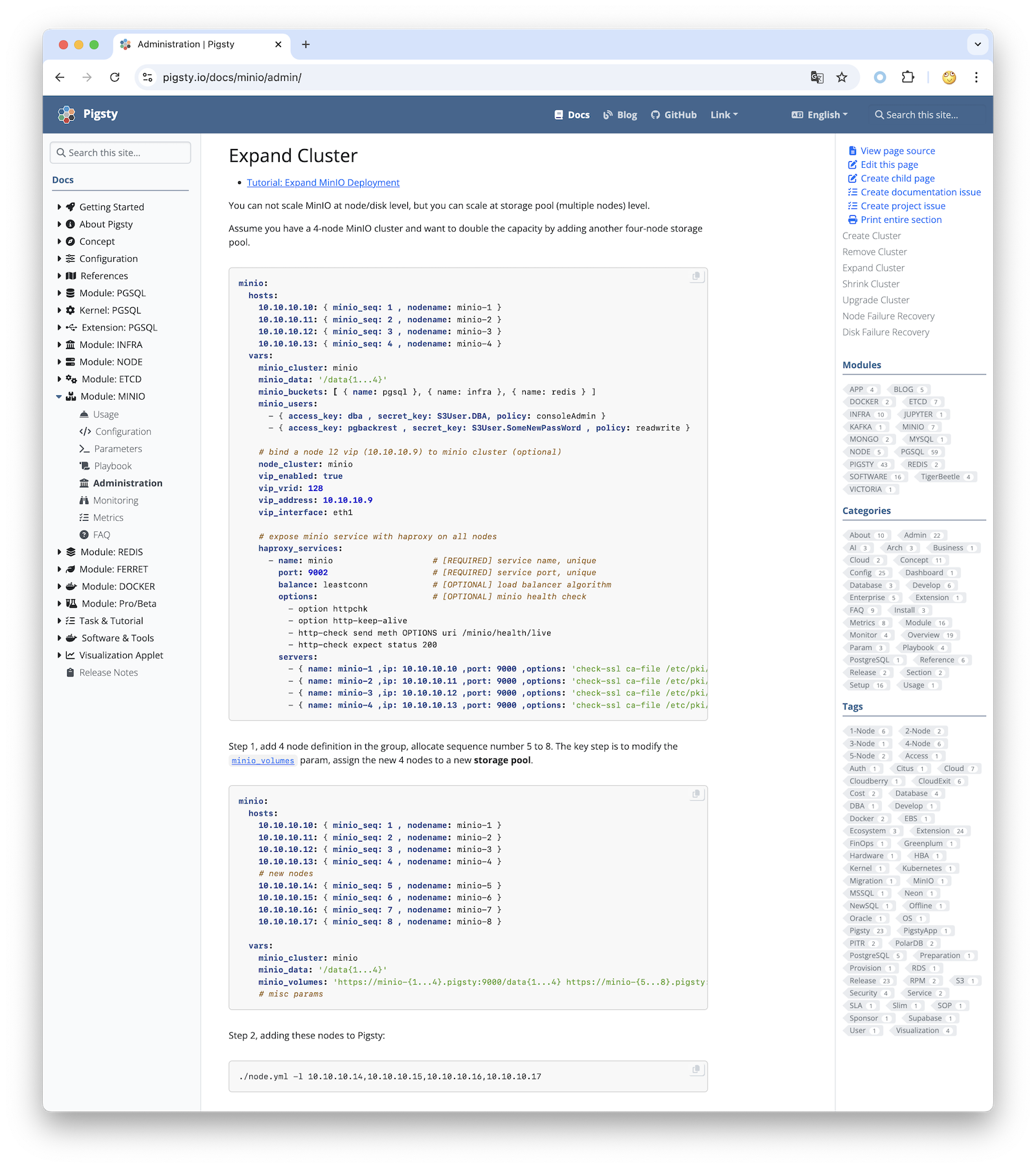

In fact, my project Pigsty built for ourselves to solve PostgreSQL challenges at a similar scale. It scales well, having supported Tantan’s 25K vCPU PostgreSQL cluster and 2.5M QPS. It includes solutions for all the problems mentioned above, and even for many that OpenAI hasn’t encountered yet. And in a self-hosting manner, open-source, free, and ready to use out of the box.

If OpenAI is interested, I’d certainly be happy to provide some help. But I think when you’re in a phase of hyper-growth, fiddling with database infra is probably not a high-priority item. Fortunately, they still have excellent PostgreSQL DBAs who can continue to forge these paths.

References

[1] HackerNews OpenAI: Scaling Postgres to the Next Level: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=44071418#44072781

[2] PostgreSQL is eating the database world: https://pigsty.io/blog/pg/pg-eat-db-world

[3] Chinese: Scaling Postgres to the Next Level at OpenAI https://pigsty.cc/blog/db/openai-pg/

[4] The part of PostgreSQL we hate the most: https://www.cs.cmu.edu/~pavlo/blog/2023/04/the-part-of-postgresql-we-hate-the-most.html

[5] PGConf.Dev 2025: https://2025.pgconf.dev/schedule.html

[6] Schedule: Scaling Postgres to the next level at OpenAI: https://www.pgevents.ca/events/pgconfdev2025/schedule/session/433-scaling-postgres-to-the-next-level-at-openai/

[7] Bohan Zhang: https://www.linkedin.com/in/bohan-zhang-52b17714b

[8] Ruohang Feng / Vonng: https://github.com/Vonng/

[9] Pigsty: https://pigsty.io

[10] Instagram’s Sharding IDs: https://instagram-engineering.com/sharding-ids-at-instagram-1cf5a71e5a5c

[11] Reclaim hardware bouns: https://pigsty.io/blog/cloud/bonus/

[12] Distributed Databases Are a False Need: https://pigsty.io/blog/db/distributive-bullshit/

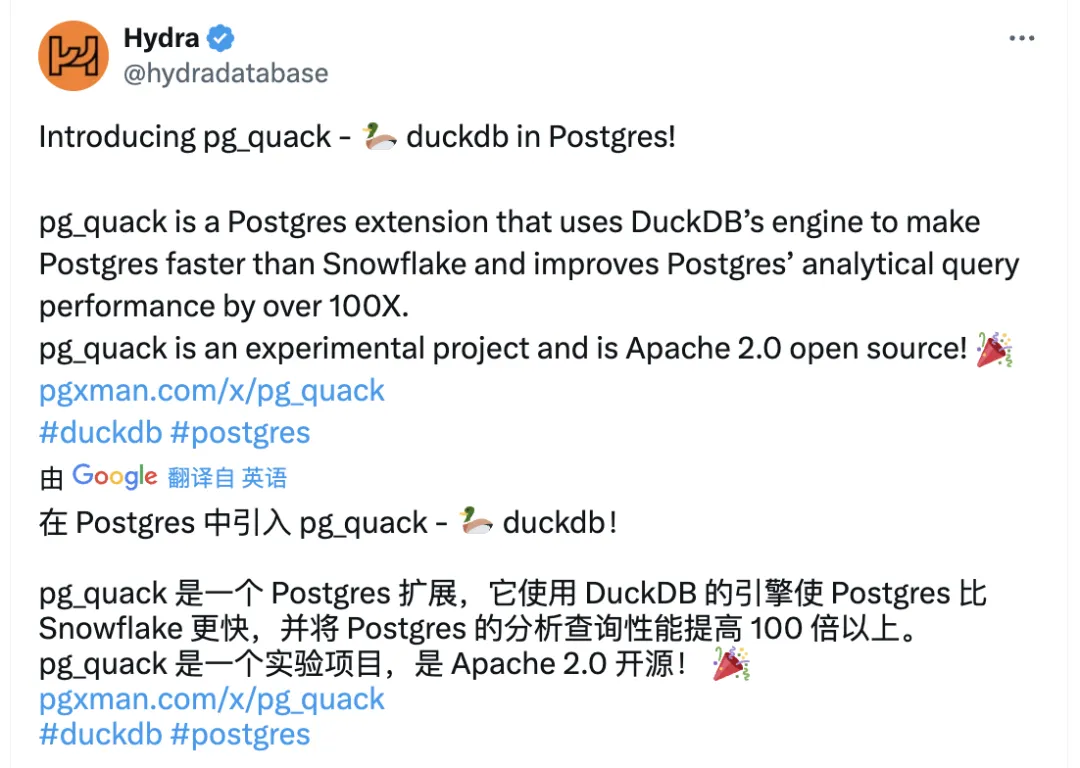

Database Planet Collision: When PG Falls for DuckDB

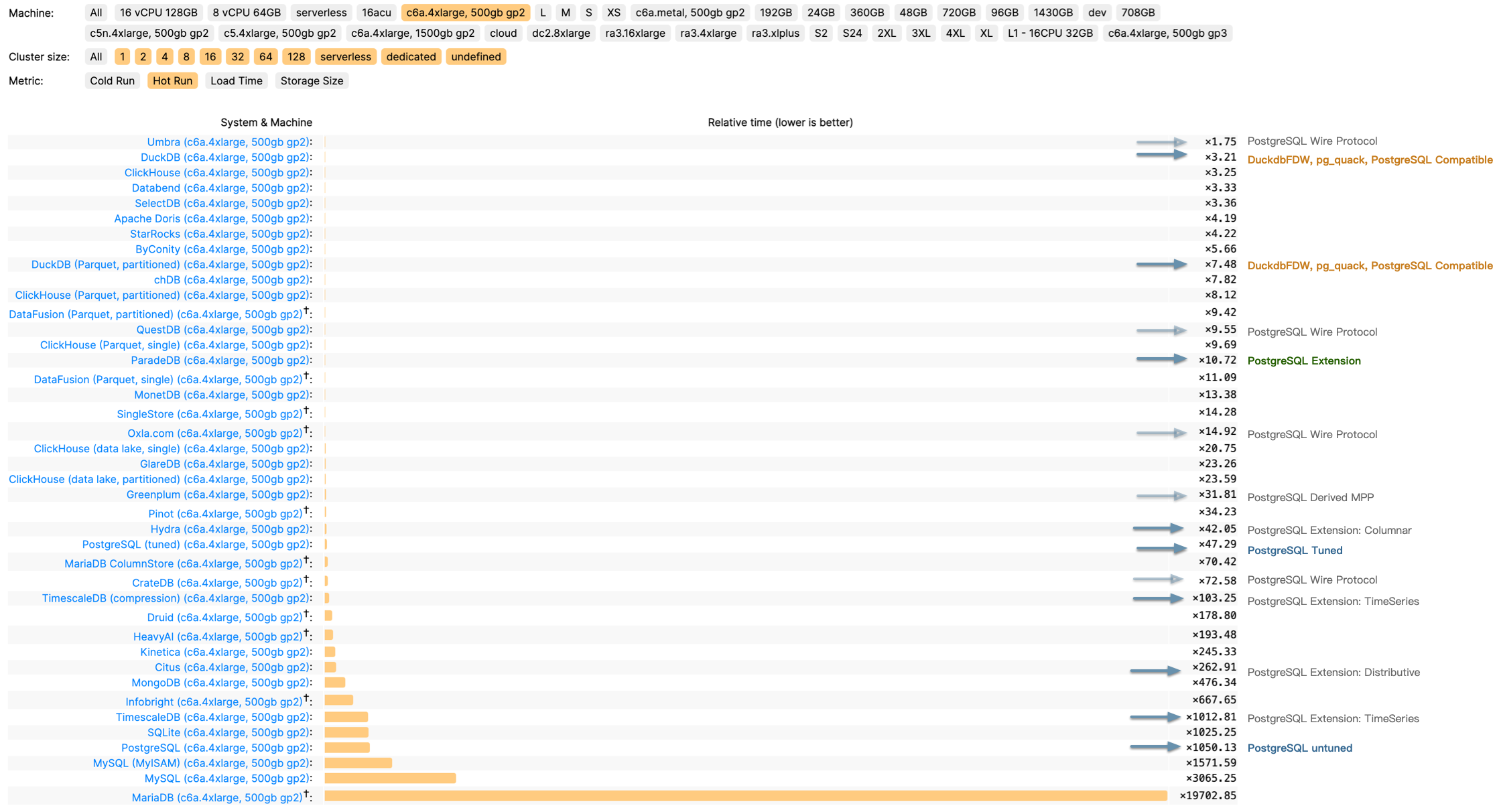

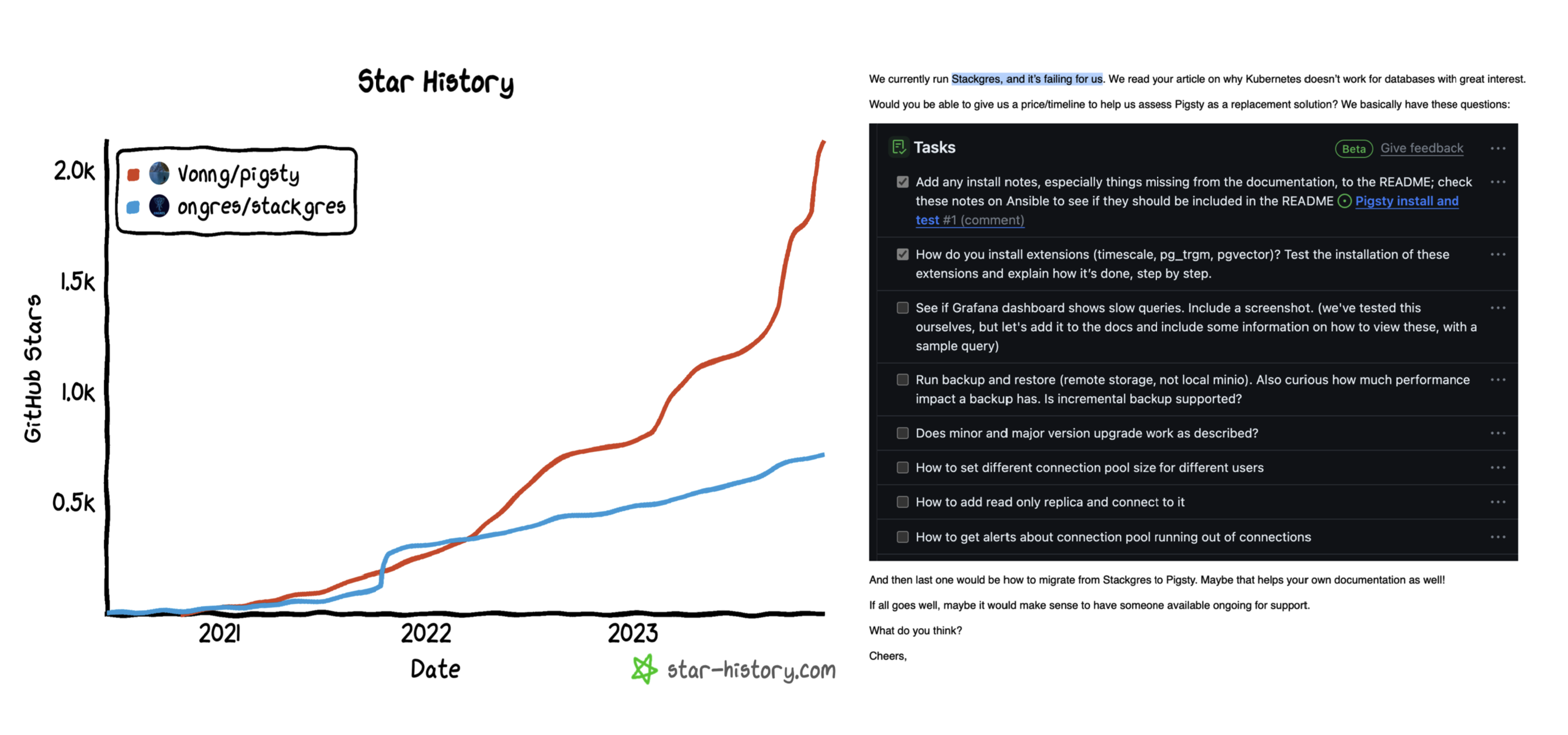

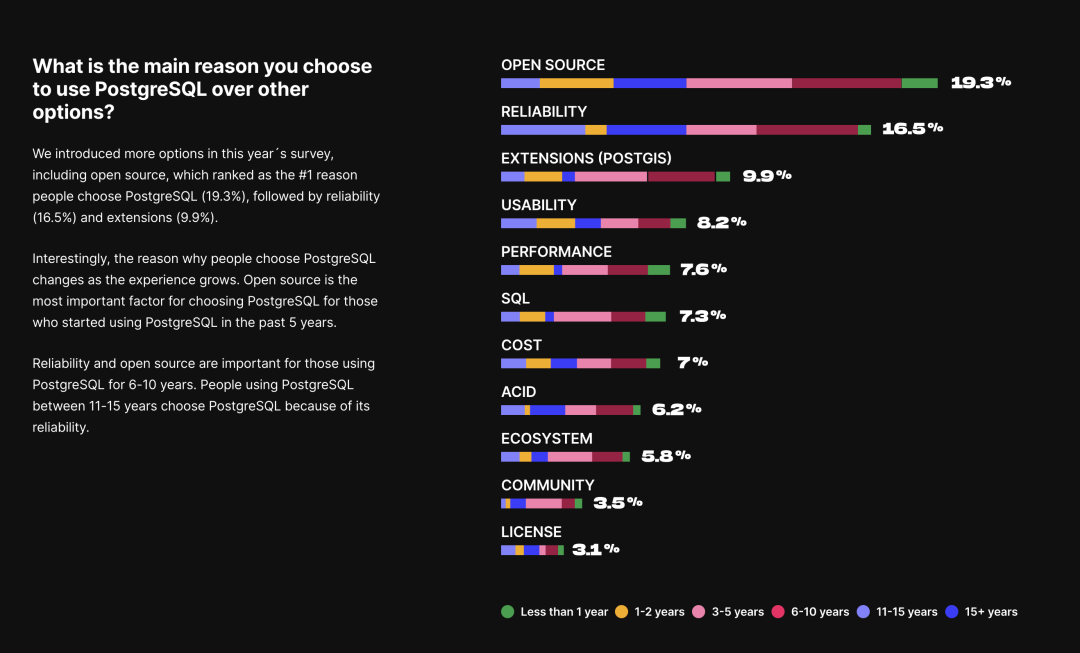

When I published “PostgreSQL Is Eating the Database World” last year, I tossed out this wild idea: Could Postgres really unify OLTP and OLAP? I had no clue we’d see fireworks so quickly.

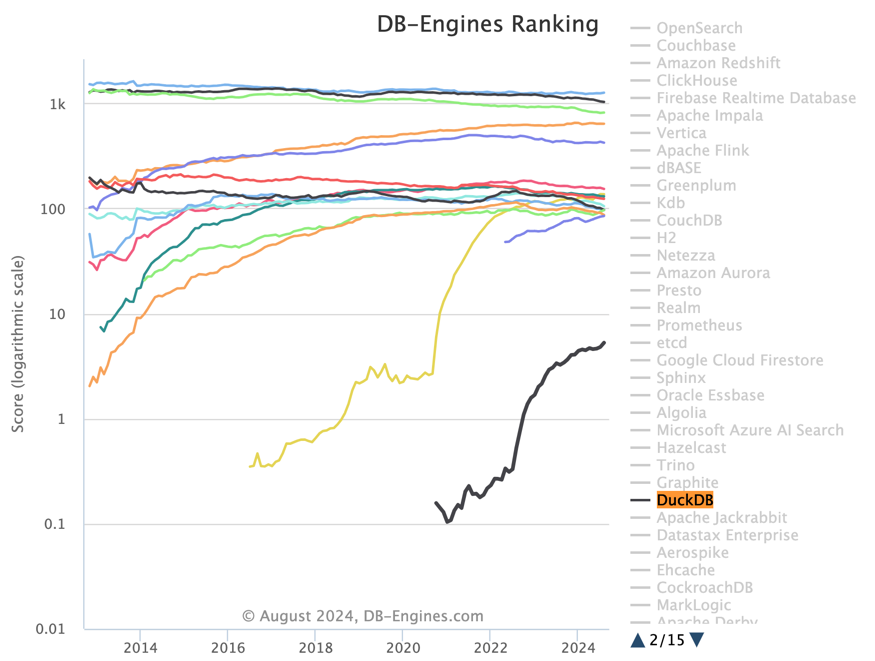

The PG community’s now in an all-out frenzy to stitch DuckDB into the Postgres bloodstream — big enough for Andy Pavlo to give it prime-time coverage in his 2024 database retrospective. If you ask me, we’re on the brink of a cosmic collision in database-land, and Postgres + DuckDB is the meteor we should all be watching.

DuckDB as an OLAP Challenger

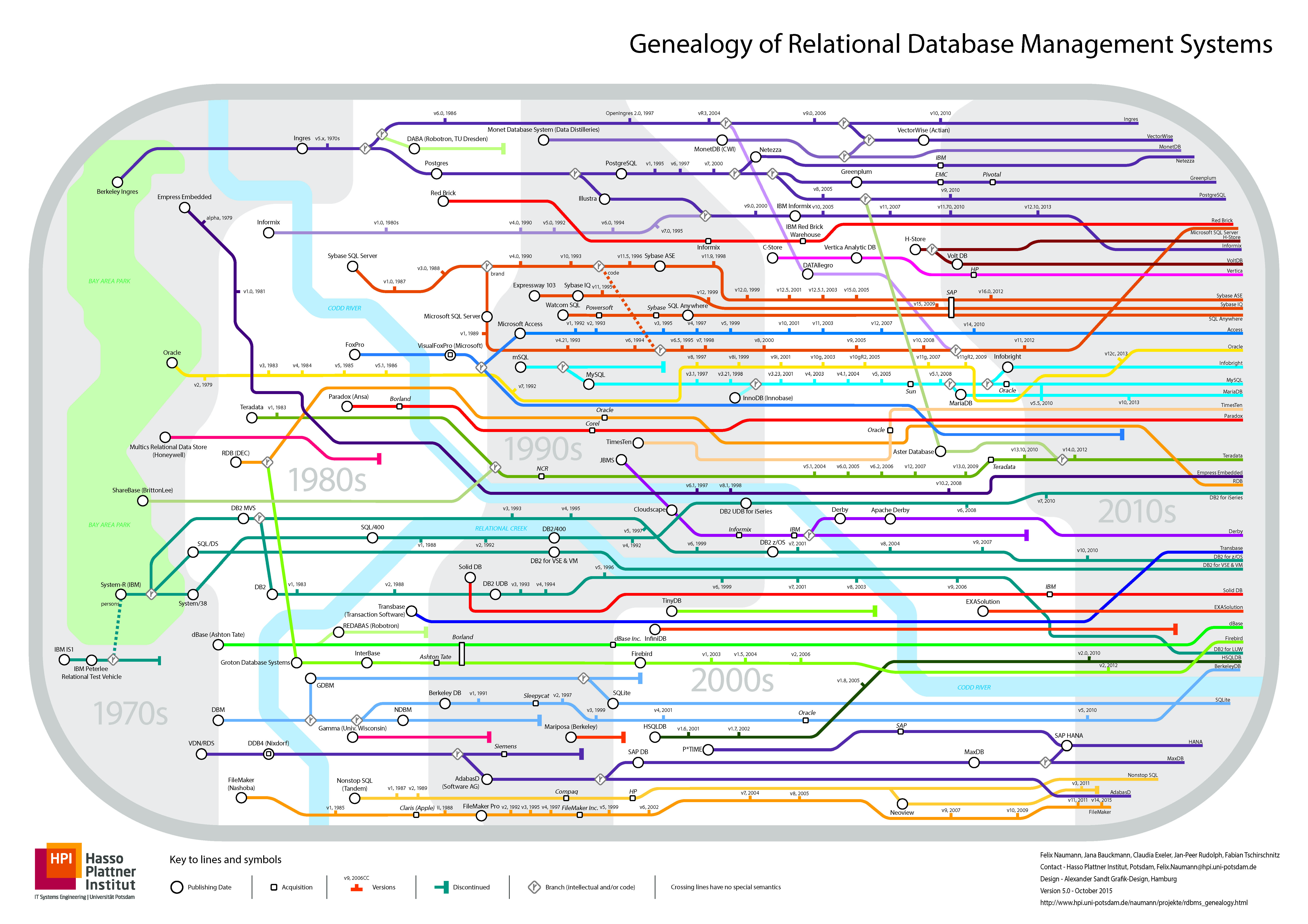

DuckDB came to life at CWI, the Netherlands’ National Research Institute for Mathematics and Computer Science, founded by Mark Raasveldt and Hannes Mühleisen. CWI might look like a quiet research outfit, but it’s actually the secret sauce behind numerous analytic databases—pioneering columnar storage and vectorized queries that power systems like ClickHouse, Snowflake, and Databricks.

After helping guide these heavy hitters, the same minds built DuckDB—an embedded OLAP database for a new generation. Their timing and niche were spot on.

Why DuckDB? The creators noticed data scientists often prefer Python and Pandas, and they’d rather avoid wrestling with heavyweight RDBMS overhead, user authentication, data import/export tangles, etc. DuckDB’s solution? An embedded, SQLite-like analyzer that’s as simple as it gets.

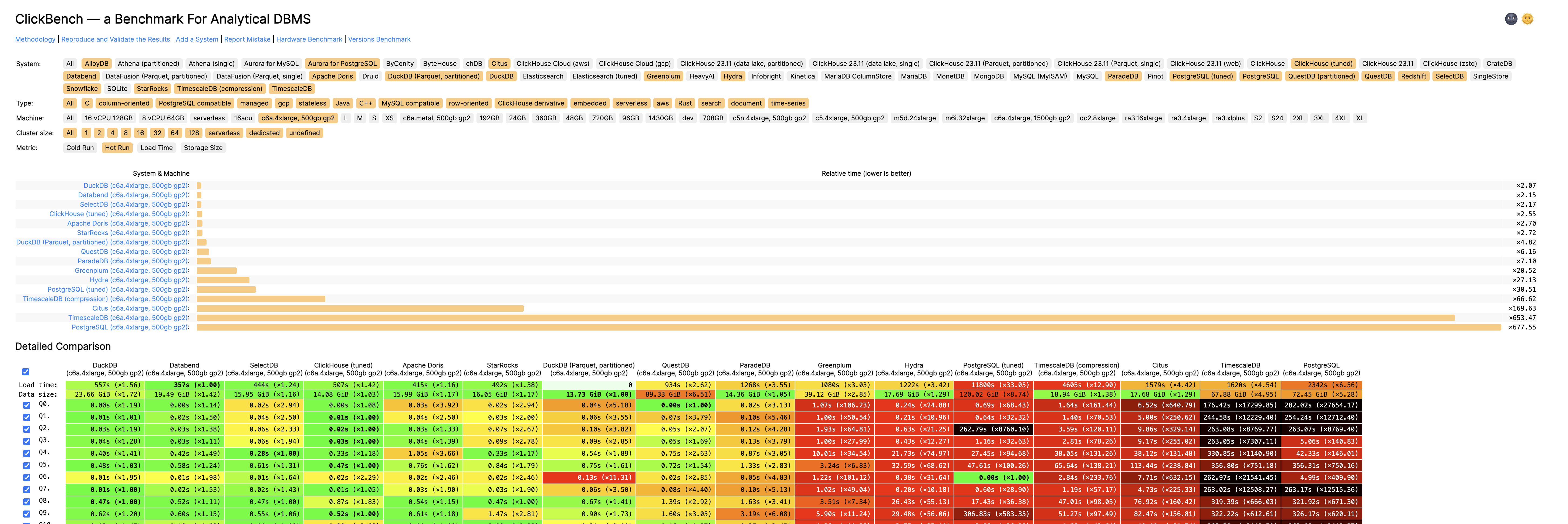

It compiles down to a single binary from just a C++ file and a header. The database itself is just a file on disk. Its SQL syntax and parser come straight from Postgres, creating practically zero friction. Despite its minimalist packaging, DuckDB is a performance beast—besting ClickHouse in some ClickBench tests on ClickHouse’s own turf.

And since DuckDB lands under the MIT license, you get blazing-fast analytics, super-simple onboarding, open source freedom, and any-wrap-you-want packaging. Hard to imagine it not going viral.

The Golden Combo: Strengths and Weaknesses

For all its top-notch OLAP chops, DuckDB’s Achilles’ heel is data management—users, permissions, concurrency, backups, HA…basically all the stuff data scientists love to skip. Ironically, that’s the sweet spot of traditional databases, and it’s also the most painful piece for enterprises.

Hence, DuckDB feels more like an “OLAP operator” or a storage engine, akin to RocksDB, and less like a fully operational “big data platform.”

Meanwhile, PostgreSQL has spent decades polishing data management—rock-solid transactions, access control, backups, HA, a healthy extension ecosystem, and so on. As an OLTP juggernaut, Postgres is a performence beast.. The only lingering complaint is that while Postgres handles standard analytics adequately, it still lags behind specialized OLAP systems when data volumes balloon.

But what if we combine PostgreSQL for data management with DuckDB for high-speed analytics? If these two join forces deeply, we could see a brand-new hybrid in the DB universe.

DuckDB patches Postgres’s bulk-analytics limitations—plus, it can read and write external columnar formats like Parquet in object stores, unleashing a near-infinite data lake. Conversely, DuckDB’s weaker management features get covered by the veteran Postgres ecosystem. Instead of rolling out a brand-new “big data platform” or forging a separate “analytic engine” for Postgres, hooking them together is arguably the simplest and most valuable route.

And guess what—it’s already happening. Multiple teams and vendors are weaving DuckDB into Postgres, racing to open up a massive untapped market.

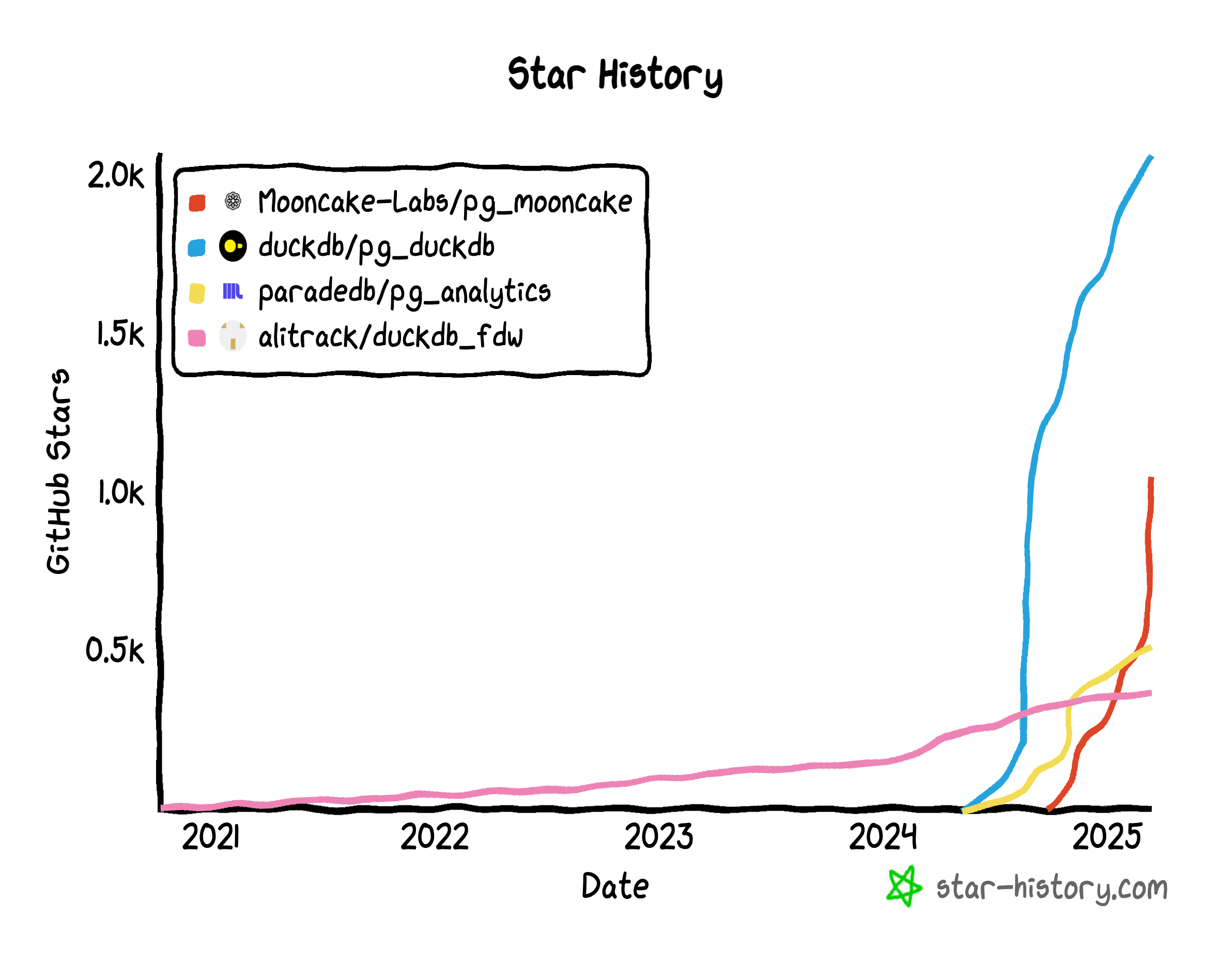

The Race to Stitch Them Together

Take a quick peek and you’ll see competition is fierce

- A lone-wolf developer in China, Steven Lee, kicked things off with

duckdb_fdw. It flew under the radar for a while, but definitely laid groundwork. - After the post “PostgreSQL Is Eating the Database World” used vector databases as a hint toward future OLAP, the PG crowd got charged up about grafting DuckDB onto Postgres.

- By March 2024, ParadeDB retooled

pg_analyticsto stitch in DuckDB. - Hydra, in the PG ecosystem, and DuckDB’s parent MotherDuck launched

pg_duckdb. DuckDB officially jumped into Postgres integration — ironically pausing their own direct approachhydrafor a long time. - Neon, always quick to ride the wave, sponsored

pg_mooncake, built onpg_duckdb. It aims to embed DuckDB’s compute engine in PG while also fusing Parquet-based lakehouse storage. - Even big clouds like Alibaba Cloud RDS are experimenting with DuckDB add-ons (

rds_duckdb). That’s a sure sign the giants have caught on.

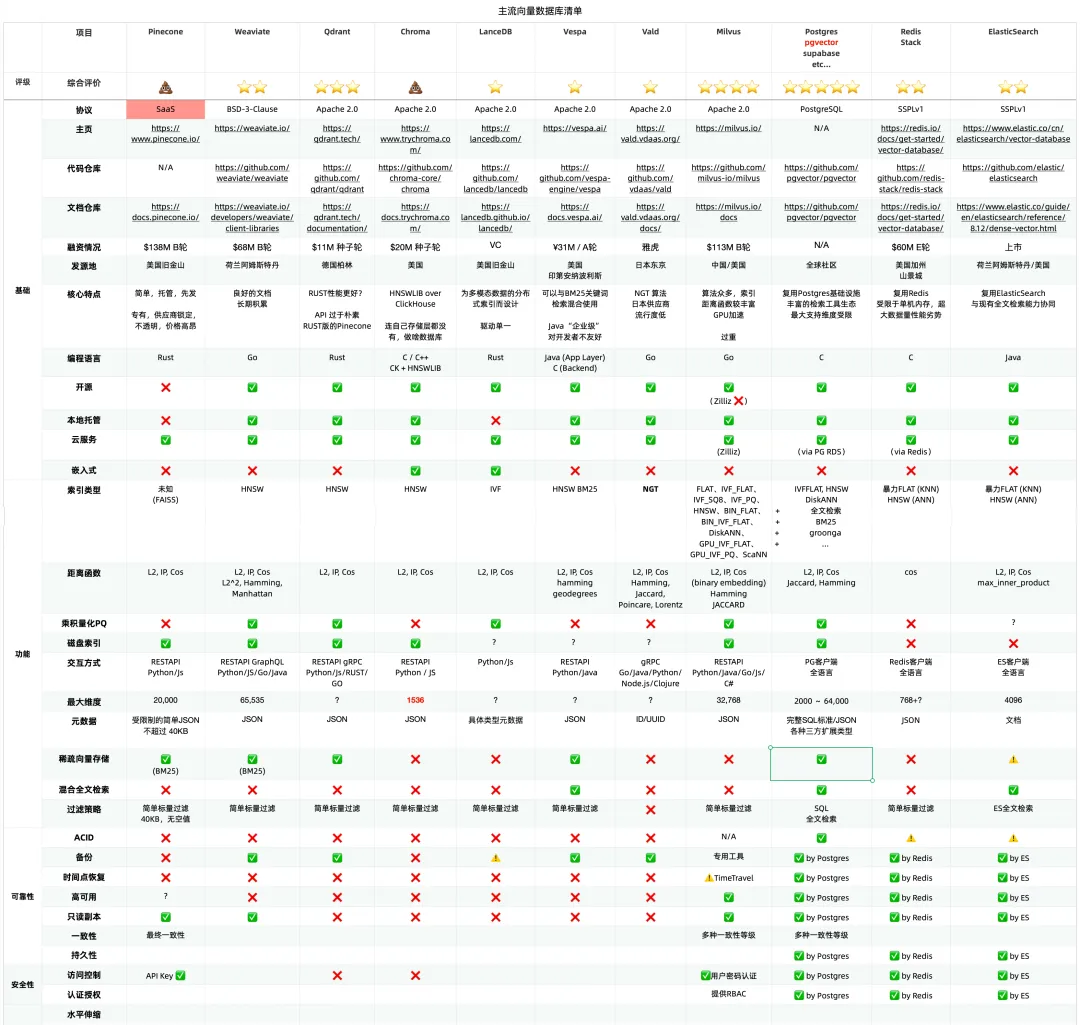

It’s eerily reminiscent of the vector-database frenzy. Once AI and semantic search took off, vendors piled on. In Postgres alone, at least six vector DB extensions sprang up: pgvector, pgvector.rs, pg_embedding, latern, pase, pgvectorscale. It was a good ol’ Wild West. Ultimately, pgvector—fueled by AWS—triumphed, overshadowing latecomers from Oracle/MySQL/MariaDB. Now OLAP might be next in line.

Why DuckDB + Postgres?

Some folks might ask: If we want DuckDB’s power, why not fuse it with MySQL, Oracle, SQL Server, or even MongoDB? Don’t they all crave sharper OLAP?

But Postgres and DuckDB fit like a glove. The synergy boils down to three points:

-

Syntax Compatibility. DuckDB practically clones Postgres syntax and parser, meaning near-zero friction.

-

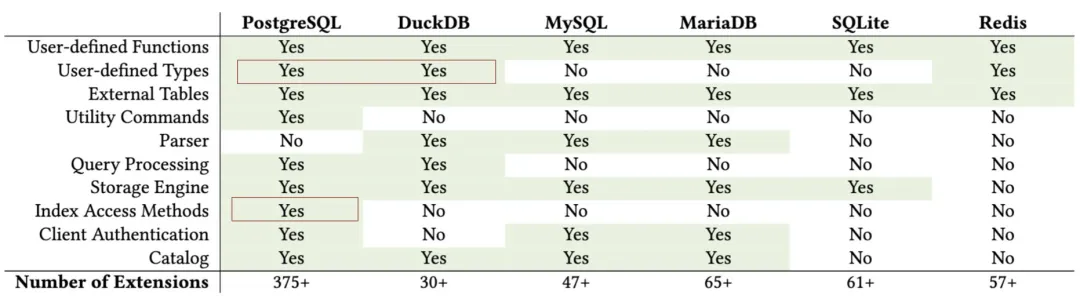

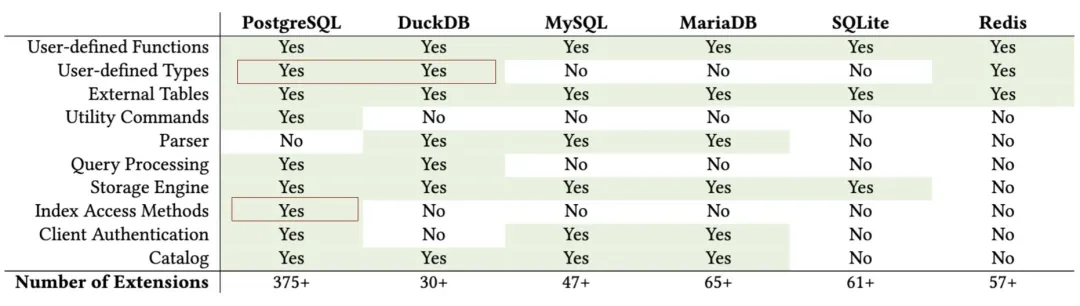

Extensibility. Both Postgres and DuckDB are known for “extensibility mania.” FDWs, storage engines, custom data types—any piece can snap in as an extension. No need to hack deep into either codebase when you can build a bridging extension.

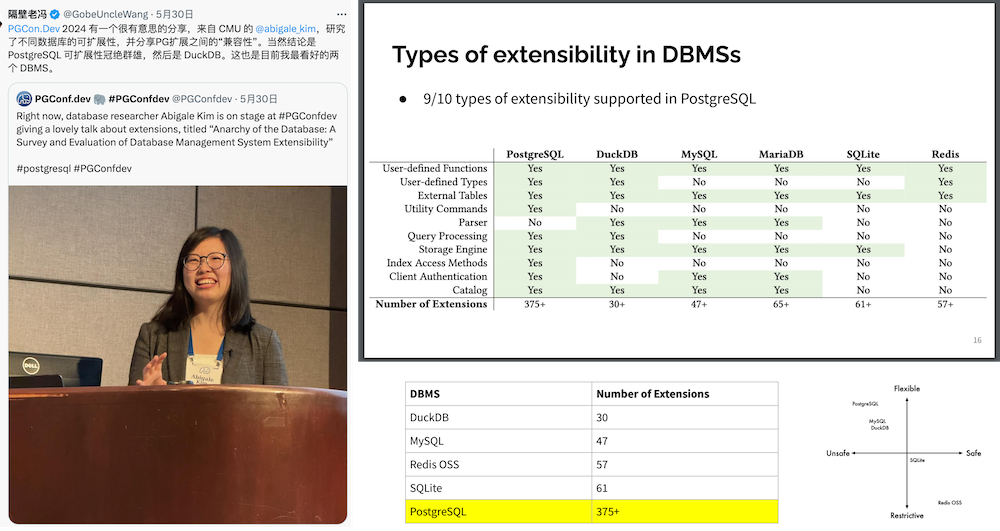

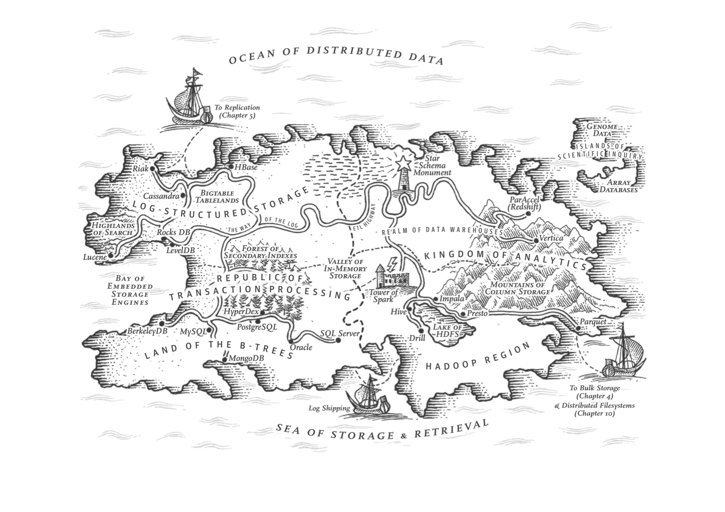

Survey and Evaluation of Database Management System Extensibility

-

Massive Market. Postgres is already the world’s most popular database and the only major RDBMS still growing fast. Integrating with PG brings way more mileage than targeting smaller players.

Hence, hooking Postgres + DuckDB is like a “path of least resistance for maximum impact.” Nature abhors a vacuum, so everyone’s rushing in.

The Dream: One System for OLTP and OLAP

OLTP vs. OLAP has historically been a massive fault line in databases. We’ve spent decades patching it up with data warehouses, separate RDBMS solutions, ETL pipelines, and more. But if Postgres can maintain its OLTP might while leveraging DuckDB for analytics, do we really need an extra analytics DB?

That scenario suggests huge cost savings and simpler engineering. No more data migration migraines or maintaining two different data stacks. Anyone who nails that seamless integration might detonate a deep-sea bomb in the big-data market.

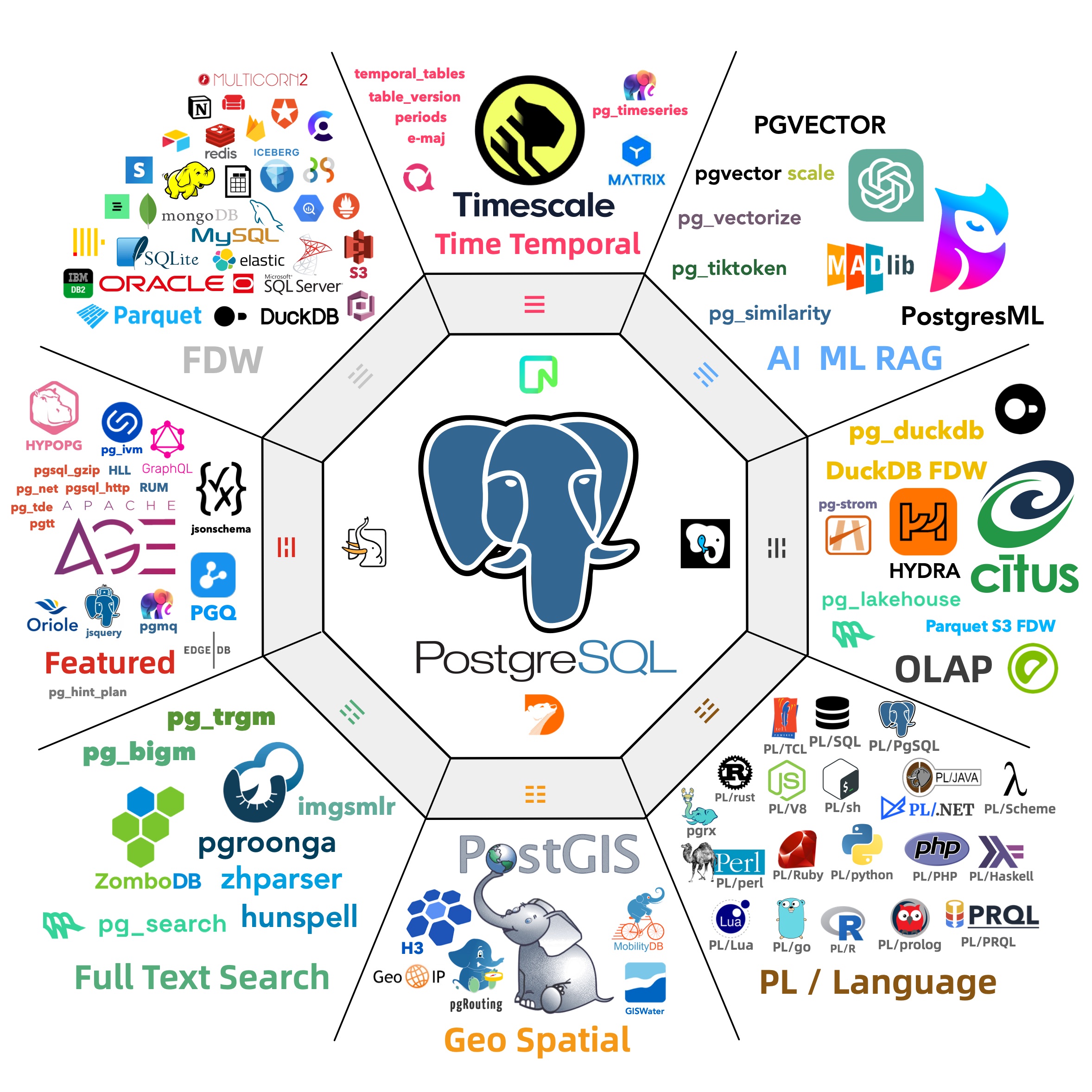

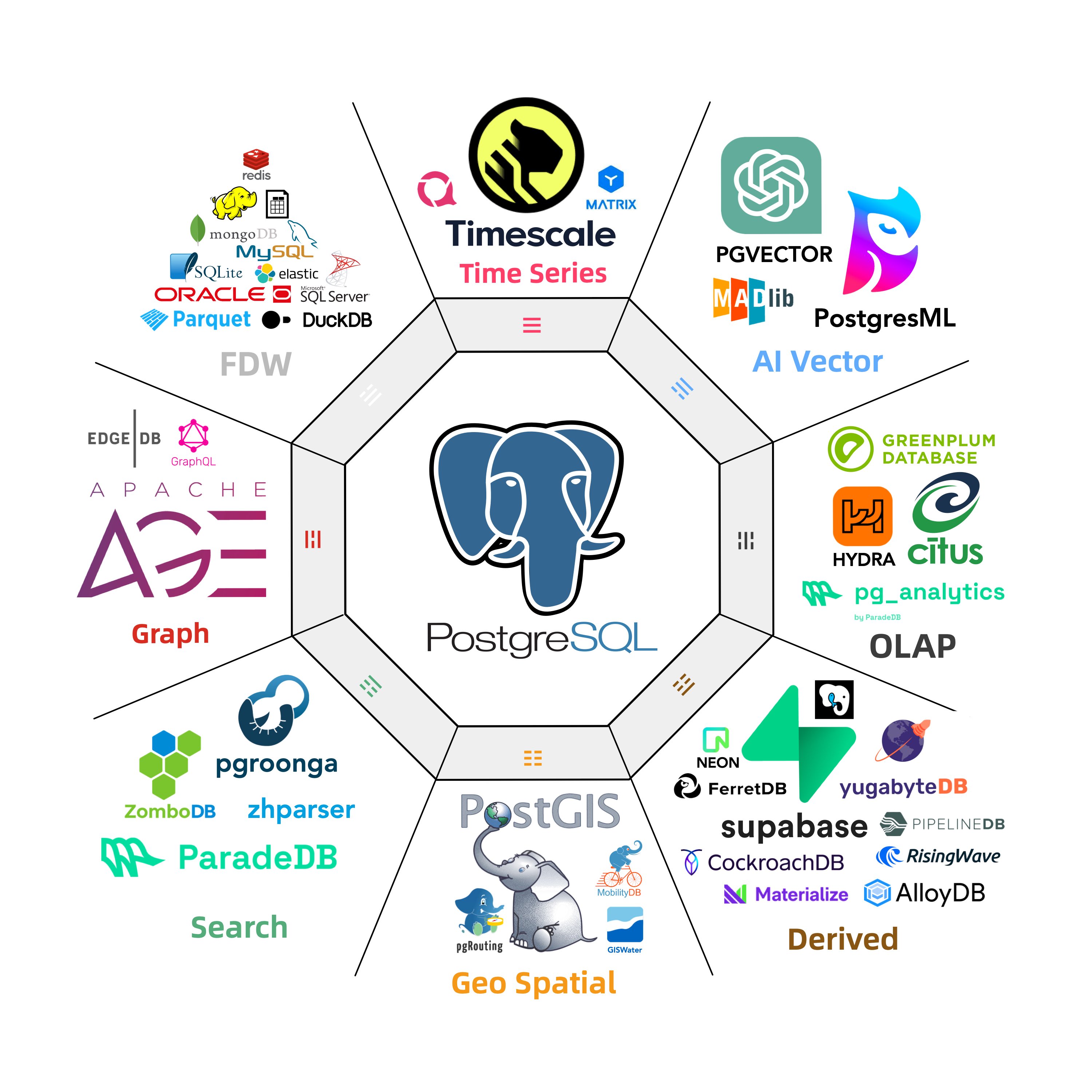

People call Postgres the “Linux kernel of databases” — open source, infinitely extensible, morphable into anything: even mimic MySQL, Oracle, MsSQL and Mongo. We’ve already watched PG conquer geospatial, time series, NoSQL, and vector search through its extension hooks. OLAP might just be its biggest conquest yet.

A polished “plug-and-play” DuckDB integration could flip big data analytics on its head. Will specialized OLAP services withstand a nuclear-level blow? Could they end up like “specialized vector DBs” overshadowed by pgvector? We don’t know, but we’ll definitely have opinions once the dust settles.

Paving the Way for PG + DuckDB

Right now, Postgres OLAP extensions feel like the early vector DB days—small community, big excitement. The beauty of fresh tech is that if you spot the potential, you can jump in early and catch the wave.

When pgvector was just getting started, Pigsty was among the first adopters, right behind Supabase & Neon. I even suggested it be added to PGDG’s yum repos. Now, with the DuckDB stitching craze, you can bet I’ll do better.

As a seasoned data hand, I’m bundling all the PG+DuckDB integration extensions into simple RPMs/DEBs for major Linux distros., fully compatible with official PGDG binaries. Anyone can install them and start playing with “DuckDB+PG” in minutes — call it a battleground where the new contenders can test their mettle on equal footing.

The missing package manager for PostgreSQL:

pig

| Name (Detail) | Repo | Description |

|---|---|---|

| citus | PIGSTY | Distributed PostgreSQL as an extension |

| citus_columnar | PIGSTY | Citus columnar storage engine |

| hydra | PIGSTY | Hydra Columnar extension |

| pg_analytics | PIGSTY | Postgres for analytics, powered by DuckDB |

| pg_duckdb | PIGSTY | DuckDB Embedded in Postgres |

| pg_mooncake | PIGSTY | Columnstore Table in Postgres |

| duckdb_fdw | PIGSTY | DuckDB Foreign Data Wrapper |

| pg_parquet | PIGSTY | copy data between Postgres and Parquet |

| pg_fkpart | MIXED | Table partitioning by foreign key utility |

| pg_partman | PGDG | Extension to manage partitioned tables by time or ID |

| plproxy | PGDG | Database partitioning implemented as procedural language |

| pg_strom | PGDG | PG-Strom - big-data processing acceleration using GPU and NVME |

| tablefunc | CONTRIB | functions that manipulate whole tables, including crosstab |

Sure, a lot of these plugins are alpha/beta: concurrency quirks, partial feature sets, performance oddities. But fortune favors the bold. I’m convinced this “PG + DuckDB” show is about to take center stage.

The Real Explosion Is Coming

In enterprise circles, OLAP dwarfs most hype markets by sheer scale and practicality. Meanwhile, Postgres + DuckDB looks set to disrupt this space further, possibly demolishing the old “RDBMS + big data” two-stack architecture.

In months—or a year or two—we might see a new wave of “chimera” systems spring from these extension projects and claim the database spotlight. Whichever team nails usability, integration, and performance first will seize a formidable edge.

For database vendors, this is an epic collision; for businesses, it’s a chance to do more with less. Let’s see how the dust settles—and how it reshapes the future of data analytics and management.

Further Reading

- PostgreSQL Is Eating the Database World

- Whoever Masters DuckDB Integration Wins the OLAP Database World

- Alibaba Cloud rds_duckdb: Homage or Ripoff?

- Is Distributed Databases a Mythical Need?

- Andy Pavlo’s 2024 Database Recap

Self-Hosting Supabase on PostgreSQL

Supabase is great, own your own Supabase is even better. Here’s a comprehensive tutorial for self-hosting production-grade supabase on local/cloud VM/BMs.

This tutorial is obsolete for the latest pigsty version, Check the latest tutorial here: Self-Hosting Supabase

What is Supabase?

Supabase is an open-source Firebase alternative, a Backend as a Service (BaaS).

Supabase wraps PostgreSQL kernel and vector extensions, alone with authentication, realtime subscriptions, edge functions, object storage, and instant REST and GraphQL APIs from your postgres schema. It let you skip most backend work, requiring only database design and frontend skills to ship quickly.

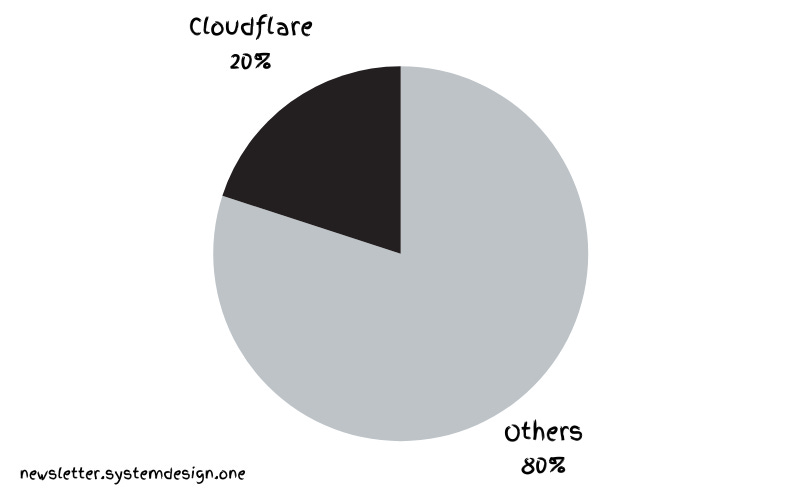

Currently, Supabase may be the most popular open-source project in the PostgreSQL ecosystem, boasting over 74,000 stars on GitHub. And become quite popular among developers, and startups, since they have a generous free plan, just like cloudflare & neon.

Why Self-Hosting?

Supabase’s slogan is: “Build in a weekend, Scale to millions”. It has great cost-effectiveness in small scales (4c8g) indeed. But there is no doubt that when you really grow to millions of users, some may choose to self-hosting their own Supabase —— for functionality, performance, cost, and other reasons.

That’s where Pigsty comes in. Pigsty provides a complete one-click self-hosting solution for Supabase. Self-hosted Supabase can enjoy full PostgreSQL monitoring, IaC, PITR, and high availability capability,

You can run the latest PostgreSQL 17(,16,15,14) kernels, (supabase is using the 15 currently), alone with 421 PostgreSQL extensions out-of-the-box. Run on mainstream Linus OS distros with production grade HA PostgreSQL, MinIO, Prometheus & Grafana Stack for observability, and Nginx for reverse proxy.

Since most of the supabase maintained extensions are not available in the official PGDG repo, we have compiled all the RPM/DEBs for these extensions and put them in the Pigsty repo: pg_graphql, pg_jsonschema, wrappers, index_advisor, pg_net, vault, pgjwt, supautils, pg_plan_filter,…

Everything is under your control, you have the ability and freedom to scale PGSQL, MinIO, and Supabase itself. And take full advantage of the performance and cost advantages of modern hardware like Gen5 NVMe SSD.

All you need is prepare a VM with several commands and wait for 10 minutes….

Get Started

First, download & install pigsty as usual, with the supa config template:

curl -fsSL https://repo.pigsty.io/get | bash; cd ~/pigsty

./bootstrap # install ansible

./configure -c app/supa # use supabase config (please CHANGE CREDENTIALS in pigsty.yml)

vi pigsty.yml # edit domain name, password, keys,...

./install.yml # install pigsty

Please change the

pigsty.ymlconfig file according to your need before deploying Supabase. (Credentials) For dev/test/demo purposes, we will just skip that, and comes back later.

Then, run the docker.yml to install docker, and app.yml to launch stateless part of supabase.

./docker.yml # install docker compose

./app.yml # launch supabase stateless part with docker

You can access the supabase API / Web UI through the 8000/8443 directly.

with configured DNS, or a local /etc/hosts entry, you can also use the default supa.pigsty domain name via the 80/443 infra portal.

Credentials for Supabase Studio:

supabase:pigsty

Architecture

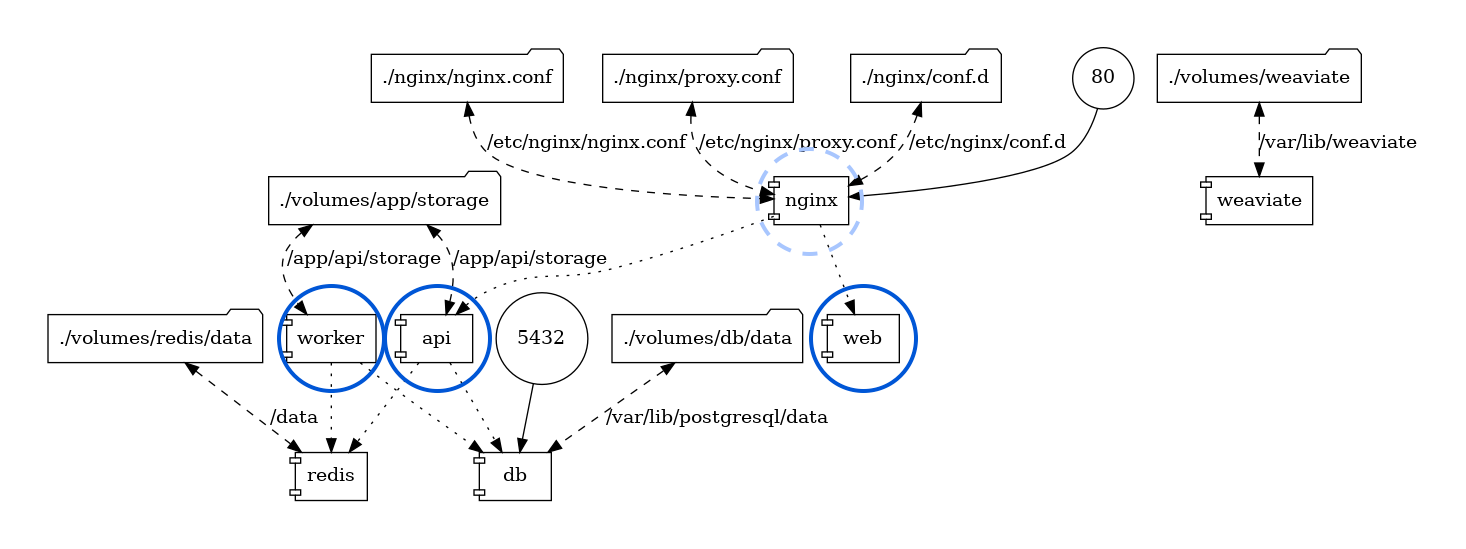

Pigsty’s supabase is based on the Supabase Docker Compose Template, with some slight modifications to fit-in Pigsty’s default ACL model.

The stateful part of this template is replaced by Pigsty’s managed PostgreSQL cluster and MinIO cluster. The container part are stateless, so you can launch / destroy / run multiple supabase containers on the same stateful PGSQL / MINIO cluster simultaneously to scale out.

The built-in supa.yml config template will create a single-node supabase, with a singleton PostgreSQL and SNSD MinIO server.

You can use Multinode PostgreSQL Clusters and MNMD MinIO Clusters / external S3 service instead in production, we will cover that later.

Config Detail

Here are checklists for self-hosting

- Hardware: necessary VM/BM resources, one node at least, 3-4 are recommended for HA.

- Linux OS: Linux x86_64 server with fresh installed Linux, check compatible distro

- Network: Static IPv4 address which can be used as node identity

- Admin User: nopass ssh & sudo are recommended for admin user

- Conf Template: Use the

supaconfig template, if you don’t know how to manually configure pigsty

The built-in supa.yml config template is shown below.

The supa Config Template

all:

children:

# the supabase stateless (default username & password: supabase/pigsty)

supa:

hosts:

10.10.10.10: {}

vars:

app: supabase # specify app name (supa) to be installed (in the apps)

apps: # define all applications

supabase: # the definition of supabase app

conf: # override /opt/supabase/.env

# IMPORTANT: CHANGE JWT_SECRET AND REGENERATE CREDENTIAL ACCORDING!!!!!!!!!!!

# https://supabase.com/docs/guides/self-hosting/docker#securing-your-services

JWT_SECRET: your-super-secret-jwt-token-with-at-least-32-characters-long

ANON_KEY: eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyAgCiAgICAicm9sZSI6ICJhbm9uIiwKICAgICJpc3MiOiAic3VwYWJhc2UtZGVtbyIsCiAgICAiaWF0IjogMTY0MTc2OTIwMCwKICAgICJleHAiOiAxNzk5NTM1NjAwCn0.dc_X5iR_VP_qT0zsiyj_I_OZ2T9FtRU2BBNWN8Bu4GE

SERVICE_ROLE_KEY: eyJhbGciOiJIUzI1NiIsInR5cCI6IkpXVCJ9.eyAgCiAgICAicm9sZSI6ICJzZXJ2aWNlX3JvbGUiLAogICAgImlzcyI6ICJzdXBhYmFzZS1kZW1vIiwKICAgICJpYXQiOiAxNjQxNzY5MjAwLAogICAgImV4cCI6IDE3OTk1MzU2MDAKfQ.DaYlNEoUrrEn2Ig7tqibS-PHK5vgusbcbo7X36XVt4Q

DASHBOARD_USERNAME: supabase

DASHBOARD_PASSWORD: pigsty

# postgres connection string (use the correct ip and port)

POSTGRES_HOST: 10.10.10.10 # point to the local postgres node

POSTGRES_PORT: 5436 # access via the 'default' service, which always route to the primary postgres

POSTGRES_DB: postgres # the supabase underlying database

POSTGRES_PASSWORD: DBUser.Supa # password for supabase_admin and multiple supabase users

# expose supabase via domain name

SITE_URL: https://supa.pigsty # <------- Change This to your external domain name

API_EXTERNAL_URL: https://supa.pigsty # <------- Otherwise the storage api may not work!

SUPABASE_PUBLIC_URL: https://supa.pigsty # <------- DO NOT FORGET TO PUT IT IN infra_portal!

# if using s3/minio as file storage

S3_BUCKET: supa

S3_ENDPOINT: https://sss.pigsty:9000

S3_ACCESS_KEY: supabase

S3_SECRET_KEY: S3User.Supabase

S3_FORCE_PATH_STYLE: true

S3_PROTOCOL: https

S3_REGION: stub

MINIO_DOMAIN_IP: 10.10.10.10 # sss.pigsty domain name will resolve to this ip statically

# if using SMTP (optional)

#SMTP_ADMIN_EMAIL: [email protected]

#SMTP_HOST: supabase-mail

#SMTP_PORT: 2500

#SMTP_USER: fake_mail_user

#SMTP_PASS: fake_mail_password

#SMTP_SENDER_NAME: fake_sender

#ENABLE_ANONYMOUS_USERS: false

# infra cluster for proxy, monitor, alert, etc..

infra: { hosts: { 10.10.10.10: { infra_seq: 1 } } }

# etcd cluster for ha postgres

etcd: { hosts: { 10.10.10.10: { etcd_seq: 1 } }, vars: { etcd_cluster: etcd } }

# minio cluster, s3 compatible object storage

minio: { hosts: { 10.10.10.10: { minio_seq: 1 } }, vars: { minio_cluster: minio } }

# pg-meta, the underlying postgres database for supabase

pg-meta:

hosts: { 10.10.10.10: { pg_seq: 1, pg_role: primary } }

vars:

pg_cluster: pg-meta

pg_users:

# supabase roles: anon, authenticated, dashboard_user

- { name: anon ,login: false }

- { name: authenticated ,login: false }

- { name: dashboard_user ,login: false ,replication: true ,createdb: true ,createrole: true }

- { name: service_role ,login: false ,bypassrls: true }

# supabase users: please use the same password

- { name: supabase_admin ,password: 'DBUser.Supa' ,pgbouncer: true ,inherit: true ,roles: [ dbrole_admin ] ,superuser: true ,replication: true ,createdb: true ,createrole: true ,bypassrls: true }

- { name: authenticator ,password: 'DBUser.Supa' ,pgbouncer: true ,inherit: false ,roles: [ dbrole_admin, authenticated ,anon ,service_role ] }

- { name: supabase_auth_admin ,password: 'DBUser.Supa' ,pgbouncer: true ,inherit: false ,roles: [ dbrole_admin ] ,createrole: true }

- { name: supabase_storage_admin ,password: 'DBUser.Supa' ,pgbouncer: true ,inherit: false ,roles: [ dbrole_admin, authenticated ,anon ,service_role ] ,createrole: true }

- { name: supabase_functions_admin ,password: 'DBUser.Supa' ,pgbouncer: true ,inherit: false ,roles: [ dbrole_admin ] ,createrole: true }

- { name: supabase_replication_admin ,password: 'DBUser.Supa' ,replication: true ,roles: [ dbrole_admin ]}

- { name: supabase_read_only_user ,password: 'DBUser.Supa' ,bypassrls: true ,roles: [ dbrole_readonly, pg_read_all_data ] }

pg_databases:

- name: postgres

baseline: supabase.sql

owner: supabase_admin

comment: supabase postgres database

schemas: [ extensions ,auth ,realtime ,storage ,graphql_public ,supabase_functions ,_analytics ,_realtime ]

extensions:

- { name: pgcrypto ,schema: extensions } # cryptographic functions

- { name: pg_net ,schema: extensions } # async HTTP

- { name: pgjwt ,schema: extensions } # json web token API for postgres

- { name: uuid-ossp ,schema: extensions } # generate universally unique identifiers (UUIDs)

- { name: pgsodium } # pgsodium is a modern cryptography library for Postgres.

- { name: supabase_vault } # Supabase Vault Extension

- { name: pg_graphql } # pg_graphql: GraphQL support

- { name: pg_jsonschema } # pg_jsonschema: Validate json schema

- { name: wrappers } # wrappers: FDW collections

- { name: http } # http: allows web page retrieval inside the database.

- { name: pg_cron } # pg_cron: Job scheduler for PostgreSQL

- { name: timescaledb } # timescaledb: Enables scalable inserts and complex queries for time-series data

- { name: pg_tle } # pg_tle: Trusted Language Extensions for PostgreSQL

- { name: vector } # pgvector: the vector similarity search

- { name: pgmq } # pgmq: A lightweight message queue like AWS SQS and RSMQ

# supabase required extensions

pg_libs: 'timescaledb, plpgsql, plpgsql_check, pg_cron, pg_net, pg_stat_statements, auto_explain, pg_tle, plan_filter'

pg_parameters:

cron.database_name: postgres

pgsodium.enable_event_trigger: off

pg_hba_rules: # supabase hba rules, require access from docker network

- { user: all ,db: postgres ,addr: intra ,auth: pwd ,title: 'allow supabase access from intranet' }

- { user: all ,db: postgres ,addr: 172.17.0.0/16 ,auth: pwd ,title: 'allow access from local docker network' }

node_crontab: [ '00 01 * * * postgres /pg/bin/pg-backup full' ] # make a full backup every 1am

#==============================================================#

# Global Parameters

#==============================================================#

vars:

version: v3.5.0 # pigsty version string

admin_ip: 10.10.10.10 # admin node ip address

region: default # upstream mirror region: default|china|europe

node_tune: oltp # node tuning specs: oltp,olap,tiny,crit

pg_conf: oltp.yml # pgsql tuning specs: {oltp,olap,tiny,crit}.yml

docker_enabled: true # enable docker on app group

#docker_registry_mirrors: ["https://docker.1ms.run"] # use mirror in mainland china

proxy_env: # global proxy env when downloading packages & pull docker images

no_proxy: "localhost,127.0.0.1,10.0.0.0/8,192.168.0.0/16,*.pigsty,*.aliyun.com,mirrors.*,*.tsinghua.edu.cn"

#http_proxy: 127.0.0.1:12345 # add your proxy env here for downloading packages or pull images

#https_proxy: 127.0.0.1:12345 # usually the proxy is format as http://user:[email protected]

#all_proxy: 127.0.0.1:12345

certbot_email: [email protected] # your email address for applying free let's encrypt ssl certs

infra_portal: # domain names and upstream servers

home : { domain: h.pigsty }

grafana : { domain: g.pigsty ,endpoint: "${admin_ip}:3000" , websocket: true }

prometheus : { domain: p.pigsty ,endpoint: "${admin_ip}:9090" }

alertmanager : { domain: a.pigsty ,endpoint: "${admin_ip}:9093" }

minio : { domain: m.pigsty ,endpoint: "10.10.10.10:9001", https: true, websocket: true }

blackbox : { endpoint: "${admin_ip}:9115" }

loki : { endpoint: "${admin_ip}:3100" } # expose supa studio UI and API via nginx

supa : # nginx server config for supabase

domain: supa.pigsty # REPLACE WITH YOUR OWN DOMAIN!

endpoint: "10.10.10.10:8000" # supabase service endpoint: IP:PORT

websocket: true # add websocket support

certbot: supa.pigsty # certbot cert name, apply with `make cert`

#----------------------------------#

# Credential: CHANGE THESE PASSWORDS

#----------------------------------#

#grafana_admin_username: admin

grafana_admin_password: pigsty

#pg_admin_username: dbuser_dba

pg_admin_password: DBUser.DBA

#pg_monitor_username: dbuser_monitor

pg_monitor_password: DBUser.Monitor

#pg_replication_username: replicator

pg_replication_password: DBUser.Replicator

#patroni_username: postgres

patroni_password: Patroni.API

#haproxy_admin_username: admin

haproxy_admin_password: pigsty

#minio_access_key: minioadmin

minio_secret_key: minioadmin # minio root secret key, `minioadmin` by default, also change pgbackrest_repo.minio.s3_key_secret

# use minio as supabase file storage, single node single driver mode for demonstration purpose

minio_buckets: [ { name: pgsql }, { name: supa } ]

minio_users:

- { access_key: dba , secret_key: S3User.DBA, policy: consoleAdmin }

- { access_key: pgbackrest , secret_key: S3User.Backup, policy: readwrite }

- { access_key: supabase , secret_key: S3User.Supabase, policy: readwrite }

minio_endpoint: https://sss.pigsty:9000 # explicit overwrite minio endpoint with haproxy port

node_etc_hosts: ["10.10.10.10 sss.pigsty"] # domain name to access minio from all nodes (required)

# use minio as default backup repo for PostgreSQL

pgbackrest_method: minio # pgbackrest repo method: local,minio,[user-defined...]

pgbackrest_repo: # pgbackrest repo: https://pgbackrest.org/configuration.html#section-repository

local: # default pgbackrest repo with local posix fs

path: /pg/backup # local backup directory, `/pg/backup` by default

retention_full_type: count # retention full backups by count

retention_full: 2 # keep 2, at most 3 full backup when using local fs repo

minio: # optional minio repo for pgbackrest

type: s3 # minio is s3-compatible, so s3 is used

s3_endpoint: sss.pigsty # minio endpoint domain name, `sss.pigsty` by default

s3_region: us-east-1 # minio region, us-east-1 by default, useless for minio

s3_bucket: pgsql # minio bucket name, `pgsql` by default

s3_key: pgbackrest # minio user access key for pgbackrest

s3_key_secret: S3User.Backup # minio user secret key for pgbackrest <------------------ HEY, DID YOU CHANGE THIS?

s3_uri_style: path # use path style uri for minio rather than host style

path: /pgbackrest # minio backup path, default is `/pgbackrest`

storage_port: 9000 # minio port, 9000 by default

storage_ca_file: /etc/pki/ca.crt # minio ca file path, `/etc/pki/ca.crt` by default

block: y # Enable block incremental backup

bundle: y # bundle small files into a single file

bundle_limit: 20MiB # Limit for file bundles, 20MiB for object storage

bundle_size: 128MiB # Target size for file bundles, 128MiB for object storage

cipher_type: aes-256-cbc # enable AES encryption for remote backup repo

cipher_pass: pgBackRest # AES encryption password, default is 'pgBackRest' <----- HEY, DID YOU CHANGE THIS?

retention_full_type: time # retention full backup by time on minio repo

retention_full: 14 # keep full backup for last 14 days

pg_version: 17

repo_extra_packages: [pg17-core ,pg17-time ,pg17-gis ,pg17-rag ,pg17-fts ,pg17-olap ,pg17-feat ,pg17-lang ,pg17-type ,pg17-util ,pg17-func ,pg17-admin ,pg17-stat ,pg17-sec ,pg17-fdw ,pg17-sim ,pg17-etl ]

pg_extensions: [ pg17-time ,pg17-gis ,pg17-rag ,pg17-fts ,pg17-feat ,pg17-lang ,pg17-type ,pg17-util ,pg17-func ,pg17-admin ,pg17-stat ,pg17-sec ,pg17-fdw ,pg17-sim ,pg17-etl, pg_mooncake, pg_analytics, pg_parquet ] #,pg17-olap]

For advanced topics, we may need to modify the configuration file to fit our needs.

- Security Enhancement

- Domain Name and HTTPS

- Sending Mail with SMTP

- MinIO or External S3

- True High Availability

Security Enhancement

For security reasons, you should change the default passwords in the pigsty.yml config file.

grafana_admin_password:pigsty, Grafana admin passwordpg_admin_password:DBUser.DBA, PGSQL superuser passwordpg_monitor_password:DBUser.Monitor, PGSQL monitor user passwordpg_replication_password:DBUser.Replicator, PGSQL replication user passwordpatroni_password:Patroni.API, Patroni HA Agent Passwordhaproxy_admin_password:pigsty, Load balancer admin passwordminio_access_key:minioadmin, MinIO root usernameminio_secret_key:minioadmin, MinIO root password

Supabase will use PostgreSQL & MinIO as its backend, so also change the following passwords for supabase business users:

pg_users: password for supabase business users in postgresminio_users:minioadmin, MinIO business user’s password

The pgbackrest will take backups and WALs to MinIO, so also change the following passwords reference

pgbackrest_repo: refer to the

PLEASE check the Supabase Self-Hosting: Generate API Keys to generate supabase credentials:

jwt_secret: a secret key with at least 40 charactersanon_key: a jwt token generate for anonymous users, based onjwt_secretservice_role_key: a jwt token generate for elevated service roles, based onjwt_secretdashboard_username: supabase studio web portal username,supabaseby defaultdashboard_password: supabase studio web portal password,pigstyby default

If you have chanaged the default password for PostgreSQL and MinIO, you have to update the following parameters as well:

postgres_password, according topg_userss3_access_keyands3_secret_key, according tominio_users

Domain Name and HTTPS

For local or intranet use, you can connect directly to Kong port on http://<IP>:8000 or 8443 for https.

This works but isn’t ideal. Using a domain with HTTPS is strongly recommended when serving Supabase to the public.

Pigsty has a Nginx server installed & configured on the admin node to act as a reverse proxy for all web based service.

which is configured via the infra_portal parameter.

all:

vars:

infra_portal:

supa :

domain: supa.pigsty.cc # replace the default supa.pigsty domain name with your own domain name

endpoint: "10.10.10.10:8000"

websocket: true

certbot: supa.pigsty.cc # certificate name, usually the same as the domain name

On the client side, you can use the domain supa.pigsty to access the Supabase Studio management interface.

You can add this domain to your local /etc/hosts file or use a local DNS server to resolve it to the server’s external IP address.

To use a real domain with HTTPS, you will need to modify the all.vars.infra_portal.supa with updated domain name (such as supa.pigsty.cc here).

You can obtain a free HTTPS certificate with certbot as simple as:

make cert

You also have to update the all.children.supa.apps.supabase.conf to tell supabase to use the new domain name:

all:

children: # clusters

supa:

vars:

apps:

supabase:

conf:

SITE_URL: https://supa.pigsty.cc # <------- Change This to your external domain name

API_EXTERNAL_URL: https://supa.pigsty.cc # <------- Otherwise the storage api may not work!

SUPABASE_PUBLIC_URL: https://supa.pigsty.cc # <------- DO NOT FORGET TO PUT IT IN infra_portal!

And reload the supabase service to apply the new configuration:

./app.yml -t app_config,app_launch # reload supabase config

Sending Mail with SMTP

Some Supabase features require email. For production use, I’d recommend using an external SMTP service. Since self-hosted SMTP servers often result in rejected or spam-flagged emails.

To do this, modify the Supabase configuration and add SMTP credentials:

all:

children: # clusters

supa:

vars:

apps:

supabase:

conf:

SMTP_HOST: smtpdm.aliyun.com:80

SMTP_PORT: 80

SMTP_USER: [email protected]

SMTP_PASS: your_email_user_password

SMTP_SENDER_NAME: MySupabase

SMTP_ADMIN_EMAIL: [email protected]

ENABLE_ANONYMOUS_USERS: false

And don’t forget to reload the supabase service with app.yml -t app_config,app_launch

MinIO or External S3

Pigsty’s self-hosting supabase will use a local SNSD MinIO server, which is used by Supabase itself for object storage, and by PostgreSQL for backups. For production use, you should consider using a HA MNMD MinIO cluster or an external S3 compatible service instead.

We recommend using an external S3 when:

- you just have one single server available, then external s3 gives you a minimal disaster recovery guarantee, with RTO in hours and RPO in MBs.

- you are operating in the cloud, then using S3 directly is recommended rather than wrap expensively EBS with MinIO

The

terraform/spec/aliyun-meta-s3.tfprovides an example of how to provision a single node alone with an S3 bucket.

To use an external S3 compatible service, you’ll have to update two related references in the pigsty.yml config.

For example, to use Aliyun OSS as the object storage for Supabase, you can modify the all.children.supabase.vars.supa_config to point to the Aliyun OSS bucket:

all:

children:

supabase:

vars:

supa_config:

s3_bucket: pigsty-oss

s3_endpoint: https://oss-cn-beijing-internal.aliyuncs.com

s3_access_key: xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

s3_secret_key: xxxxxxxxxxxxxxxx

s3_force_path_style: false

s3_protocol: https

s3_region: oss-cn-beijing

Reload the supabase service with ./supabase.yml -t supa_config,supa_launch again.

The next reference is in the PostgreSQL backup repo:

all:

vars:

# use minio as default backup repo for PostgreSQL

pgbackrest_method: minio # pgbackrest repo method: local,minio,[user-defined...]

pgbackrest_repo: # pgbackrest repo: https://pgbackrest.org/configuration.html#section-repository

local: # default pgbackrest repo with local posix fs

path: /pg/backup # local backup directory, `/pg/backup` by default

retention_full_type: count # retention full backups by count

retention_full: 2 # keep 2, at most 3 full backup when using local fs repo

minio: # optional minio repo for pgbackrest

type: s3 # minio is s3-compatible, so s3 is used

# update your credentials here

s3_endpoint: oss-cn-beijing-internal.aliyuncs.com

s3_region: oss-cn-beijing

s3_bucket: pigsty-oss

s3_key: xxxxxxxxxxxxxx

s3_key_secret: xxxxxxxx

s3_uri_style: host

path: /pgbackrest # minio backup path, default is `/pgbackrest`

storage_port: 9000 # minio port, 9000 by default

storage_ca_file: /pg/cert/ca.crt # minio ca file path, `/pg/cert/ca.crt` by default

bundle: y # bundle small files into a single file

cipher_type: aes-256-cbc # enable AES encryption for remote backup repo

cipher_pass: pgBackRest # AES encryption password, default is 'pgBackRest'

retention_full_type: time # retention full backup by time on minio repo

retention_full: 14 # keep full backup for last 14 days

After updating the pgbackrest_repo, you can reset the pgBackrest backup with ./pgsql.yml -t pgbackrest.

True High Availability

The default single-node deployment (with external S3) provide a minimal disaster recovery guarantee, with RTO in hours and RPO in MBs.

To achieve RTO < 30s and zero data loss, you need a multi-node high availability cluster with at least 3-nodes.

Which involves high availability for these components:

- ETCD: DCS requires at least three nodes to tolerate one node failure.

- PGSQL: PGSQL synchronous commit mode recommends at least three nodes.

- INFRA: It’s good to have two or three copies of observability stack.

- Supabase itself can also have multiple replicas to achieve high availability.

We recommend you to refer to the trio and safe config to upgrade your cluster to three nodes or more.

In this case, you also need to modify the access points for PostgreSQL and MinIO to use the DNS / L2 VIP / HAProxy HA access points.

all:

children:

supabase:

hosts:

10.10.10.10: { supa_seq: 1 }

10.10.10.11: { supa_seq: 2 }

10.10.10.12: { supa_seq: 3 }

vars:

supa_cluster: supa # cluster name

supa_config:

postgres_host: 10.10.10.2 # use the PG L2 VIP

postgres_port: 5433 # use the 5433 port to access the primary instance through pgbouncer

s3_endpoint: https://sss.pigsty:9002 # If you are using MinIO through the haproxy lb port 9002

minio_domain_ip: 10.10.10.3 # use the L2 VIP binds to all proxy nodes

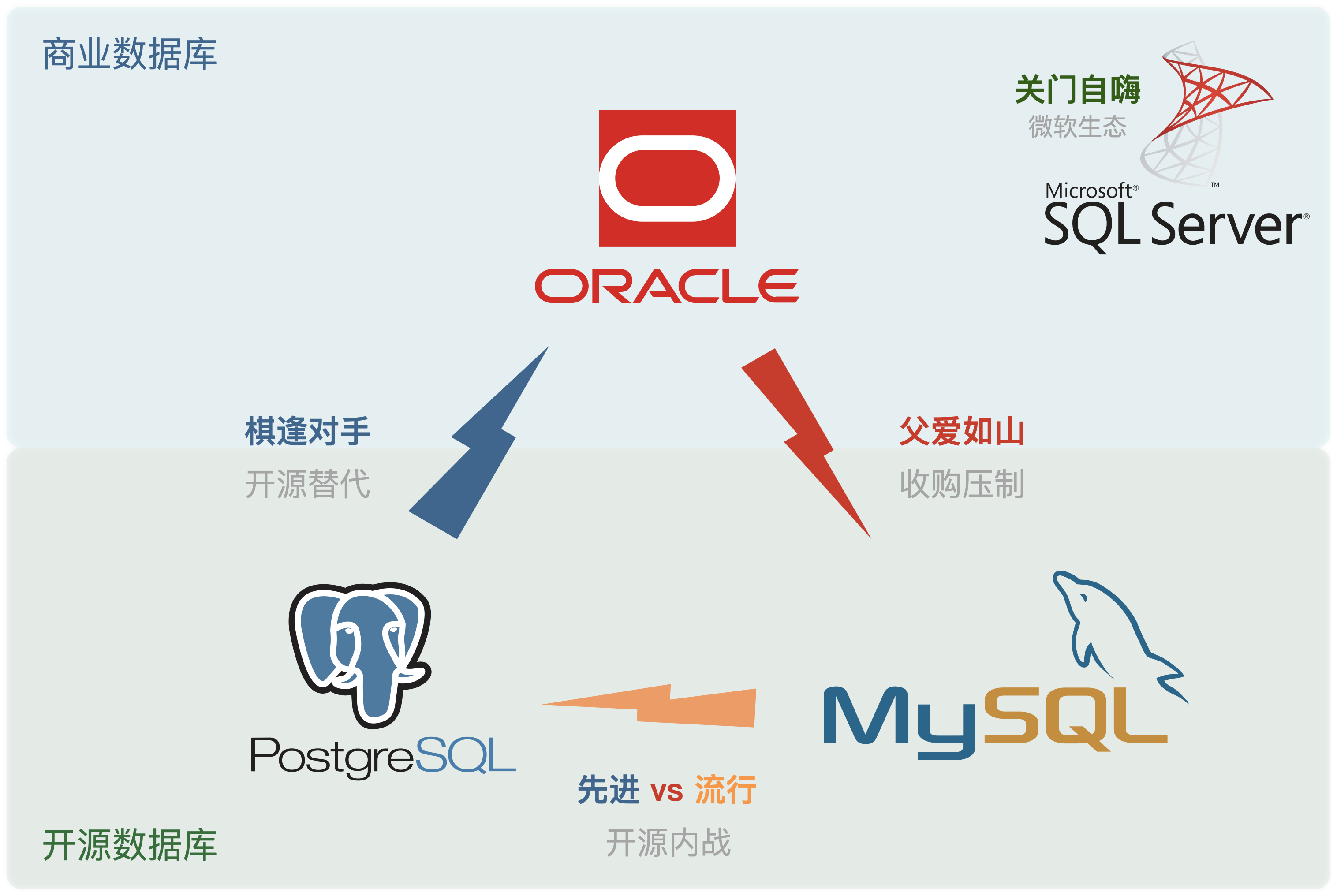

MySQL is dead, Long live PostgreSQL!

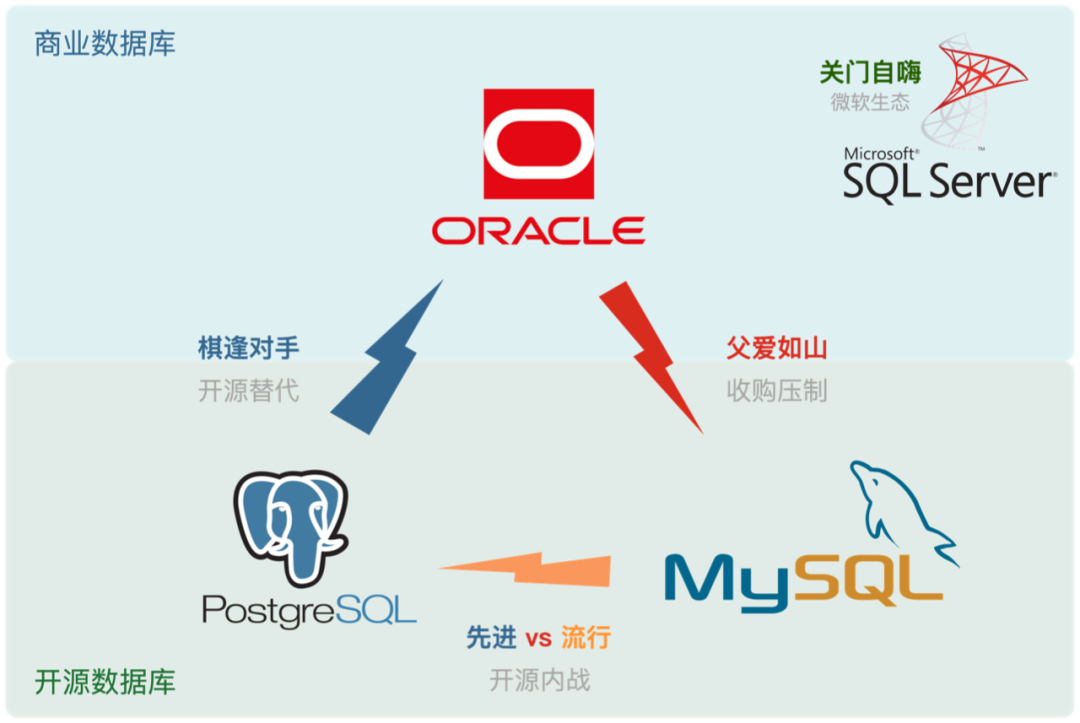

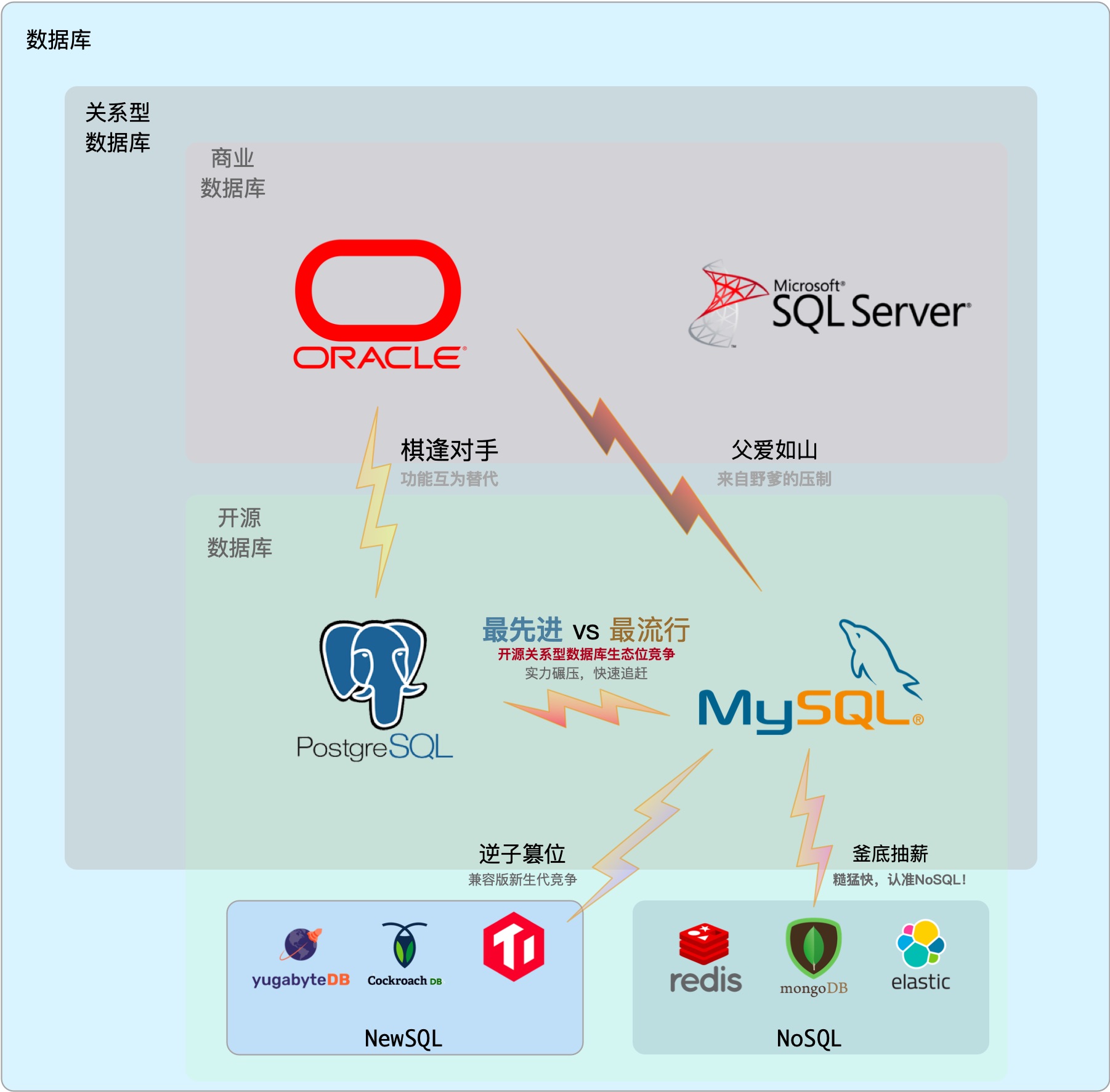

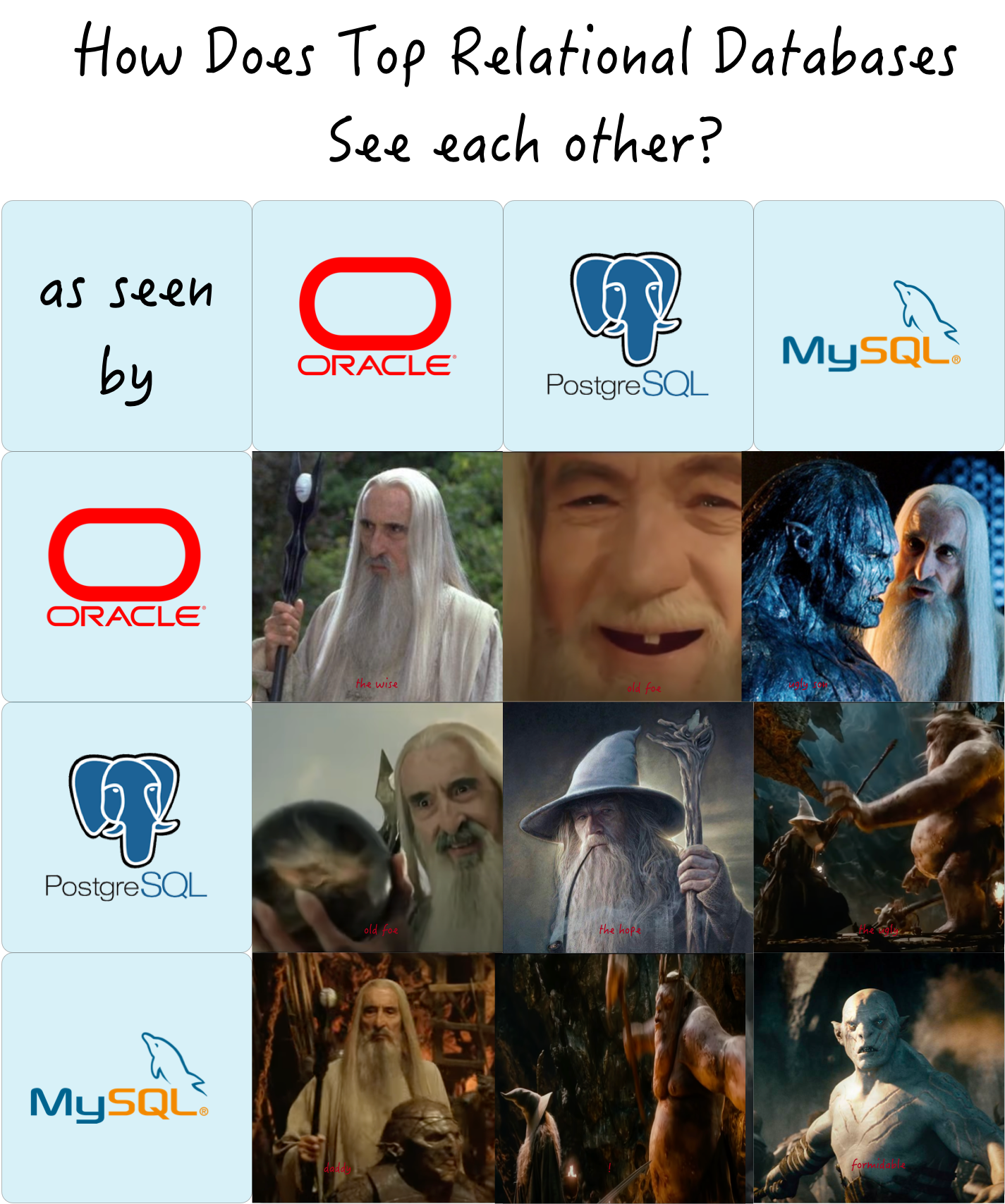

This July, MySQL 9.0 was finally released—a full eight years after its last major version, 8.0 (@2016-09). Yet, this hollow “innovation” release feels like a bad joke, signaling that MySQL is on its deathbed.

While PostgreSQL continues to surge ahead, MySQL’s sunset is painfully acknowledged by Percona, a major flag-bearer of the MySQL ecosystem, through a series of poignant posts: “Where is MySQL Heading?”, “Did Oracle Finally Kill MySQL?”, and “Can Oracle Save MySQL?”, openly expressing disappointment and frustration with MySQL.

Peter Zaitsev, CEO of Percona, remarked:

Who needs MySQL when there’s PostgreSQL? But if MySQL dies, PostgreSQL might just monopolize the database world, so at least MySQL can serve as a whetstone for PostgreSQL to reach its zenith.

Some databases are eating the DBMS world, while others are fading into obscurity.

MySQL is dead, Long live PostgreSQL!

- Hollow Innovations

- Sloppy Vector Types

- Belated JavaScript Functions

- Lagging Features

- Degrading Performance

- Irredeemable Isolation Levels

- Shrinking Ecosystem

- Who Really Killed MySQL?

- PostgreSQL Ascends as MySQL Rests in Peace

Hollow Innovations

The official MySQL website’s “What’s New in MySQL 9.0” introduces a few new features of version 9.0, with six features.

And that’s it? That’s all there is?

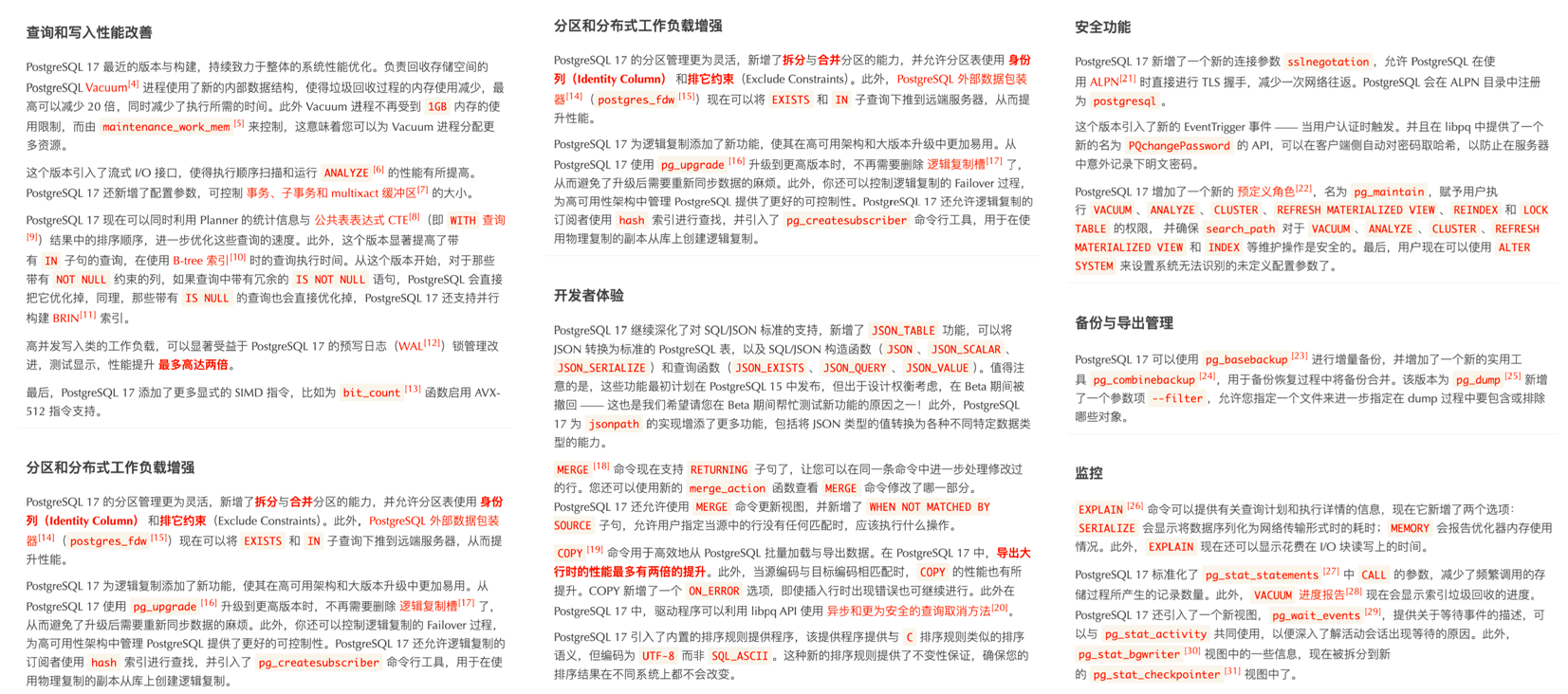

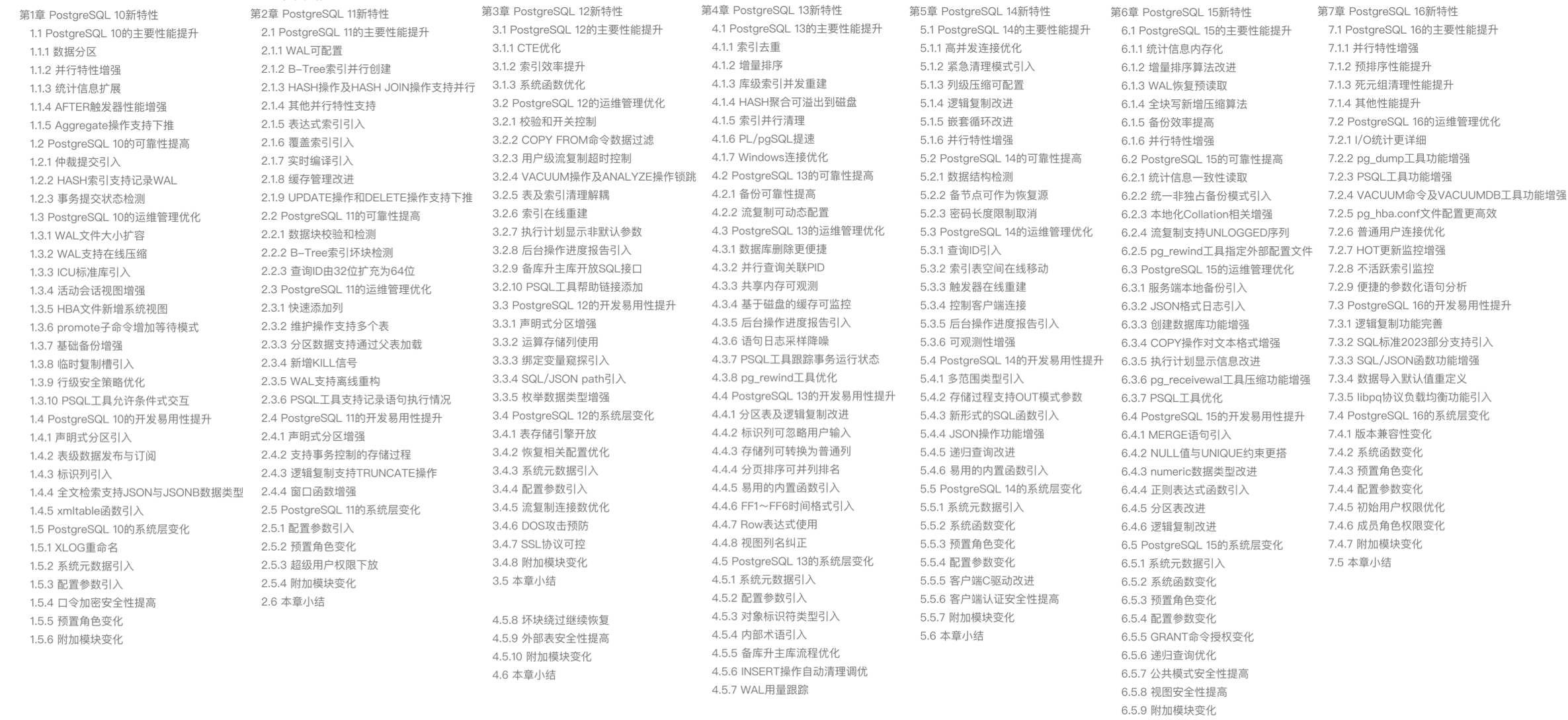

This is surprisingly underwhelming because PostgreSQL’s major releases every year brim with countless new features. For instance, PostgreSQL 17, slated for release this fall, already boasts an impressive list of new features, even though it’s just in beta1:

The recent slew of PostgreSQL features could even fill a book, as seen in “Quickly Mastering New PostgreSQL Features”, which covers the key enhancements from the last seven years, packing the contents to the brim:

Looking back at MySQL’s update, the last four of the six touted features are mere minor patches, barely worth mentioning. The first two—vector data types and JavaScript stored procedures—are supposed to be the highlights.

BUT —

MySQL 9.0’s vector data types are just an alias of BLOB — with a simple array length function added. This kind of feature was supported by PostgreSQL when it was born 28 years ago.

And MySQL’s support for JavaScript stored procedures? It’s an enterprise-only feature—not available in the open-source version, while PostgreSQL has had this capability since 13 years ago with version 9.1.

After an eight-year wait, the “innovative update” delivers two “old features,” one of which is gated behind an enterprise edition. The term “innovation” here seems bitterly ironic and sarcastic.

Sloppy Vector Types

In the past few years, AI has exploded in popularity, boosting interest in vector databases. Nearly every mainstream DBMS now supports vector data types—except for MySQL.

Users might have hoped that MySQL 9.0, touted as an innovative release, would fill some gaps in this area. Instead, they were greeted with a shocking level of complacency—how could they be so sloppy?

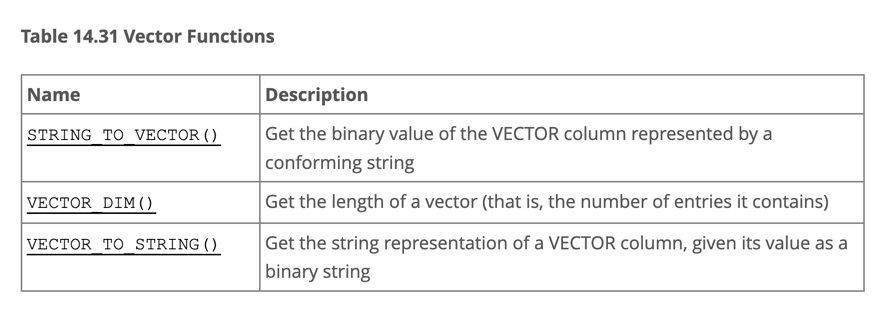

According to MySQL 9.0’s official documentation, there are only three functions related to vector types. Ignoring the two that deal with string conversions, the only real functional command is VECTOR_DIM: it returns the dimension of a vector (i.e., the length of an array)!

The bar for entry into vector databases is not high—a simple vector distance function (think dot product, a 10-line C program, a coding task suitable for elementary students) would suffice. This could enable basic vector retrieval through a full table scan with an ORDER BY d LIMIT n query, representing a minimally viable feature. Yet MySQL 9 didn’t even bother to implement this basic vector distance function, which is not a capability issue but a clear sign that Oracle has lost interest in progressing MySQL. Any seasoned tech observer can see that this so-called “vector type” is merely a BLOBunder a different name—it only manages your binary data input without caring how users want to search or utilize it. Of course, it’s possible Oracle has a more robust version on its MySQL Heatwave, but what’s delivered on MySQL itself is a feature you could hack together in ten minutes.

In contrast, let’s look at PostgreSQL, MySQL’s long-standing rival. Over the past year, the PostgreSQL ecosystem has spawned at least six vector database extensions (pgvector, pgvector.rs, pg_embedding, latern, pase, pgvectorscale) and has reached new heights in a competitive race. The frontrunner, pgvector, which emerged in 2021, quickly reached heights that many specialized vector databases couldn’t, thanks to the collective efforts of developers, vendors, and users standing on PostgreSQL’s shoulders. It could even be argued that pgvector single-handedly ended this niche in databases—“Is the Dedicated Vector Database Era Over?”.

Within this year, pgvector improved its performance by 150 times, and its functionality has dramatically expanded. pgvector offers data types like float vectors, half-precision vectors, bit vectors, and sparse vectors; distance metrics like L1, L2, dot product, Hamming, and Jaccard; various vector and scalar functions and operators; supports IVFFLAT and HNSW vector indexing methods (with the pgvectorscale extension adding DiskANN indexing); supports parallel index building, vector quantization, sparse vector handling, sub-vector indexing, and hybrid retrieval, with potential SIMD instruction acceleration. These rich features, combined with a free open-source license and the collaborative power of the entire PostgreSQL ecosystem, have made pgvector a resounding success. Together with PostgreSQL, it has become the default database for countless AI projects.

Comparing pgvector with MySQL 9’s “vector” support might seem unfair, as MySQL’s offering doesn’t even come close to PostgreSQL’s “multidimensional array type” available since its inception in 1996—at least that had a robust array of functions, not just an array length calculation.

Vectors are the new JSON, but the party at the vector database table has ended, and MySQL hasn’t even managed to serve its dish. It has completely missed the growth engine of the next AI decade, just as it missed the JSON document database wave of the internet era in the previous decade.

Belated JavaScript Functions

Another “blockbuster” feature of MySQL 9.0 is JavaScript Stored Procedures.

However, using JavaScript for stored procedures isn’t a novel concept—back in 2011, PostgreSQL 9.1 could already script JavaScript stored procedures through the plv8 extension, and MongoDB began supporting JavaScript around the same time.

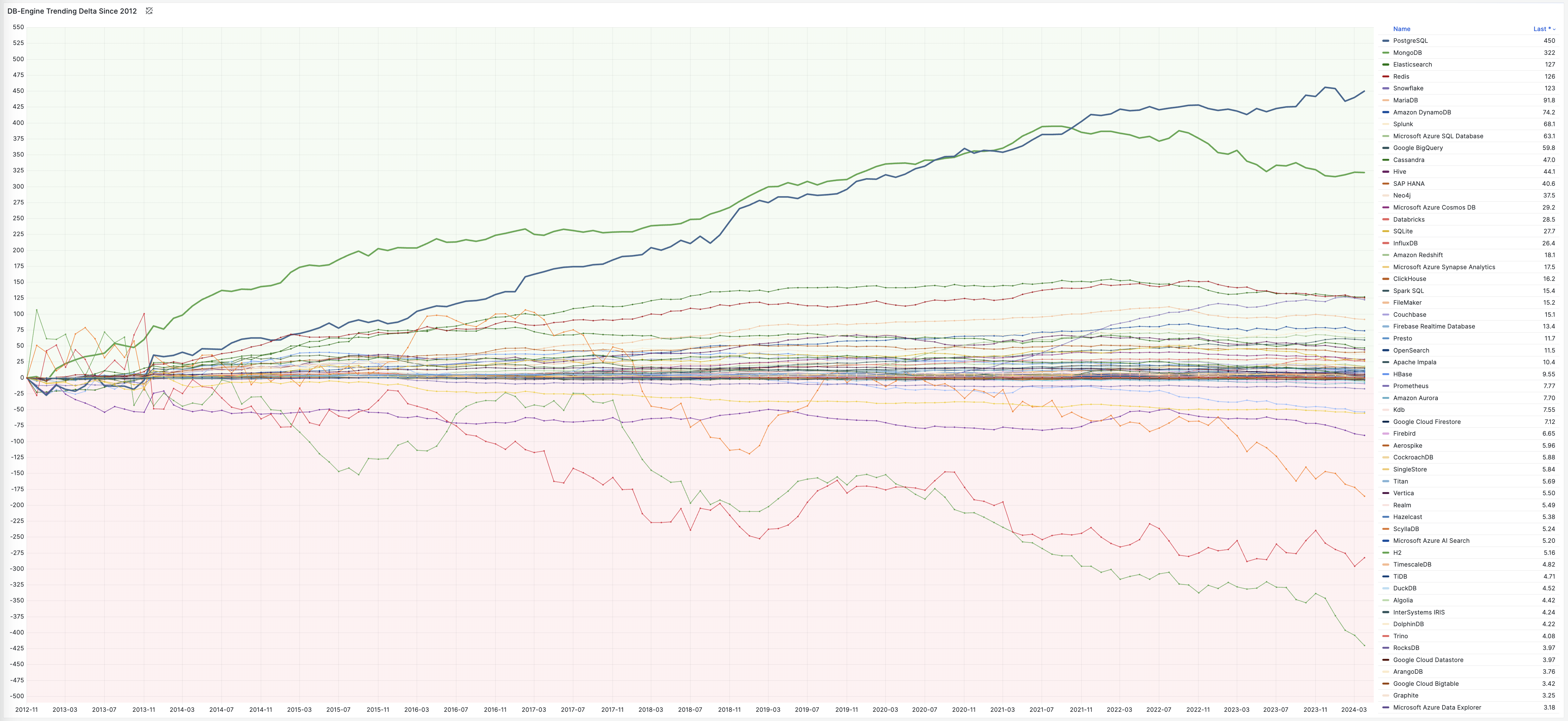

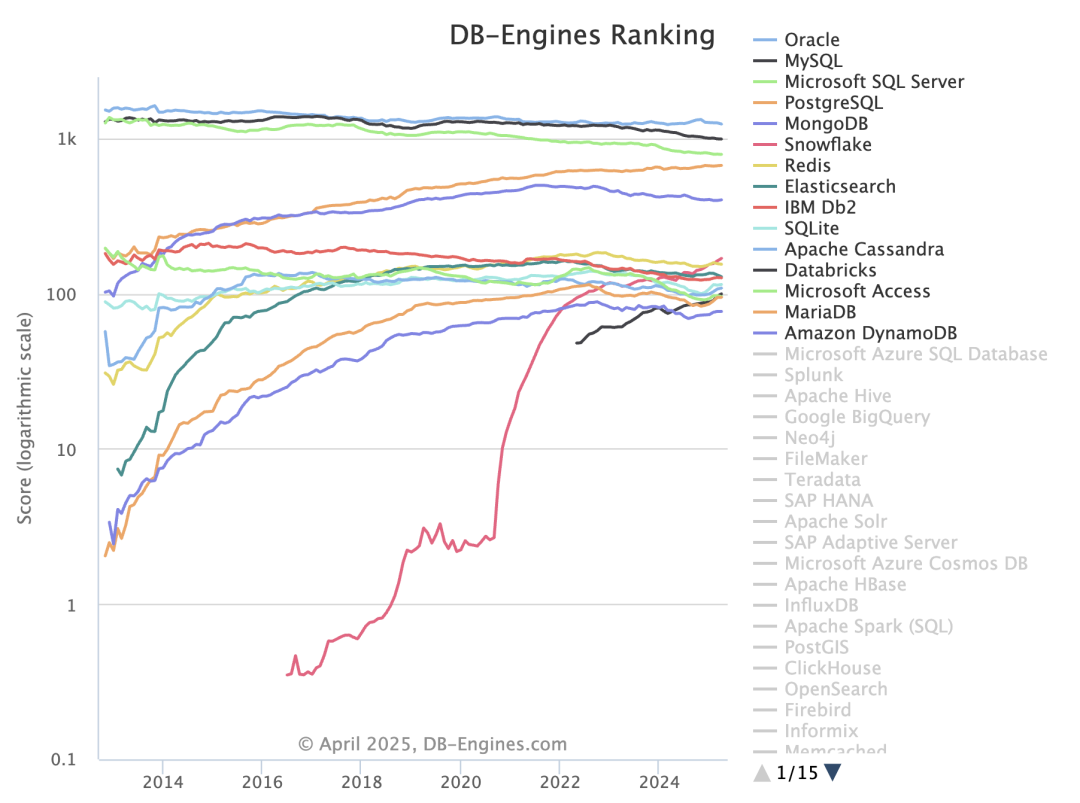

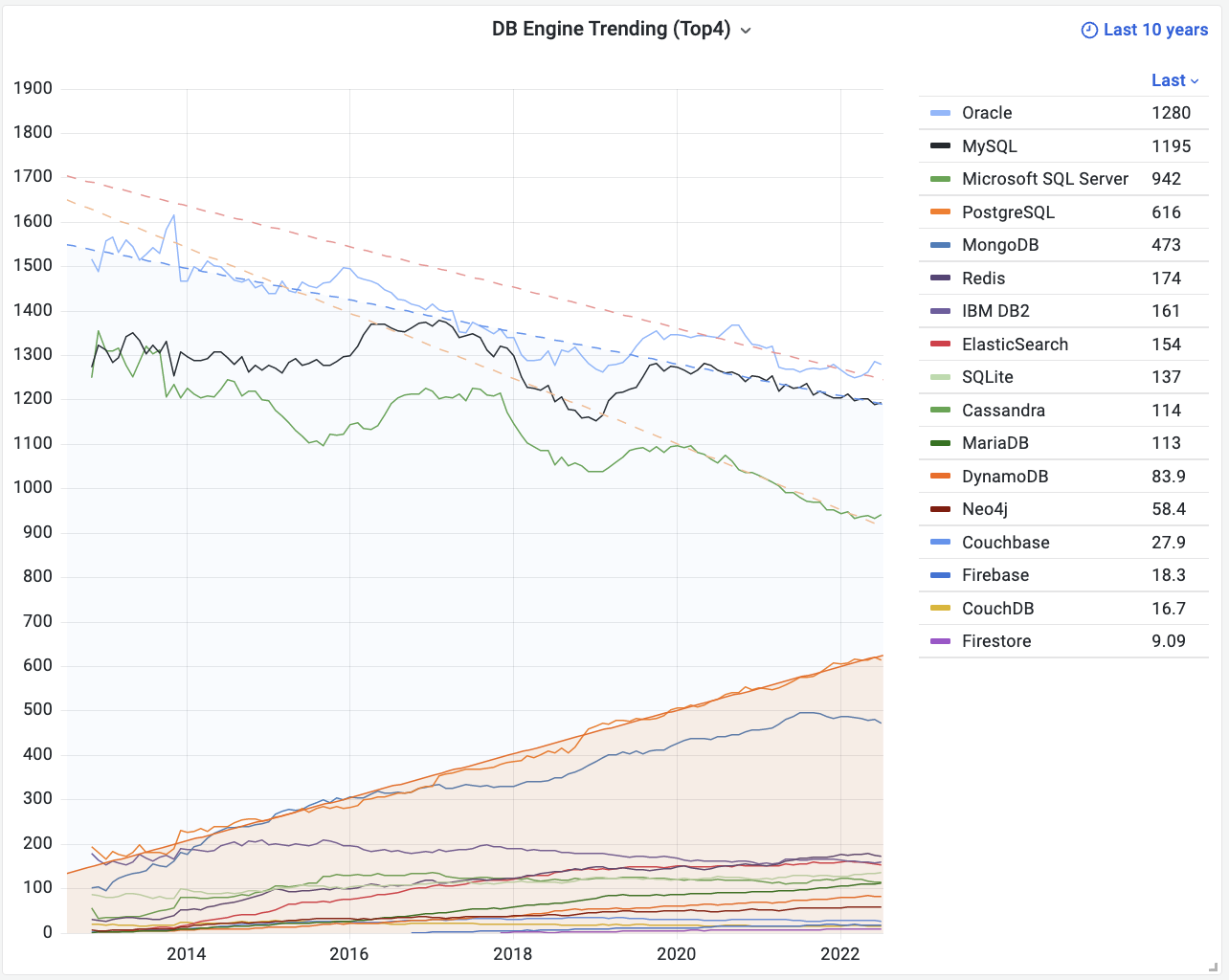

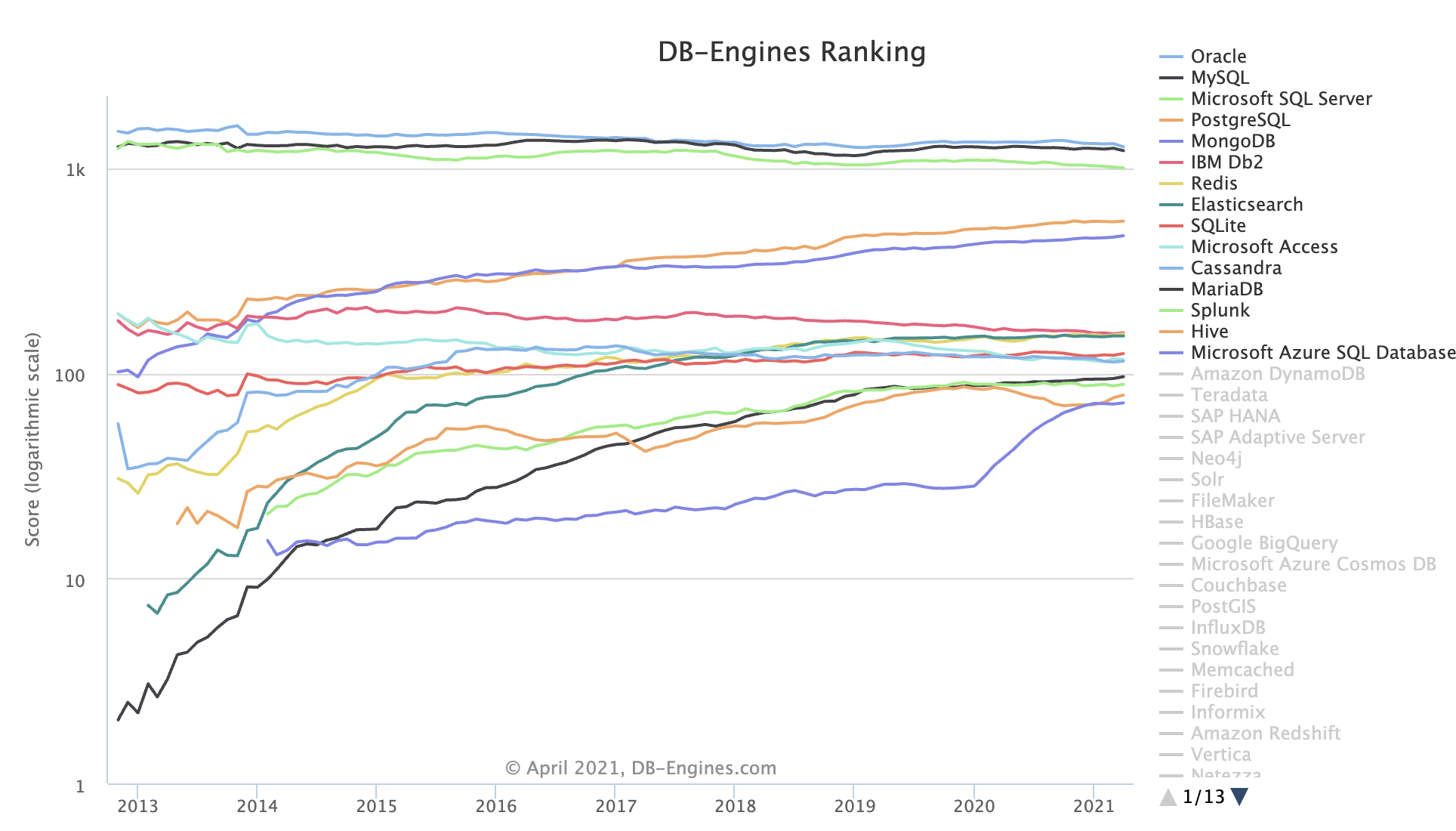

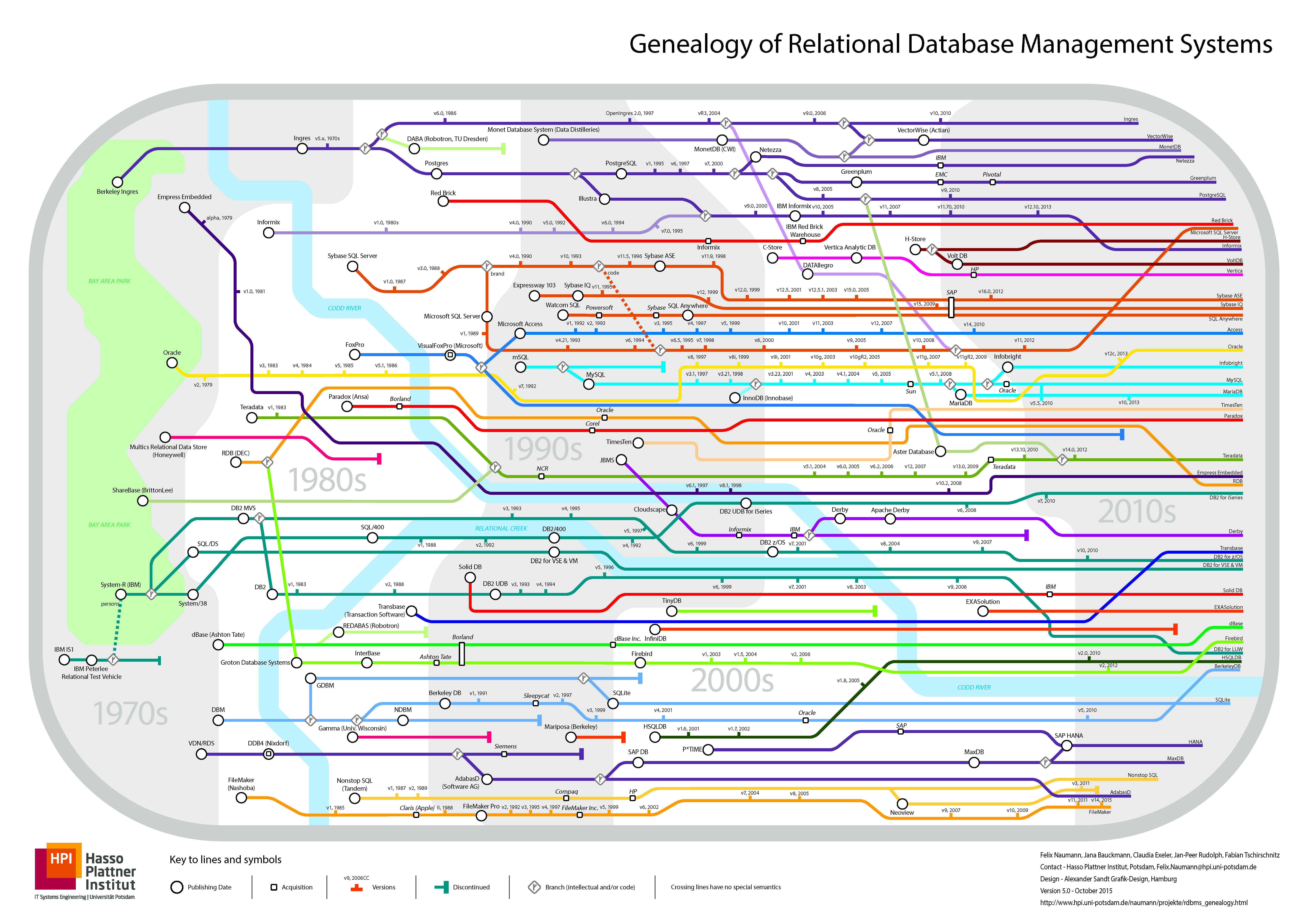

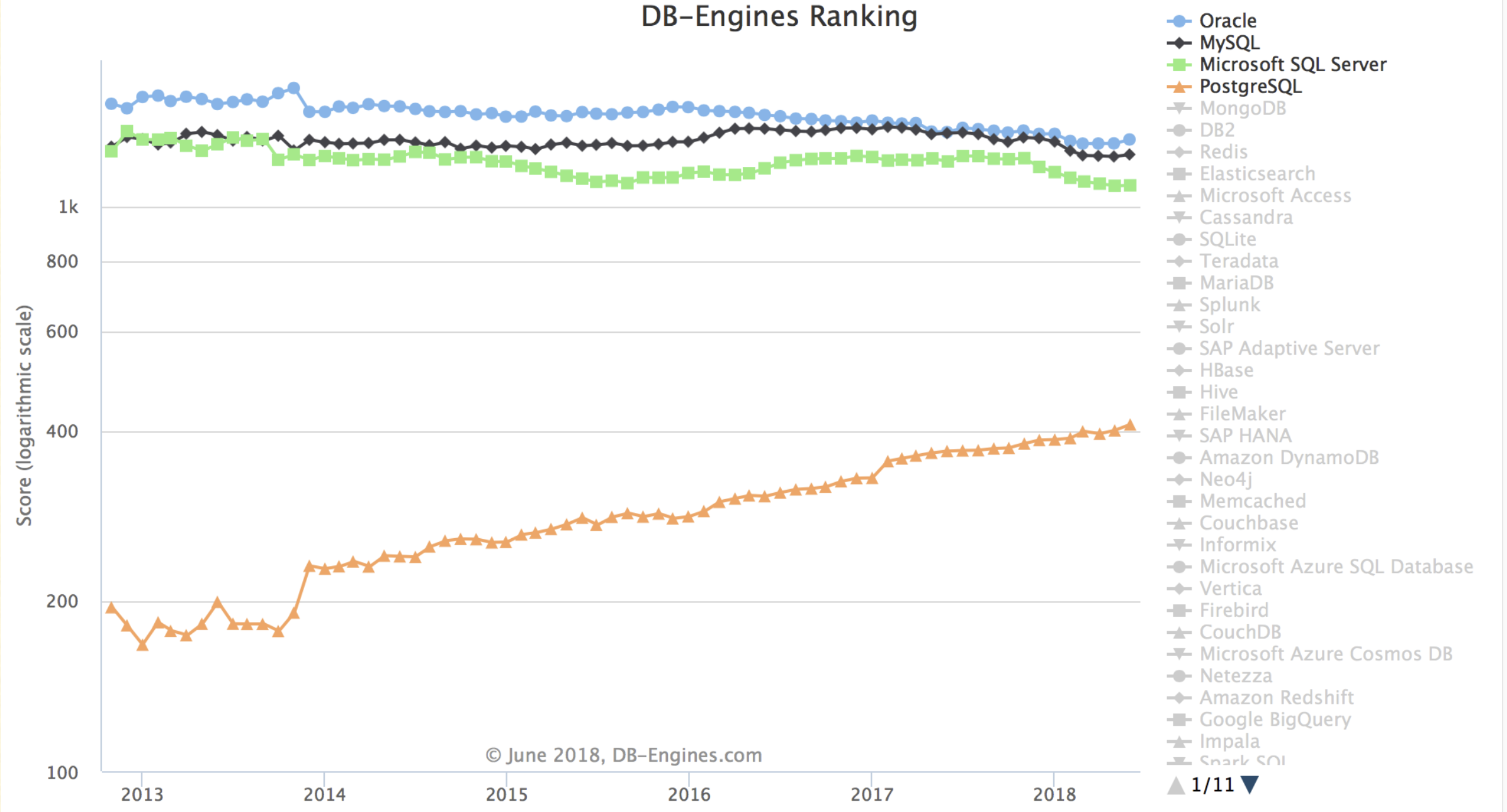

A glance at the past twelve years of the “Database Popularity Trend” on DB-Engine shows that only PostgreSQL and Mongo have truly led the pack. MongoDB (2009) and PostgreSQL 9.2 (2012) were quick to grasp internet developers’ needs, adding JSON feature support (document databases) right as the “Rise of JSON” began, thereby capturing the largest growth share in the database realm over the last decade.

Of course, Oracle, MySQL’s stepfather, added JSON features and JavaScript stored procedure support by the end of 2014 in version 12.1—while MySQL itself unfortunately didn’t catch up until 2024—but it’s too late now!

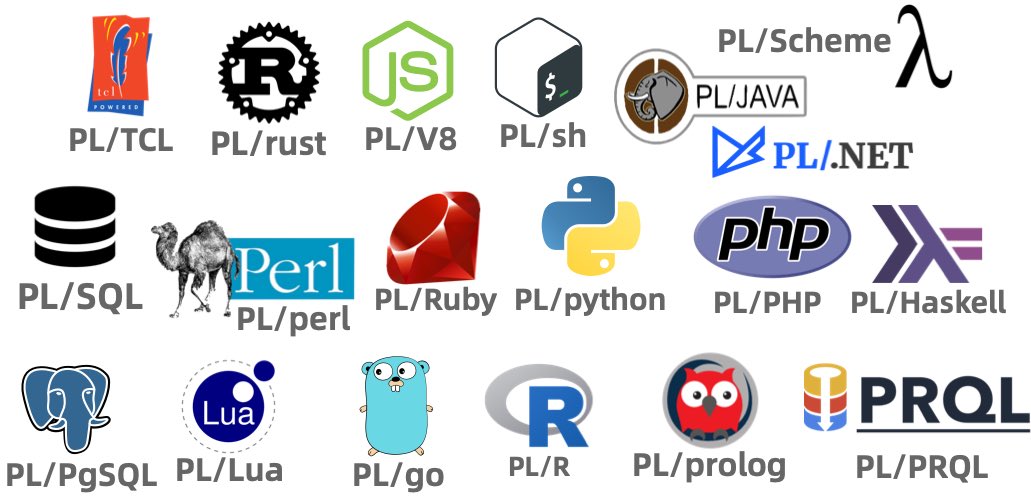

Oracle allows stored procedures to be written in C, SQL, PL/SQL, Python, Java, and JavaScript. But compared to PostgreSQL’s more than twenty supported procedural languages, it’s merely a drop in the bucket:

Unlike PostgreSQL and Oracle’s development philosophy, MySQL’s best practices generally discourage using stored procedures—making JavaScript functions a rather superfluous feature for MySQL. Even so, Oracle made JavaScript stored procedures a MySQL Enterprise Edition exclusive—considering most MySQL users opt for the open-source community version, this feature essentially went unnoticed.

Falling Behind: Features and Flexibility

MySQL’s feature deficiencies go beyond mere programming language and stored procedure support. Across various dimensions, MySQL significantly lags behind its competitor PostgreSQL—not just in core database capabilities but also in its extensibility ecosystem.

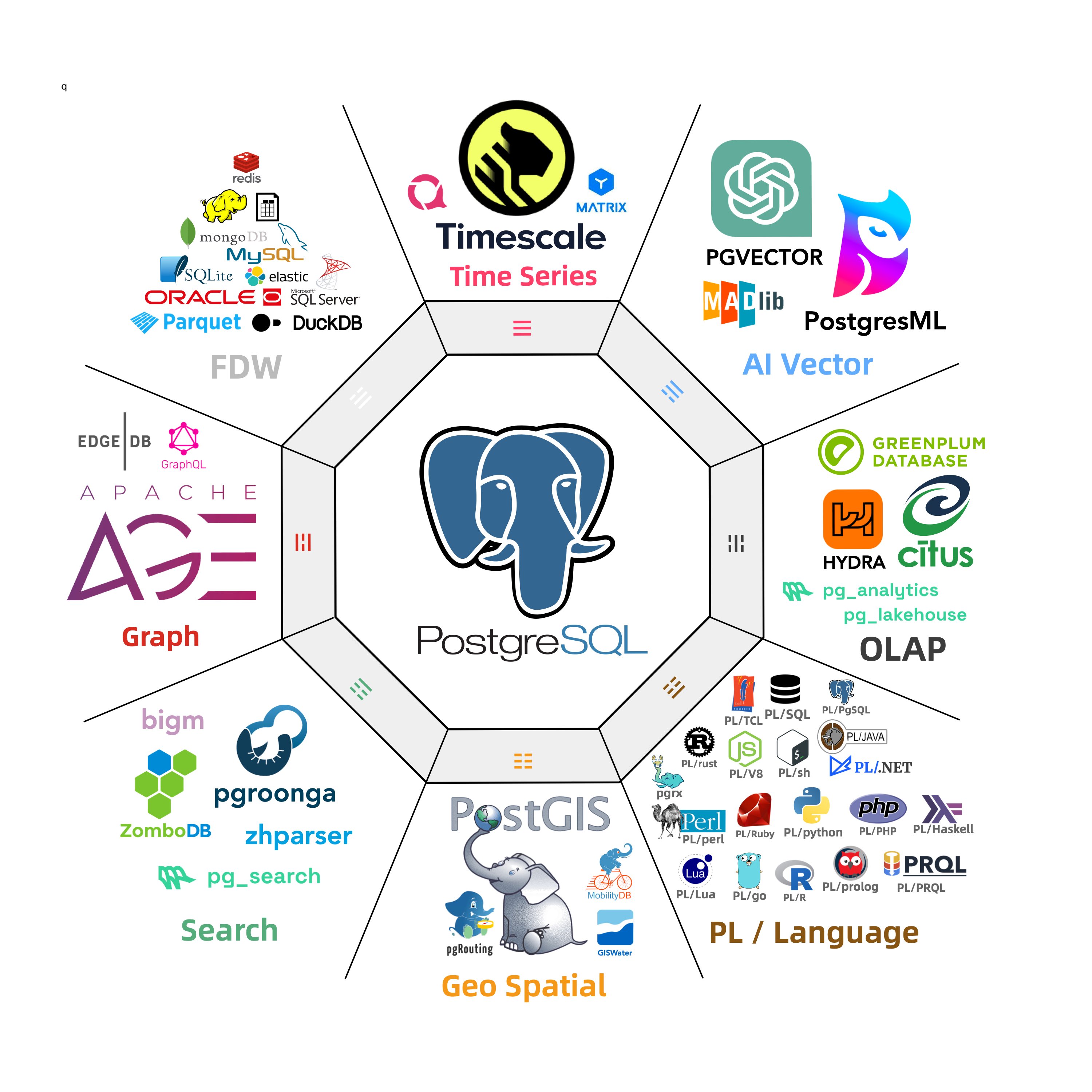

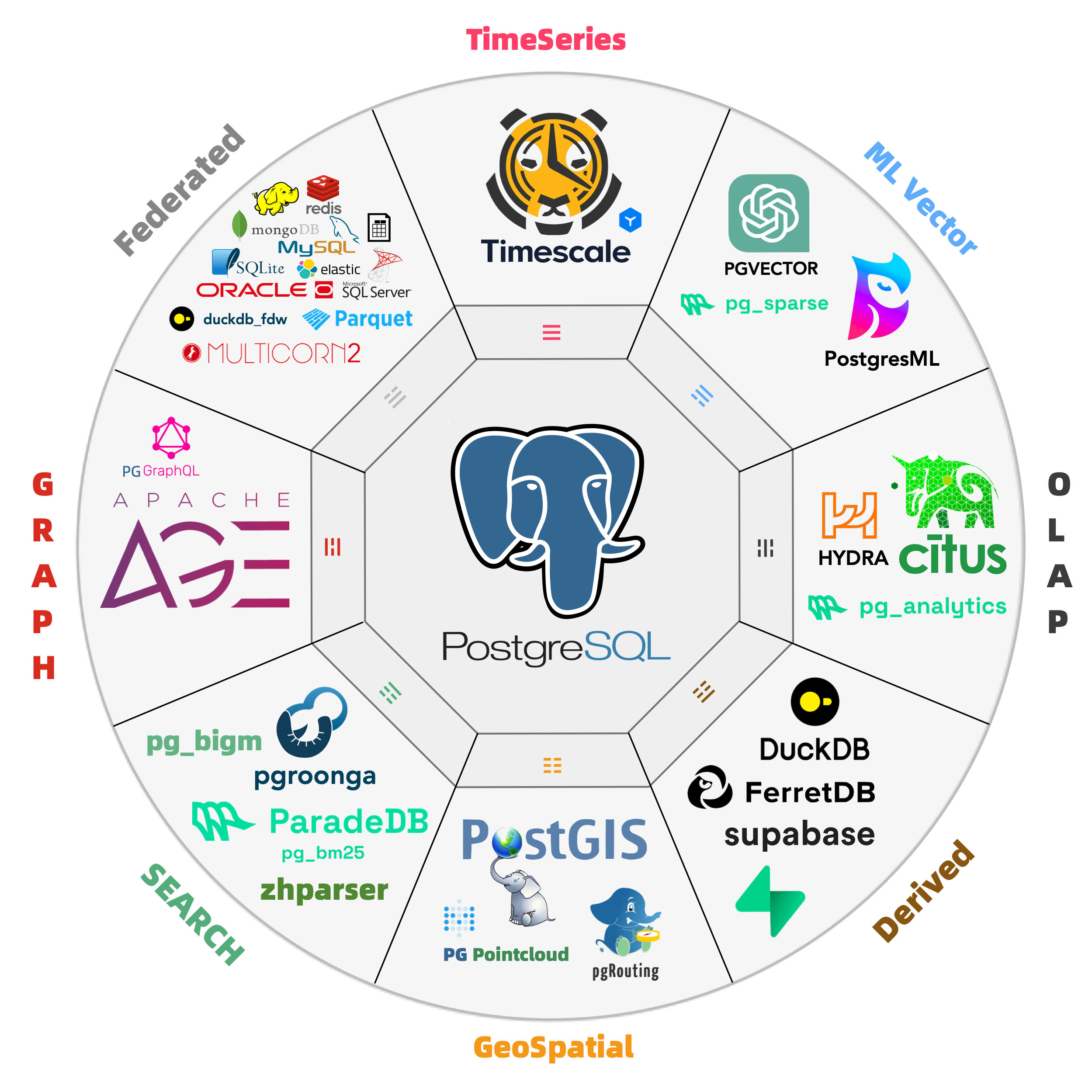

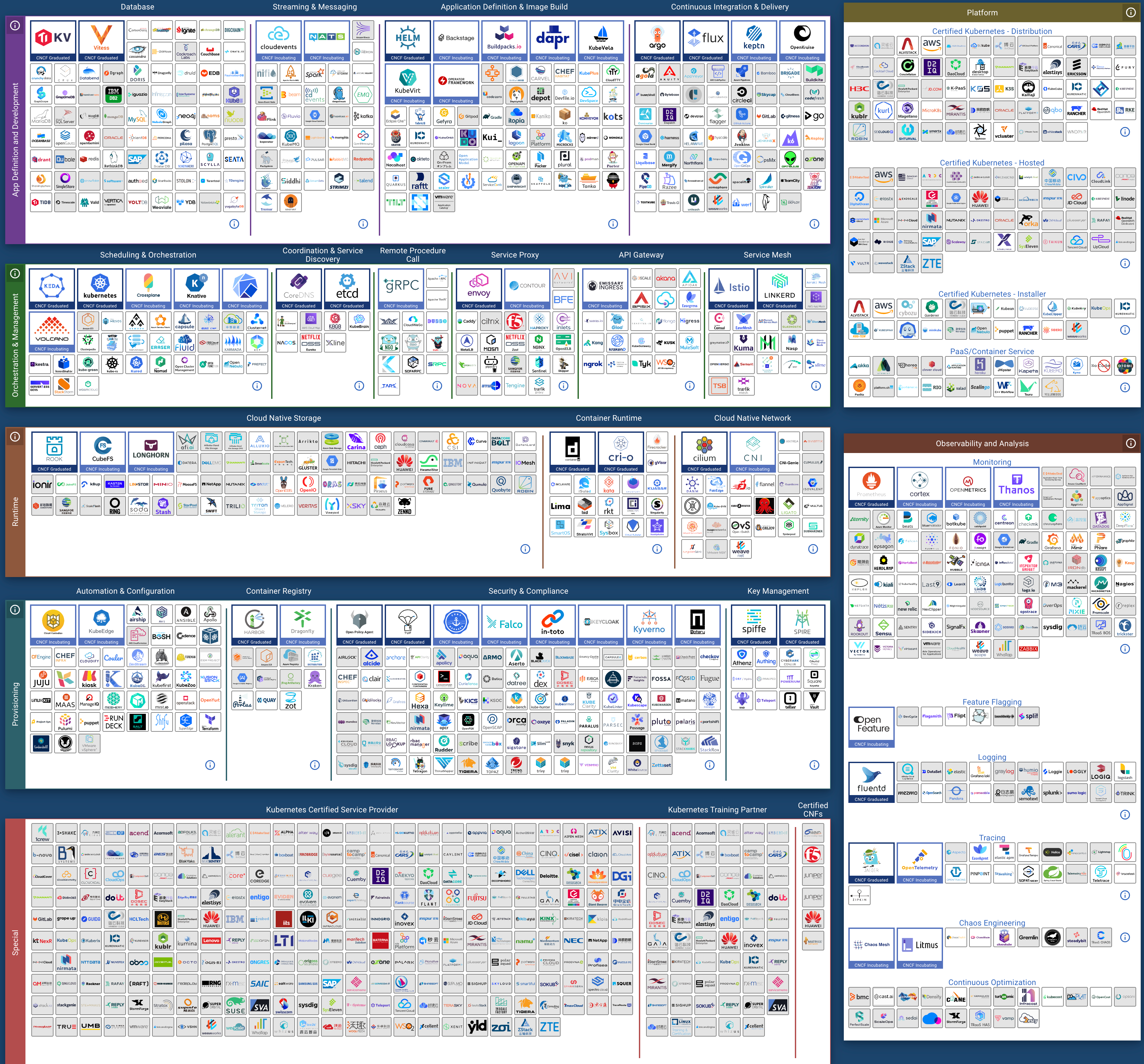

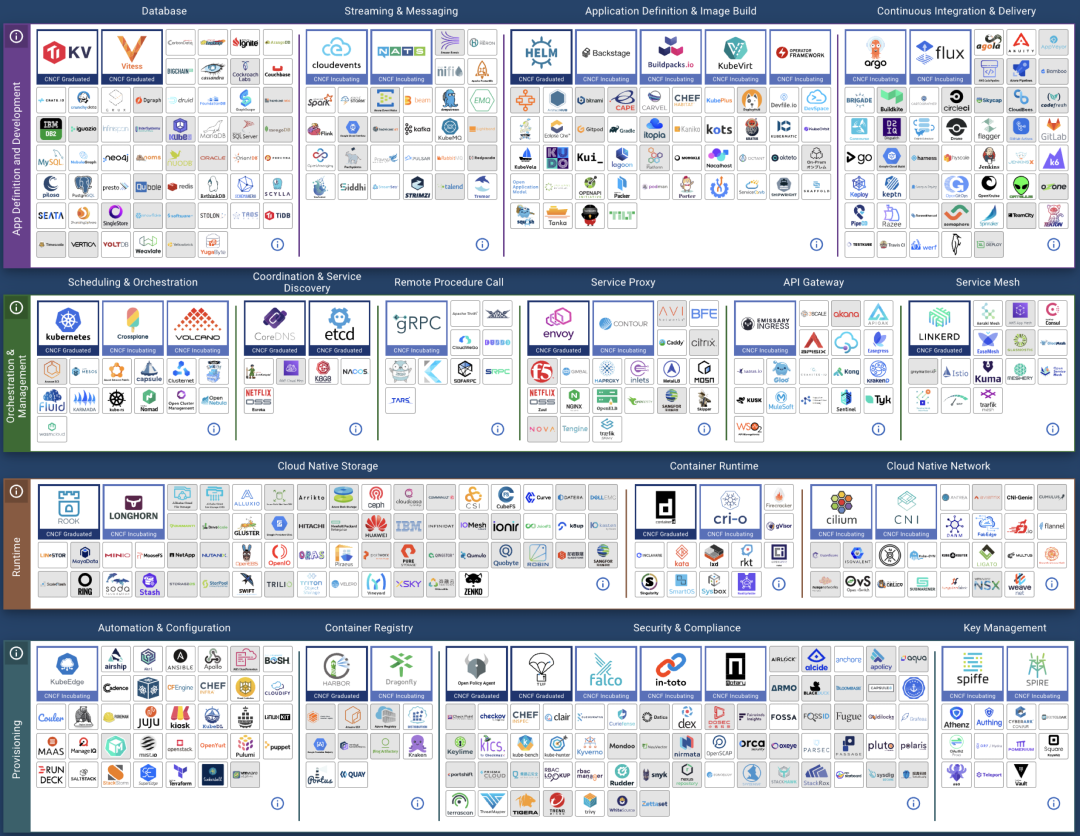

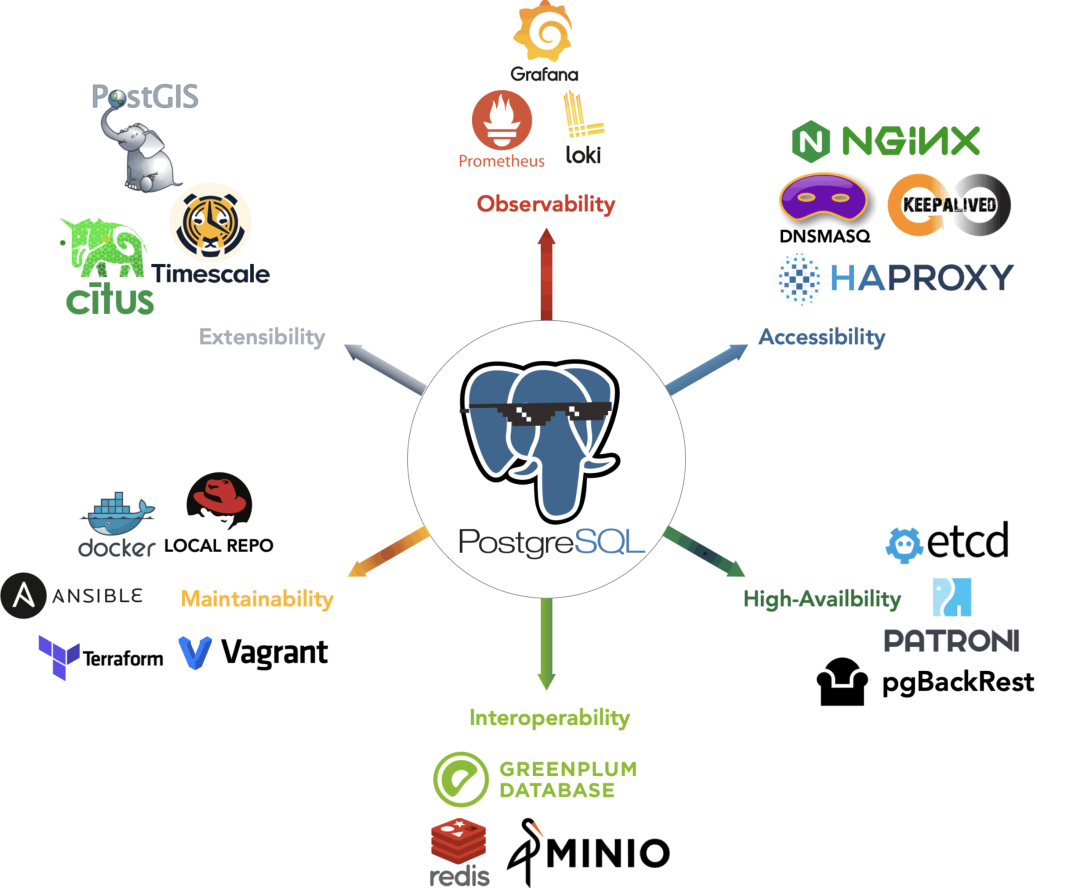

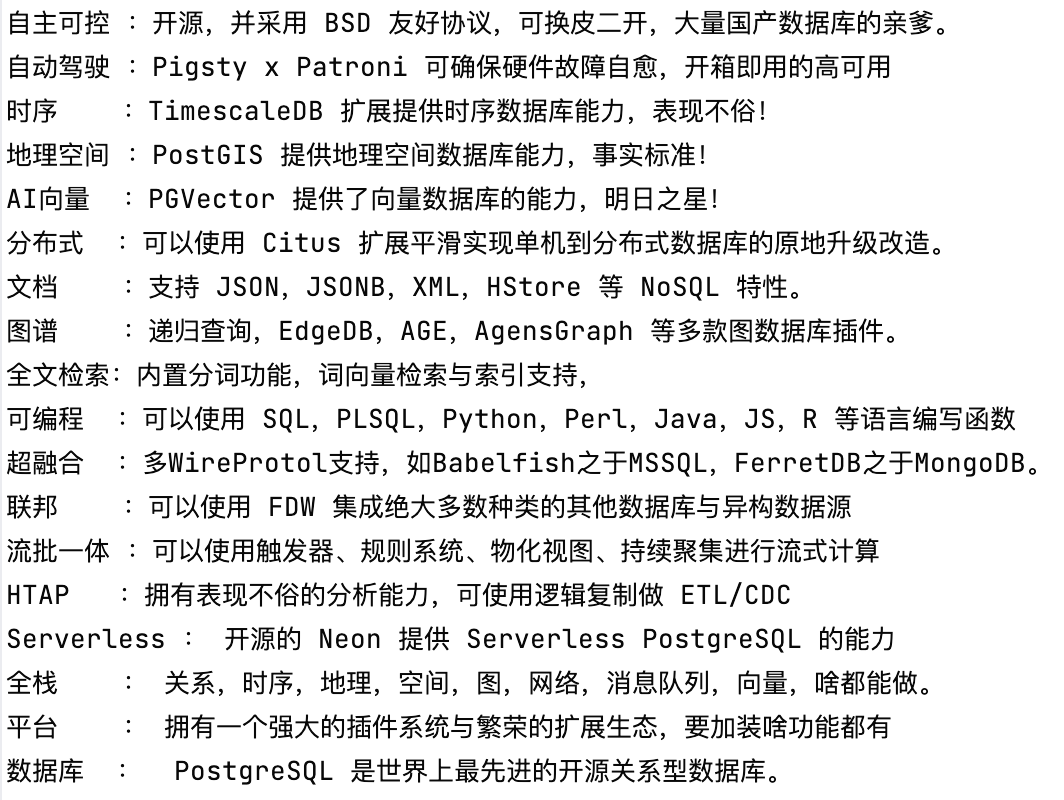

Abigale Kim from CMU has conducted research on scalability across mainstream databases, highlighting PostgreSQL’s superior extensibility among all DBMSs, boasting an unmatched number of extension plugins—375+ listed on PGXN alone, with actual ecosystem extensions surpassing a thousand.

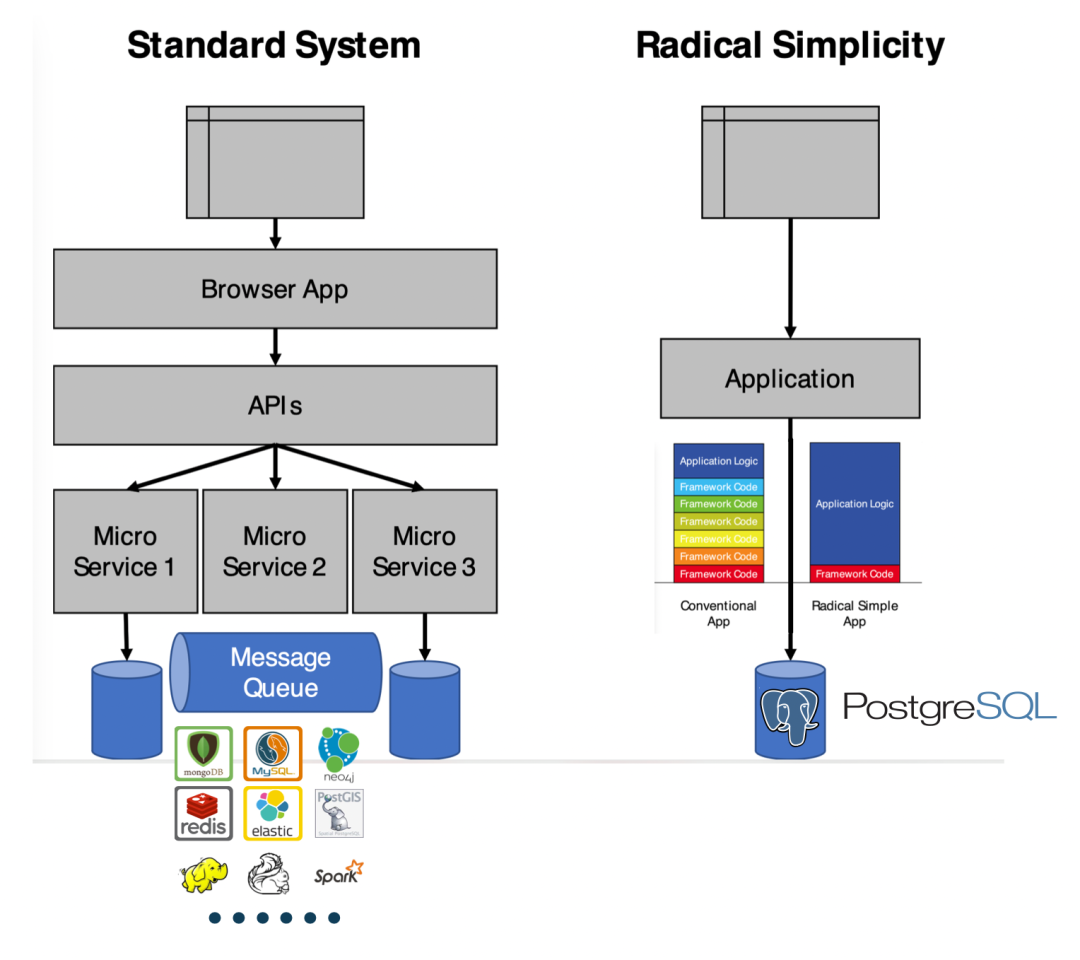

These plugins enable PostgreSQL to serve diverse functionalities—geospatial, time-series, vector search, machine learning, OLAP, full-text search, graph databases—effectively turning it into a multi-faceted, full-stack database. A single PostgreSQL instance can replace an array of specialized components: MySQL, MongoDB, Kafka, Redis, ElasticSearch, Neo4j, and even dedicated analytical data warehouses and data lakes.

While MySQL remains confined to its “relational OLTP database” niche, PostgreSQL has transcended its relational roots to become a multi-modal database and a platform for data management abstraction and development.

PostgreSQL is devouring the database world, internalizing the entire database realm through its plugin architecture. “Just use Postgres” has moved from being a fringe exploration by elite teams to a mainstream best practice.

In contrast, MySQL shows a lackluster enthusiasm for new functionalities—a major version update that should be rife with innovative ‘breaking changes’ turns out to be either lackluster features or insubstantial enterprise gimmicks.

Deteriorated Performance

The lack of features might not be an insurmountable issue—if a database excels at its core functionalities, architects can cobble together the required features using various data components.

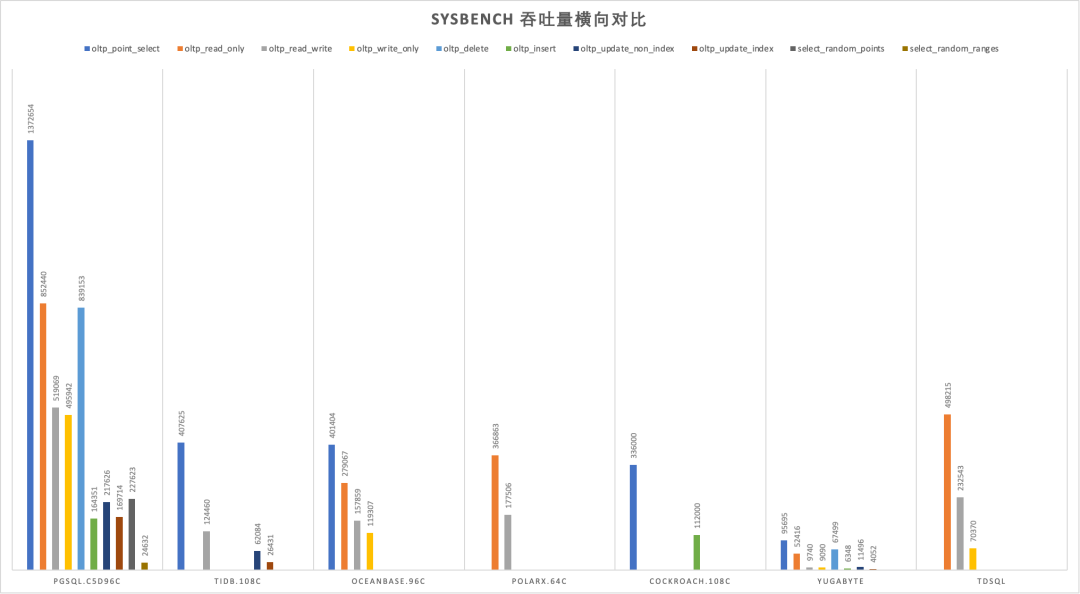

MySQL’s once-celebrated core attribute was its performance—notably in simple OLTP CRUD operations typical of internet-scale applications. Unfortunately, this strength is now under siege. Percona’s blog post “Sakila: Where Are You Going?” unveils a startling revelation:

Newer MySQL versions are performing worse than their predecessors.

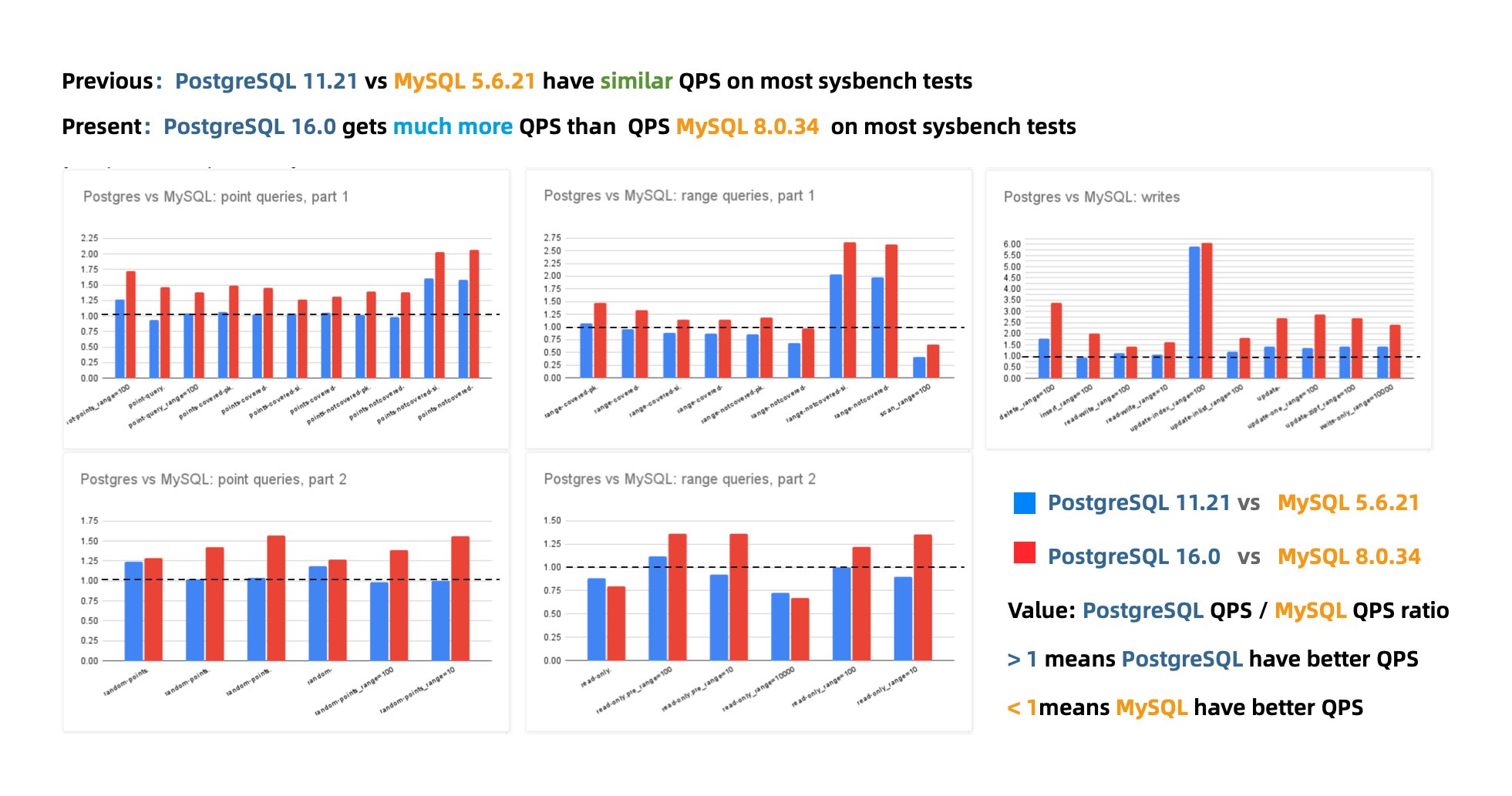

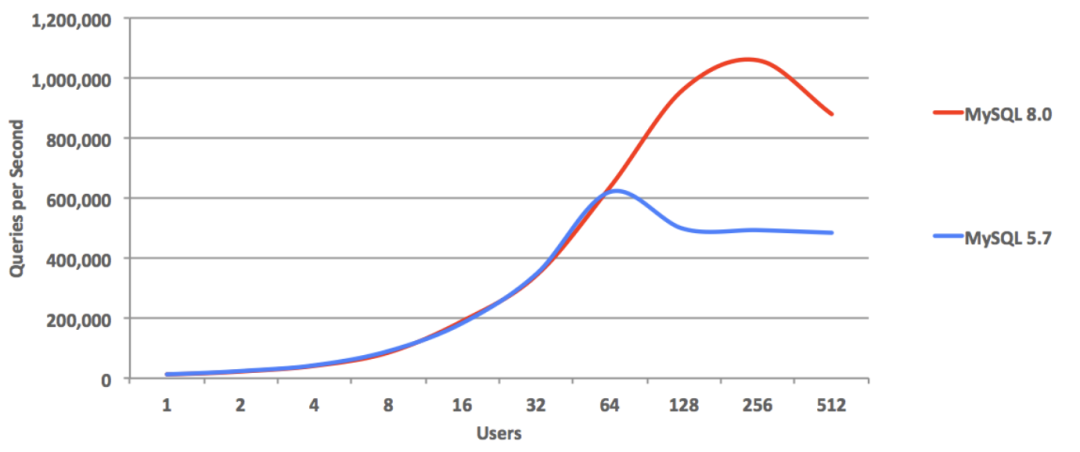

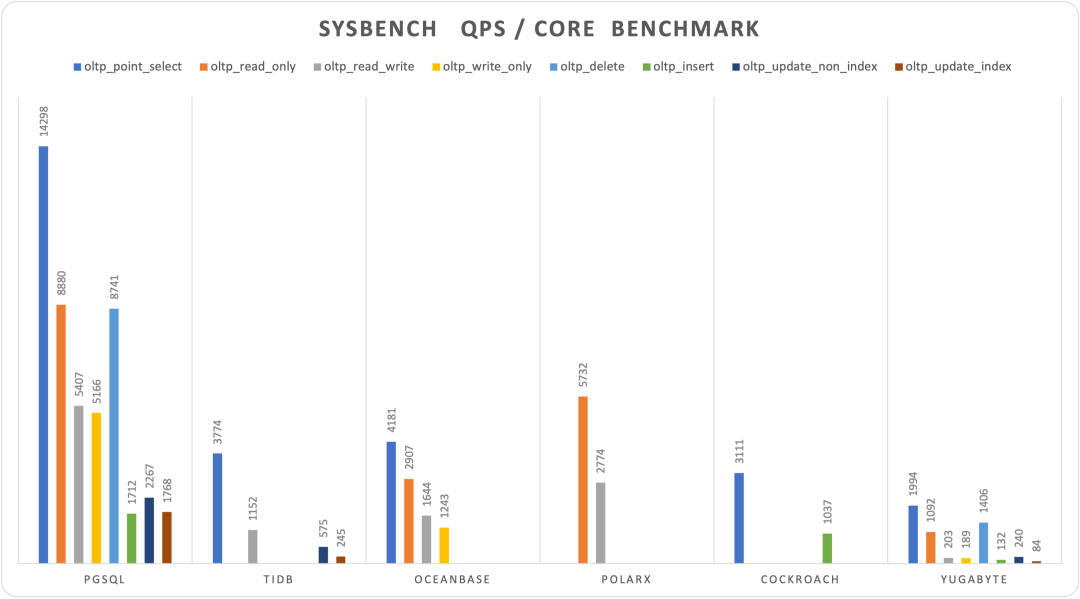

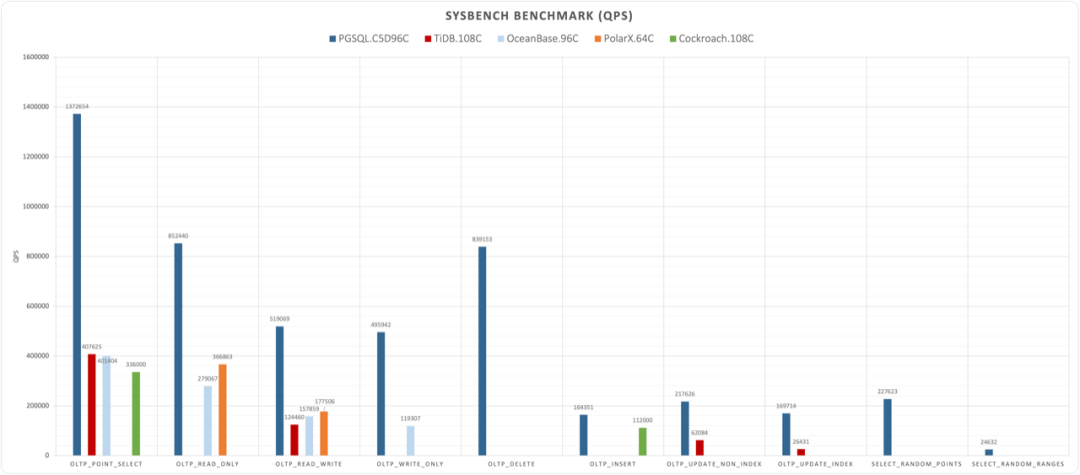

According to Percona’s benchmarks using sysbench and TPC-C, the latest MySQL 8.4 shows a performance degradation of up to 20% compared to MySQL 5.7. MySQL expert Mark Callaghan has further corroborated this trend in his detailed performance regression tests:

MySQL 8.0.36 shows a 25% – 40% drop in QPS throughput performance compared to MySQL 5.6!

While there have been some optimizer improvements in MySQL 8.x, enhancing performance in complex query scenarios, complex queries were never MySQL’s forte. Conversely, a significant drop in the fundamental OLTP CRUD performance is indefensible.

Peter Zaitsev commented in his post “Oracle Has Finally Killed MySQL”: “Compared to MySQL 5.6, MySQL 8.x has shown a significant performance decline in single-threaded simple workloads. One might argue that adding features inevitably impacts performance, but MariaDB shows much less performance degradation, and PostgreSQL has managed to significantly enhance performance while adding features.”

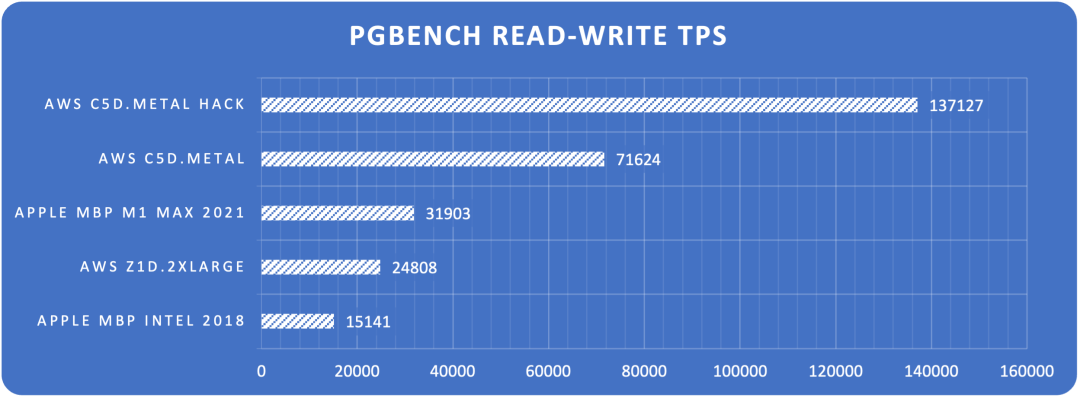

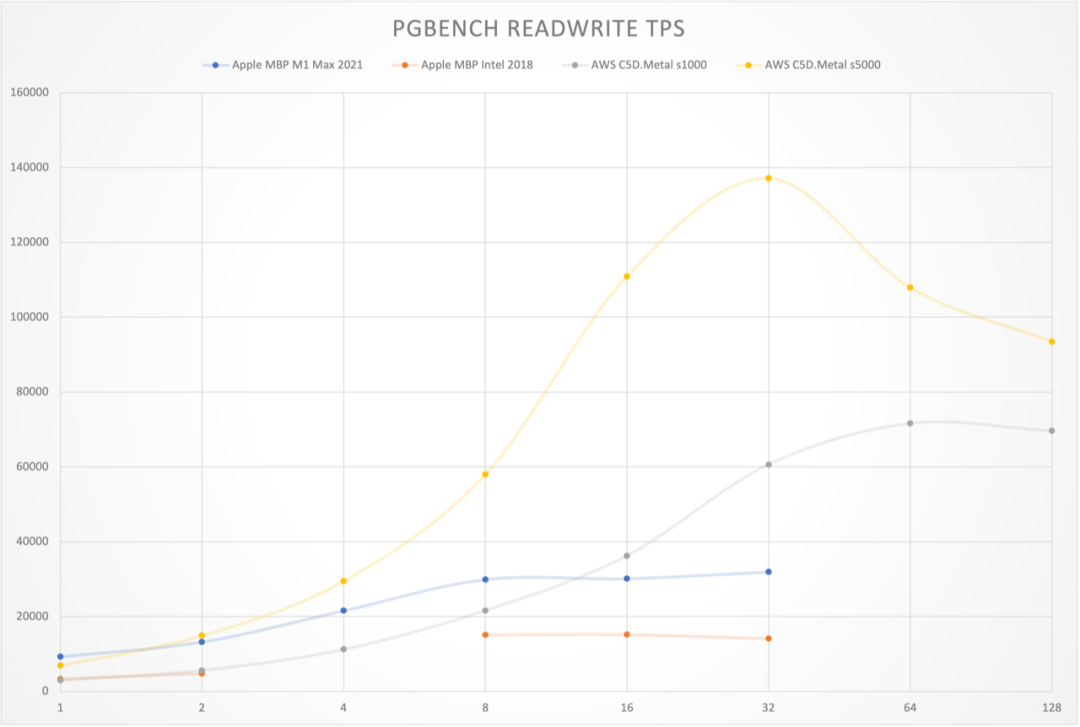

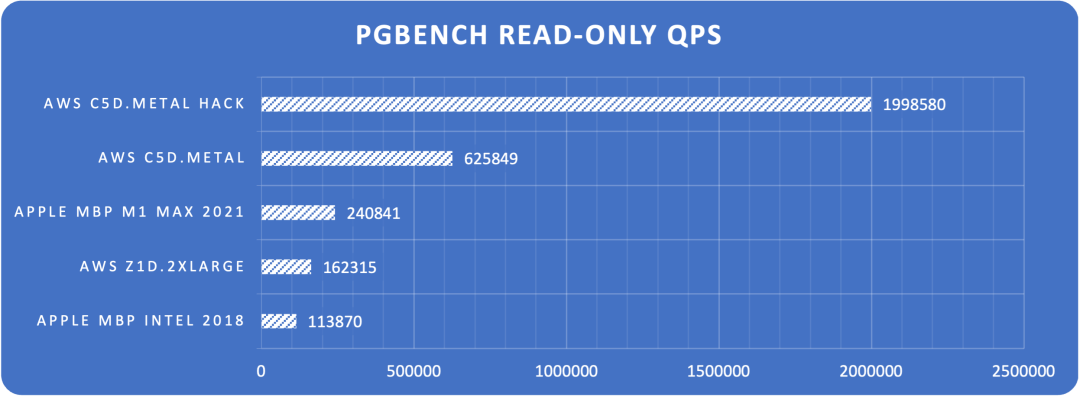

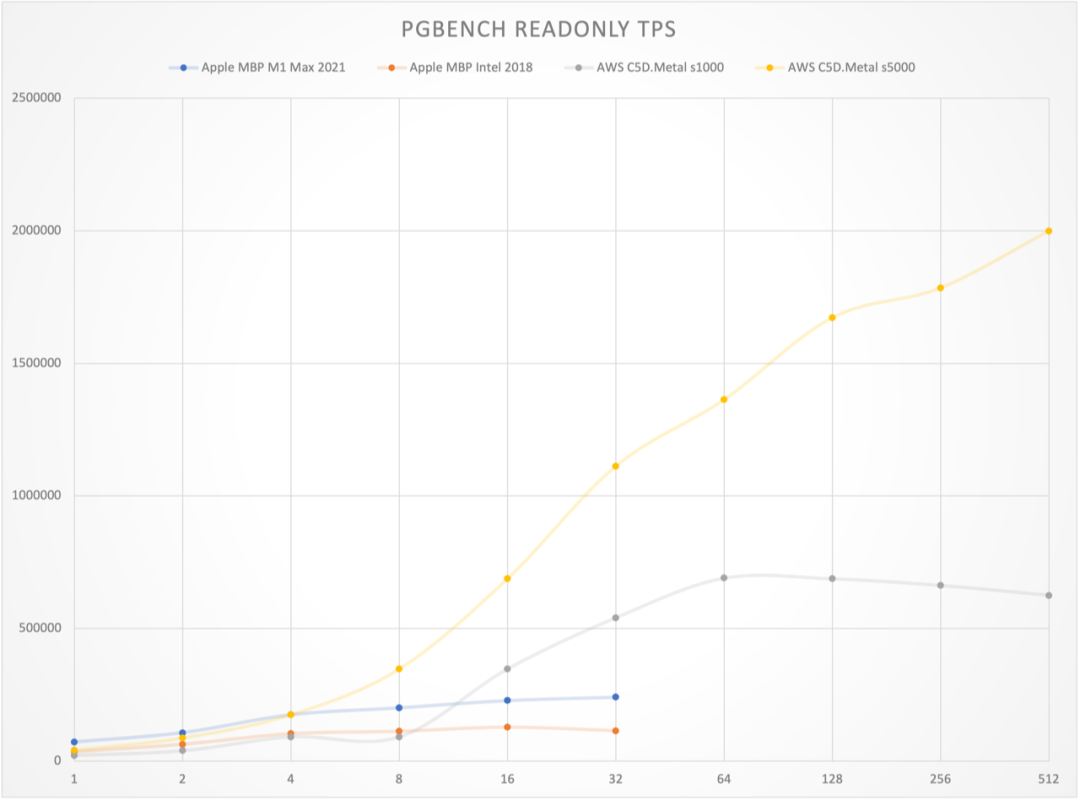

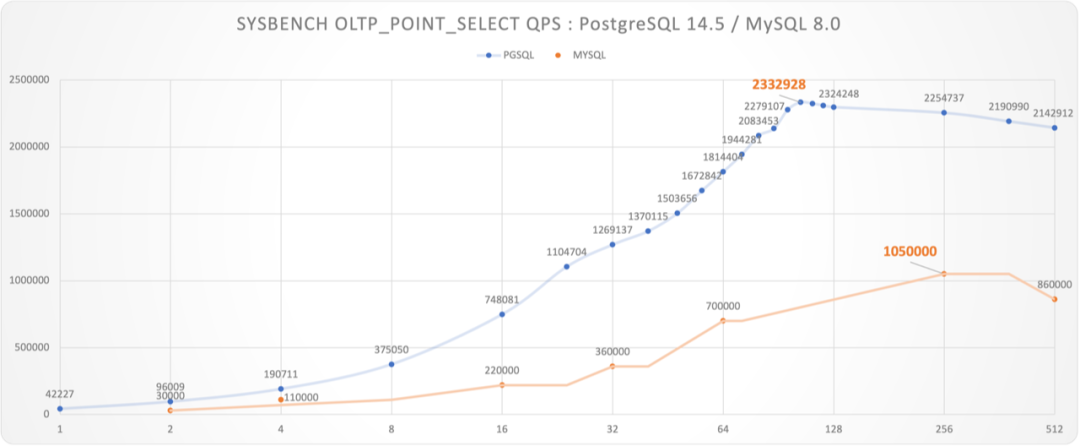

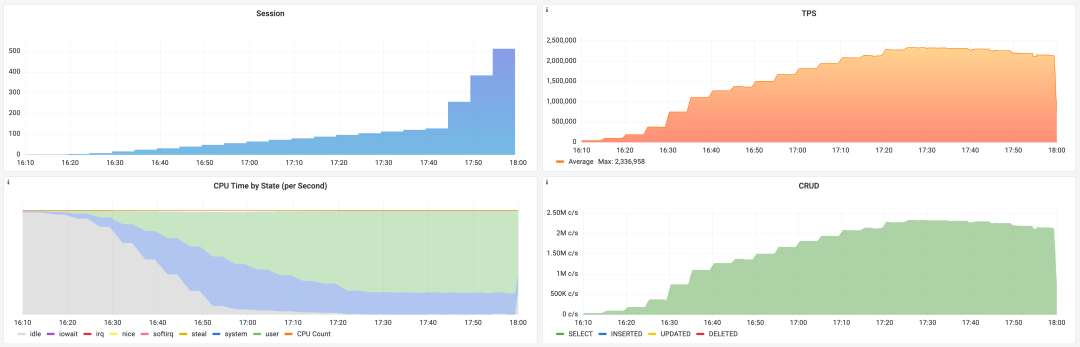

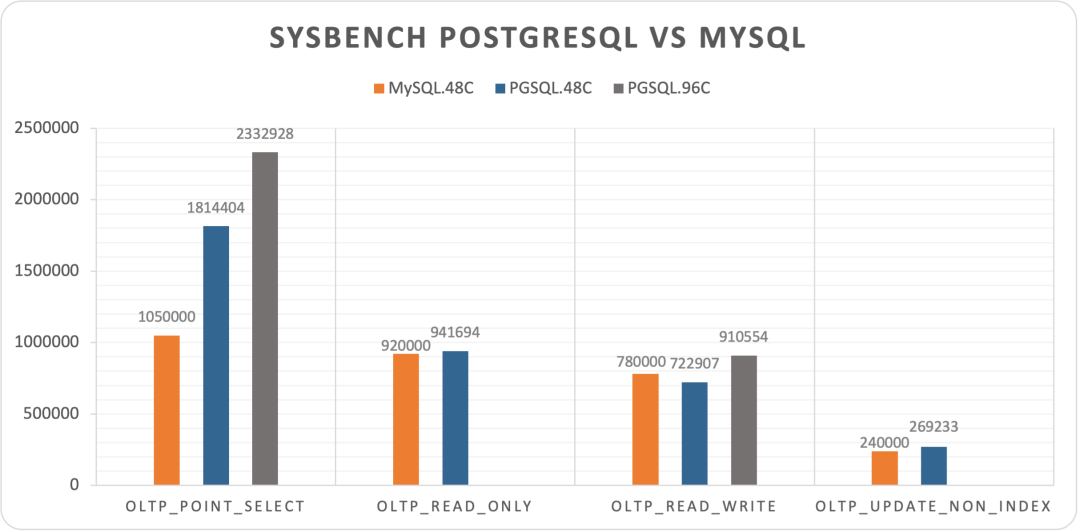

Years ago, the industry consensus was that PostgreSQL and MySQL performed comparably in simple OLTP CRUD scenarios. However, as PostgreSQL has continued to improve, it has vastly outpaced MySQL in performance. PostgreSQL now significantly exceeds MySQL in various read and write scenarios, with throughput improvements ranging from 200% to even 500% in some cases.

The performance edge that MySQL once prided itself on no longer exists.

The Incurable Isolation Levels

While performance issues can usually be patched up, correctness issues are a different beast altogether.

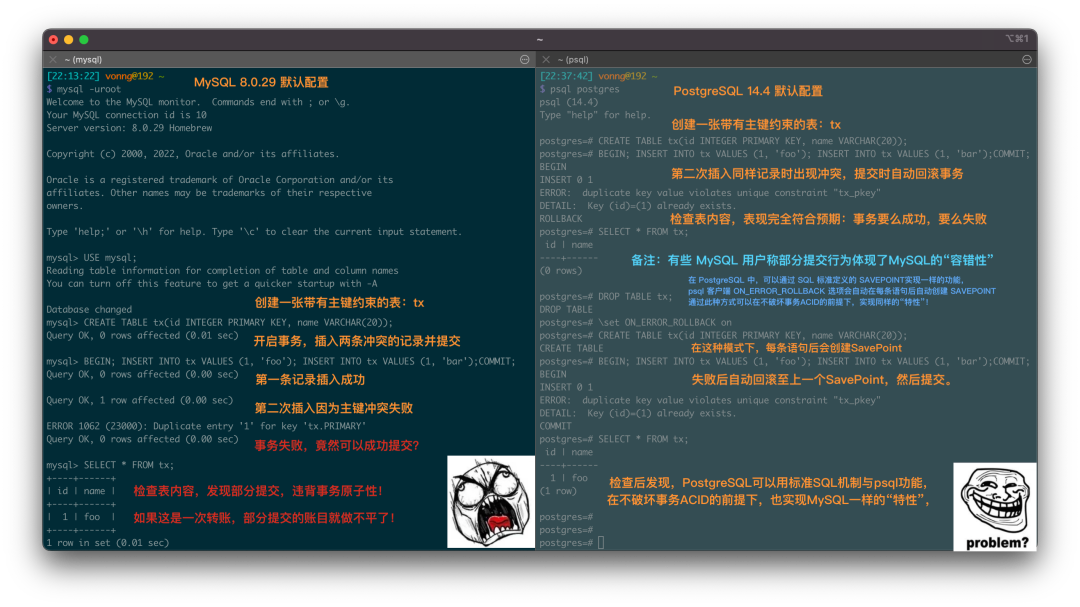

An article, “The Grave Correctness Problems with MySQL?”, points out that MySQL falls embarrassingly short on correctness—a fundamental attribute expected of any respectable database product.

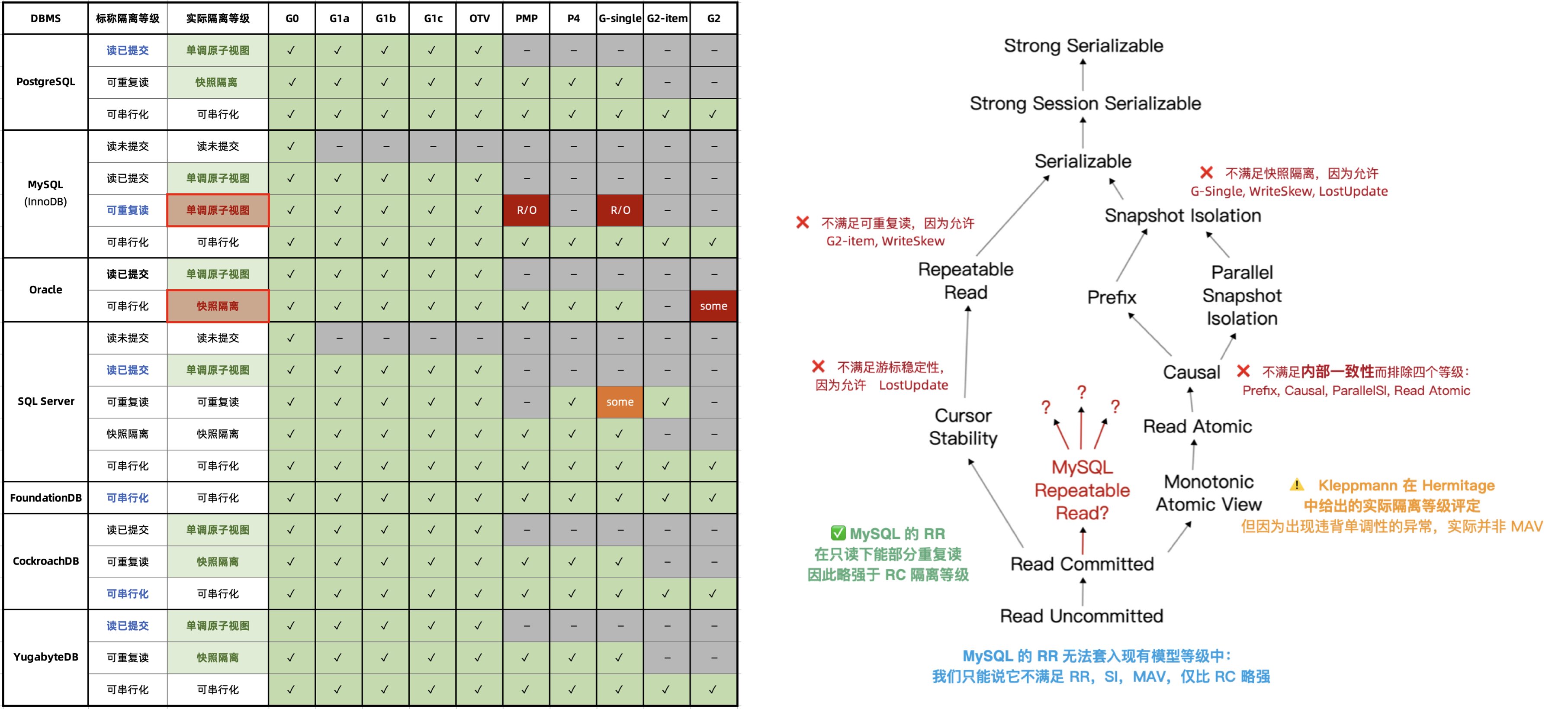

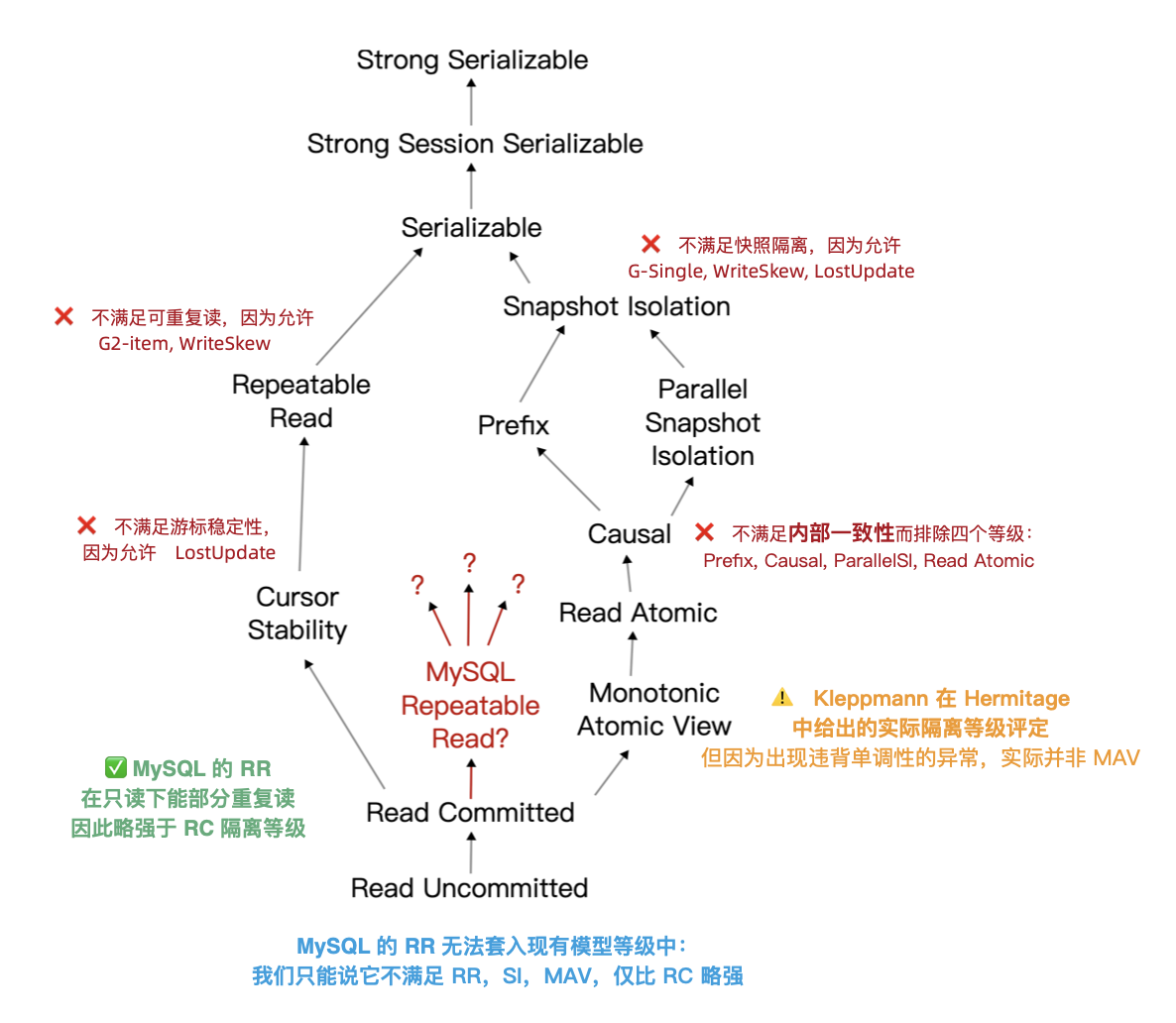

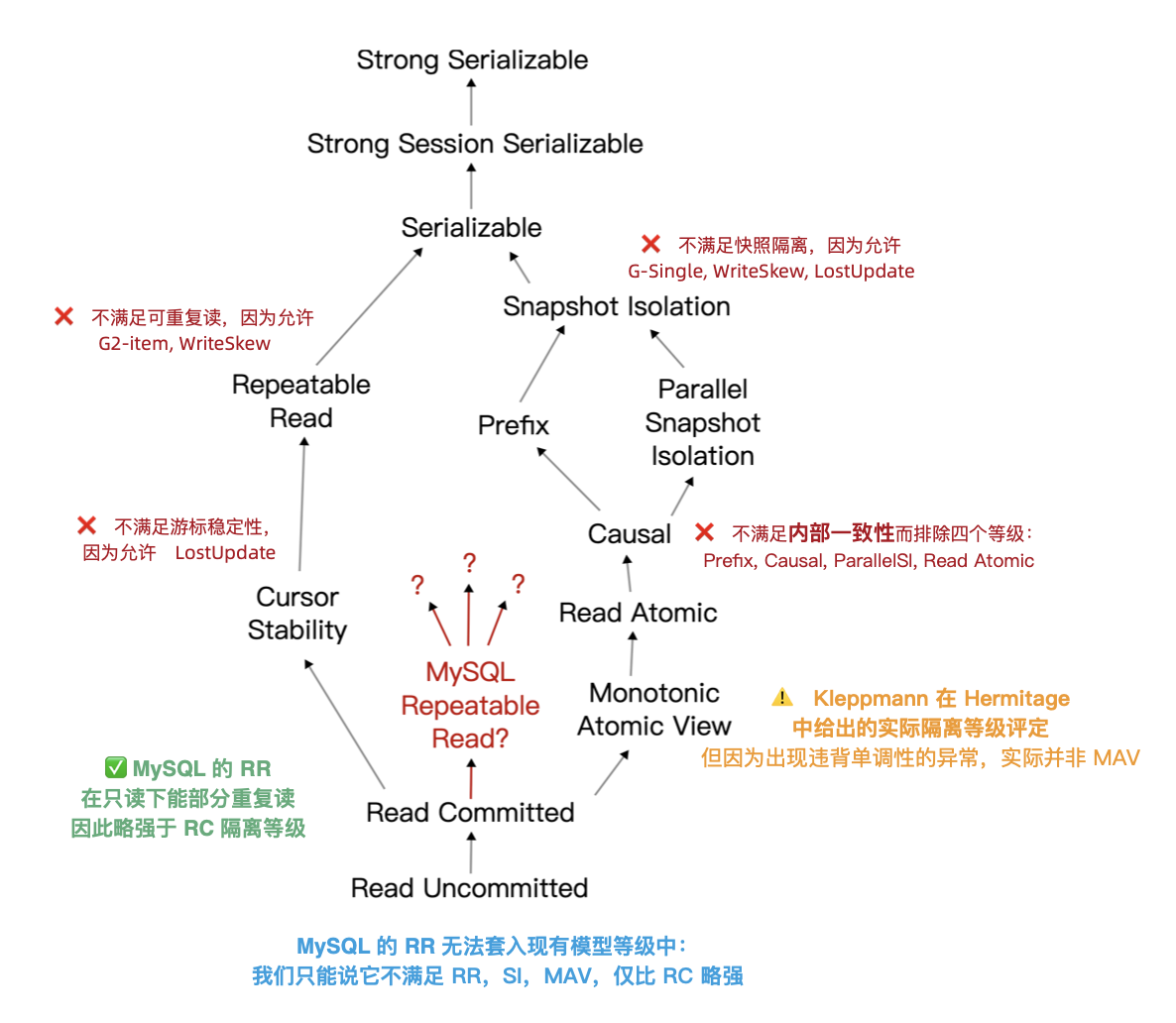

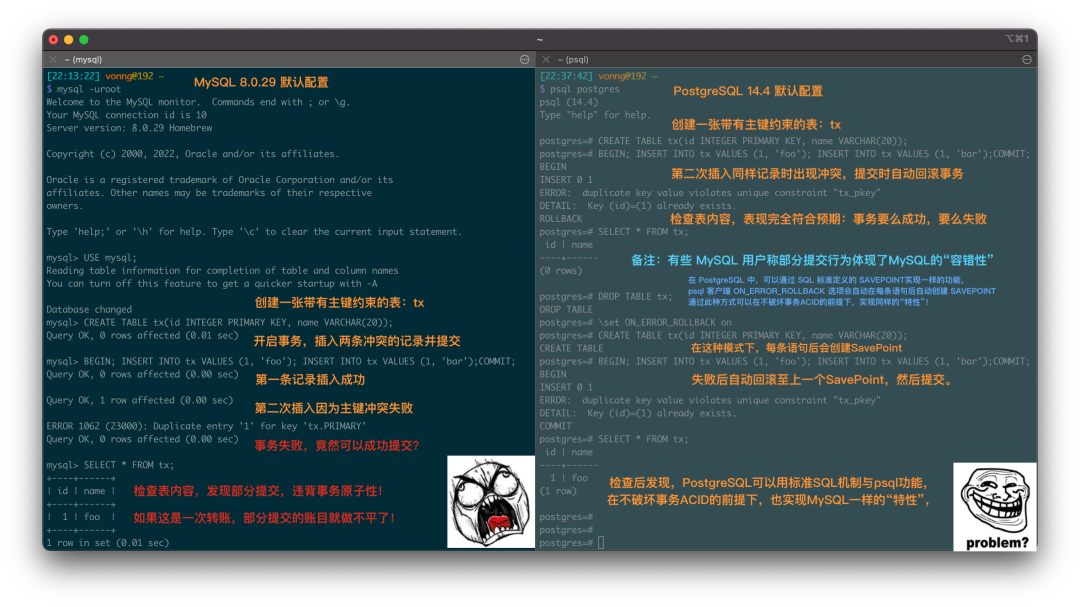

The renowned distributed transaction testing organization, JEPSEN, discovered that the Repeatable Read (RR) isolation level claimed by MySQL’s documentation actually provides much weaker correctness guarantees. MySQL 8.0.34’s default RR isolation level isn’t truly repeatable read, nor is it atomic or monotonic, failing even the basic threshold of Monotonic Atomic View (MAV).

MySQL’s ACID properties are flawed and do not align with their documentation—a blind trust in these false promises can lead to severe correctness issues, such as data discrepancies and reconciliation errors, which are intolerable in scenarios where data integrity is crucial, like finance.

Moreover, the Serializable (SR) isolation level in MySQL, which could “avoid” these anomalies, is hard to use in production and isn’t recognized as best practice by official documentation or the community. While expert developers might circumvent such issues by explicitly locking in queries, this approach severely impacts performance and is prone to deadlocks.

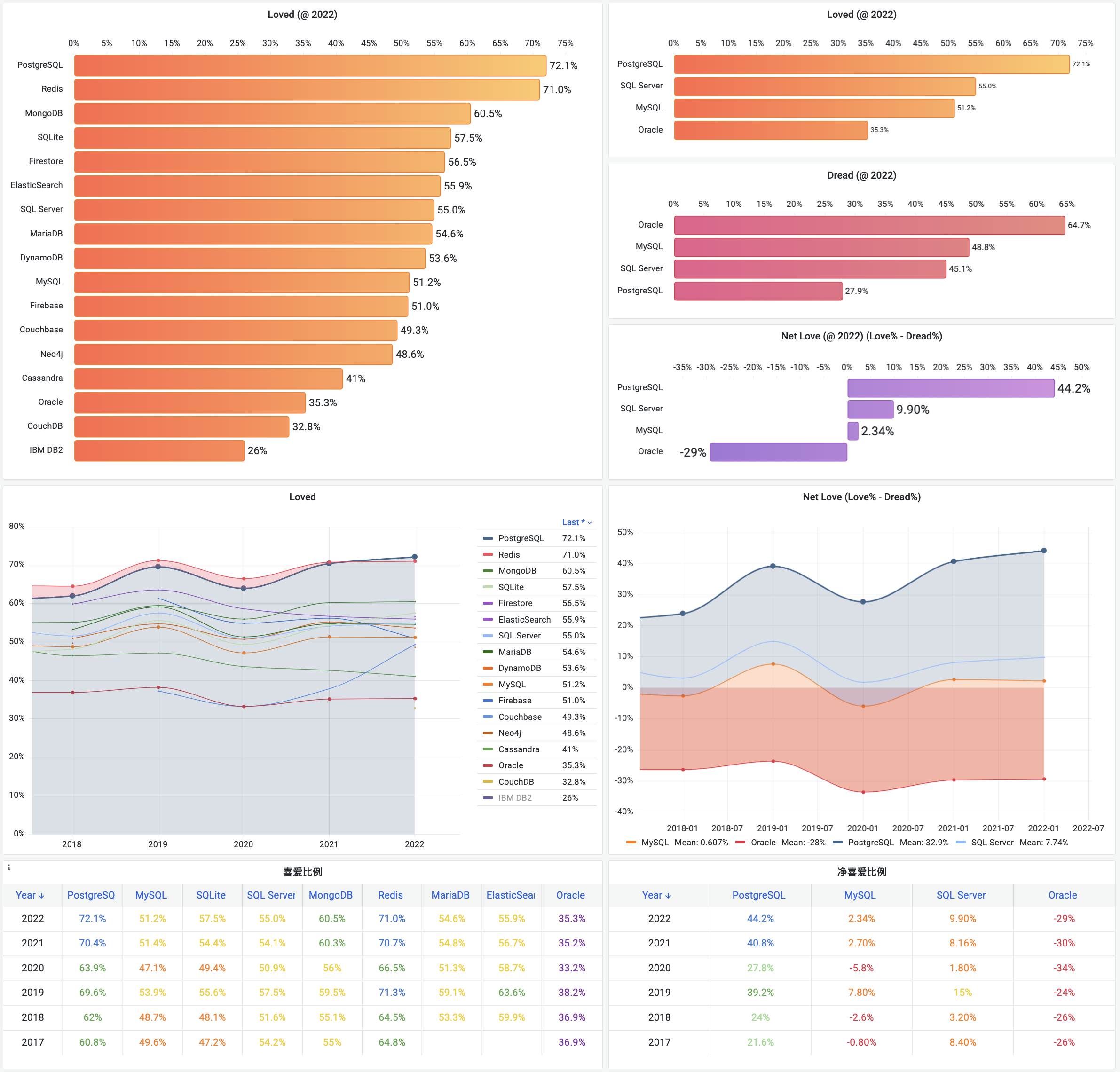

In contrast, PostgreSQL’s introduction of Serializable Snapshot Isolation (SSI) in version 9.1 offers a complete serializable isolation level with minimal performance overhead—achieving a level of correctness even Oracle struggles to match.

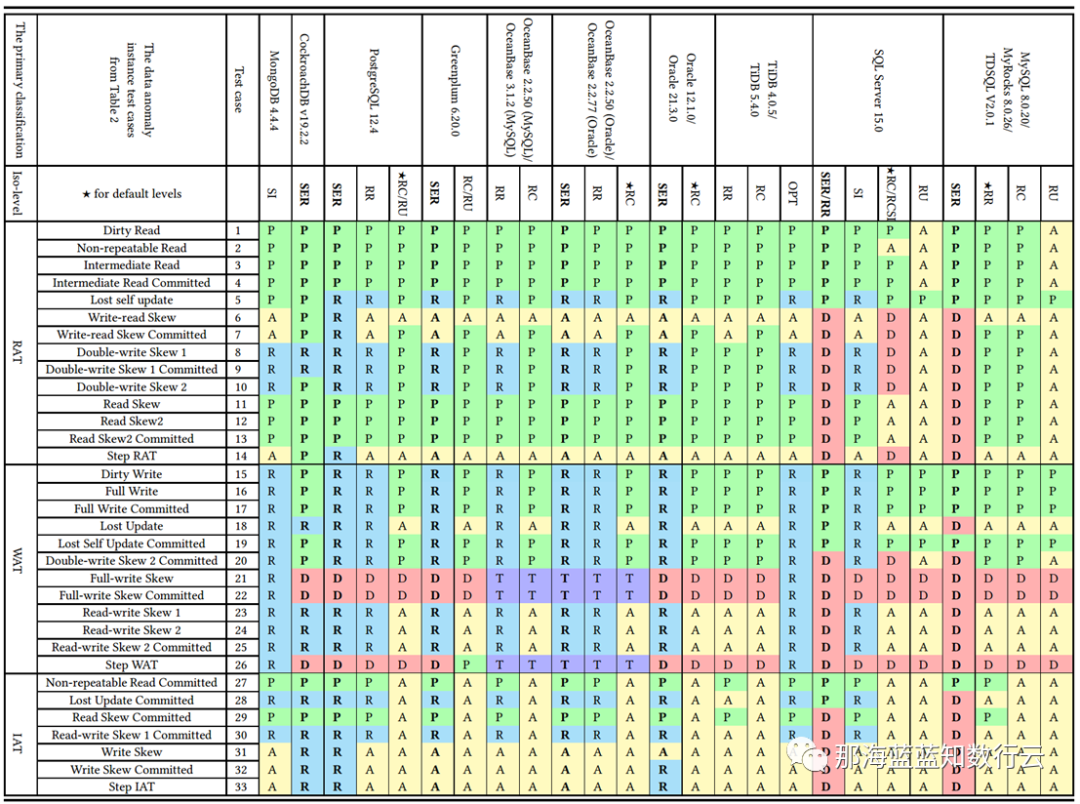

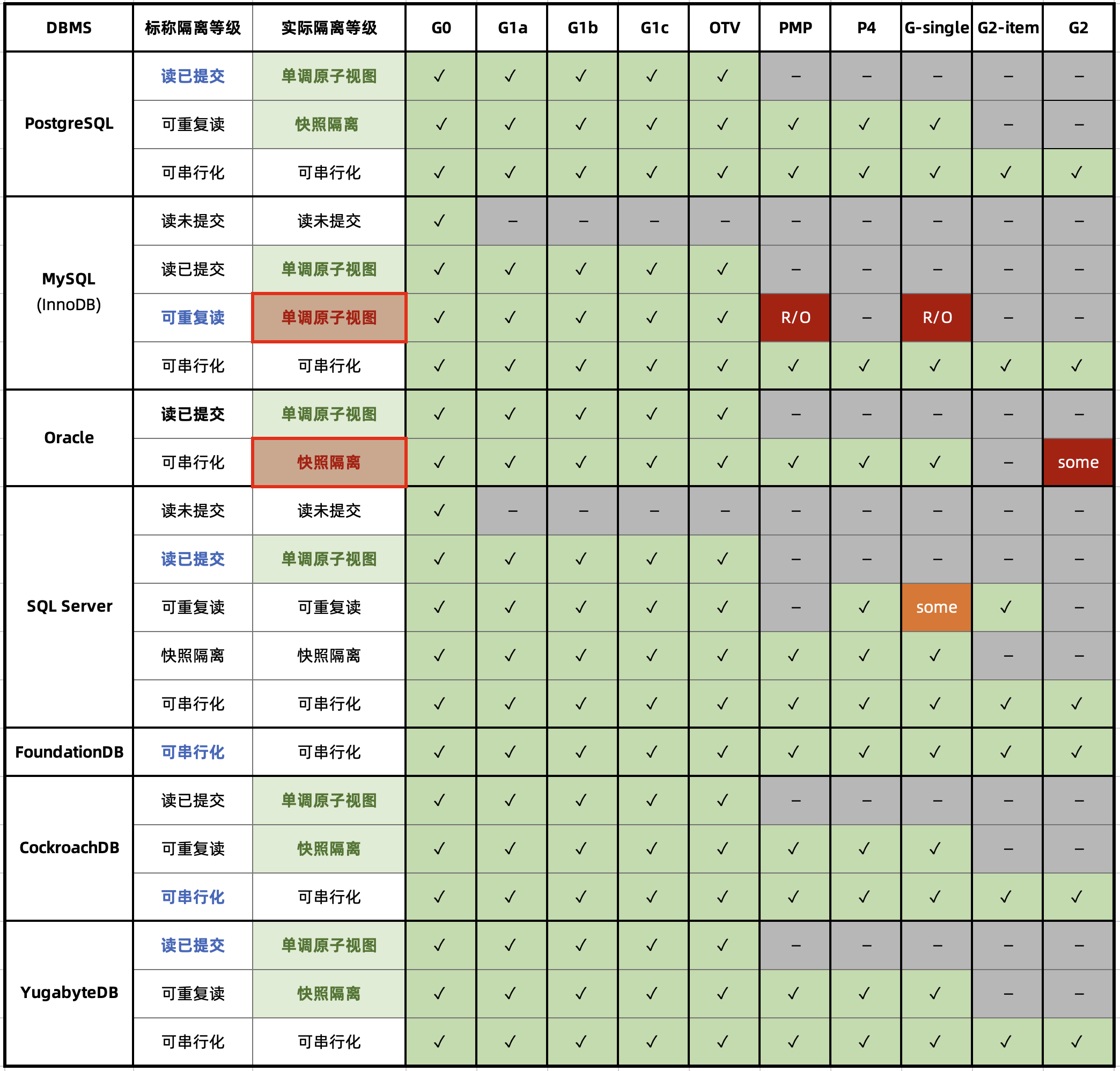

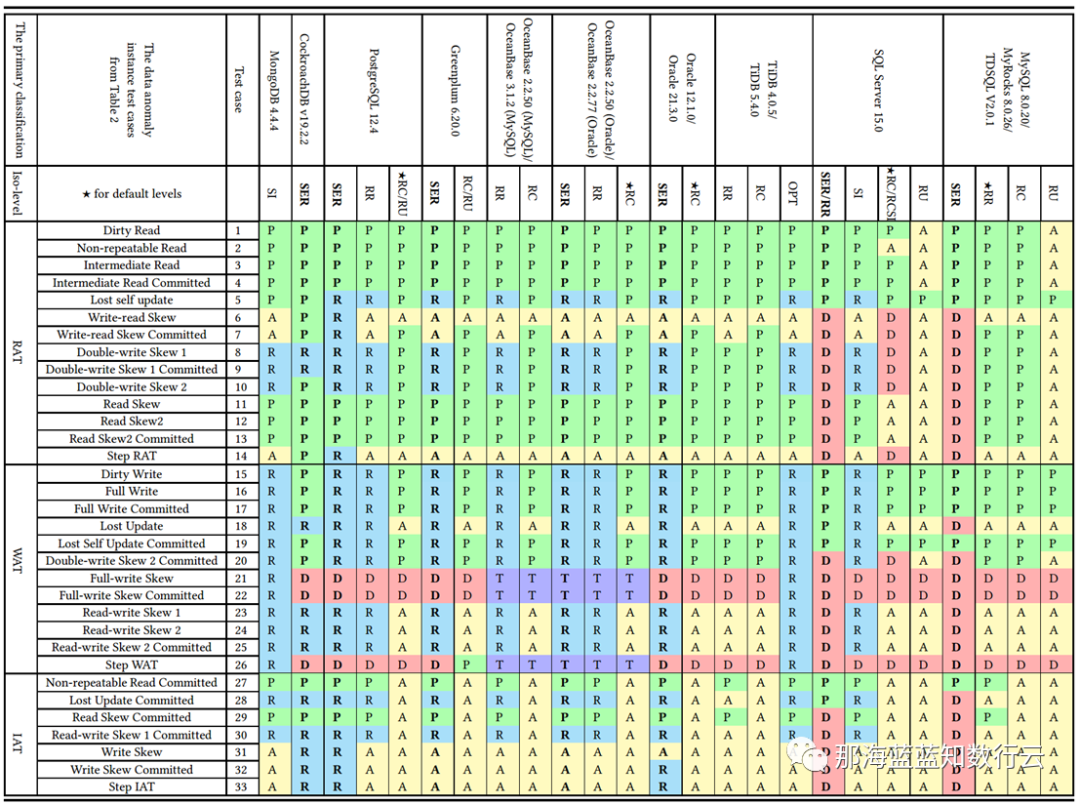

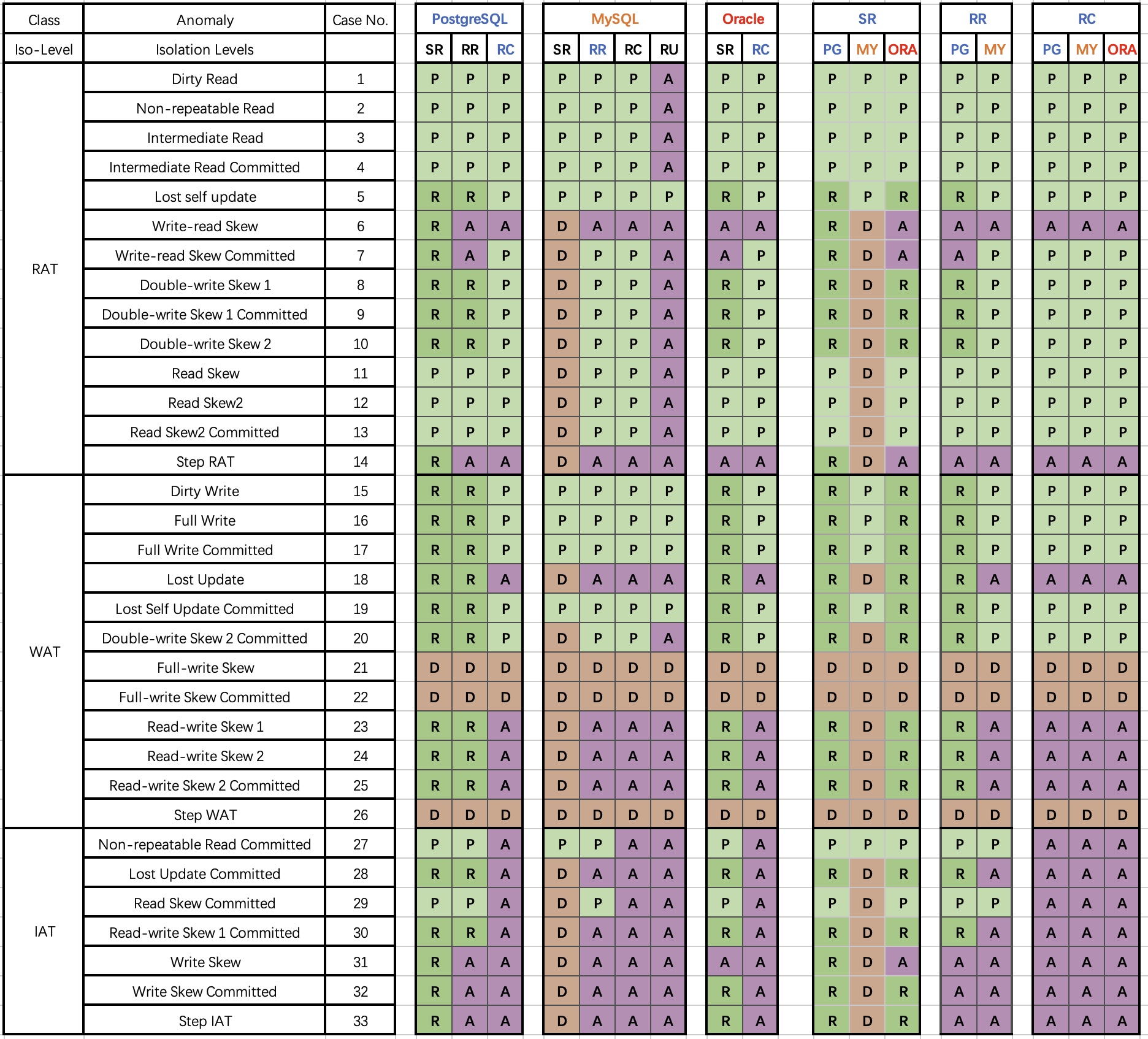

Professor Li Haixiang’s paper, “The Consistency Pantheon”, systematically evaluates the correctness of isolation levels across mainstream DBMSs. The chart uses blue/green to indicate correct handling rules/rollbacks to avoid anomalies; yellow A indicates anomalies, with more implying greater correctness issues; red “D” indicates performance-impacting deadlock detection used to handle anomalies, with more Ds indicating severe performance issues.

It’s clear that the best correctness implementation (no yellow A) is PostgreSQL’s SR, along with CockroachDB’s SR based on PG, followed by Oracle’s slightly flawed SR; mainly, these systems avoid concurrency anomalies through mechanisms and rules. Meanwhile, MySQL shows a broad swath of yellow As and red Ds, with a level of correctness and implementation that is crudely inadequate.

Doing things right is critical, and correctness should not be a trade-off. Early on, the open-source relational database giants MySQL and PostgreSQL chose divergent paths: MySQL sacrificed correctness for performance, while the academically inclined PostgreSQL opted for correctness at the expense of performance.

During the early days of the internet boom, MySQL surged ahead due to its performance advantages. However, as performance becomes less of a core concern, correctness has emerged as MySQL’s fatal flaw. What’s more tragic is that even the performance MySQL sacrificed correctness for is no longer competitive, a fact that’s disheartening.

The Shrinking Ecosystem Scale

For any technology, the scale of its user base directly determines the vibrancy of its ecosystem. Even a dying camel is larger than a horse, and a rotting ship still holds three pounds of nails. MySQL once soared with the winds of the internet, amassing a substantial legacy, aptly captured by its slogan—“The world’s most popular open-source relational database”.

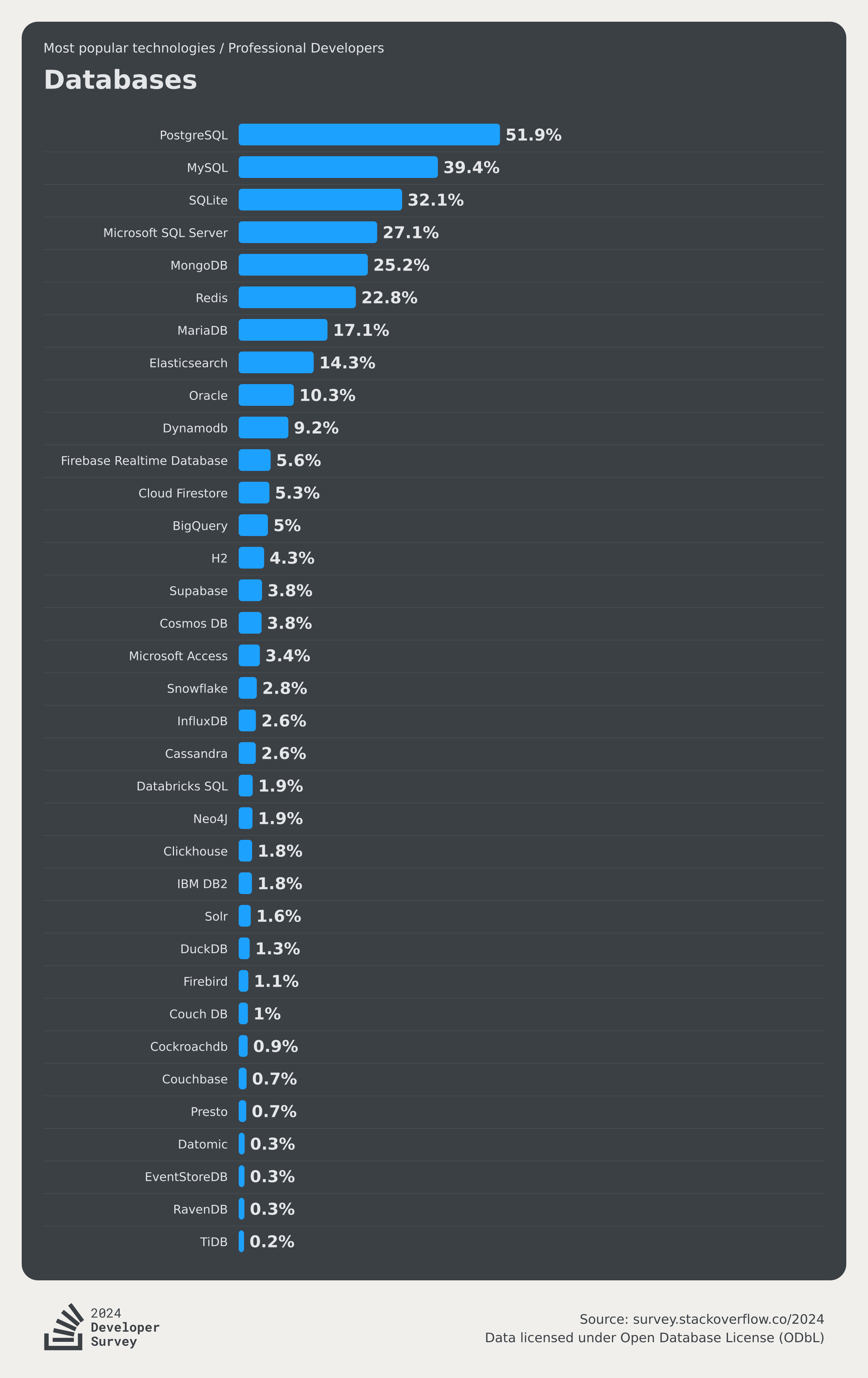

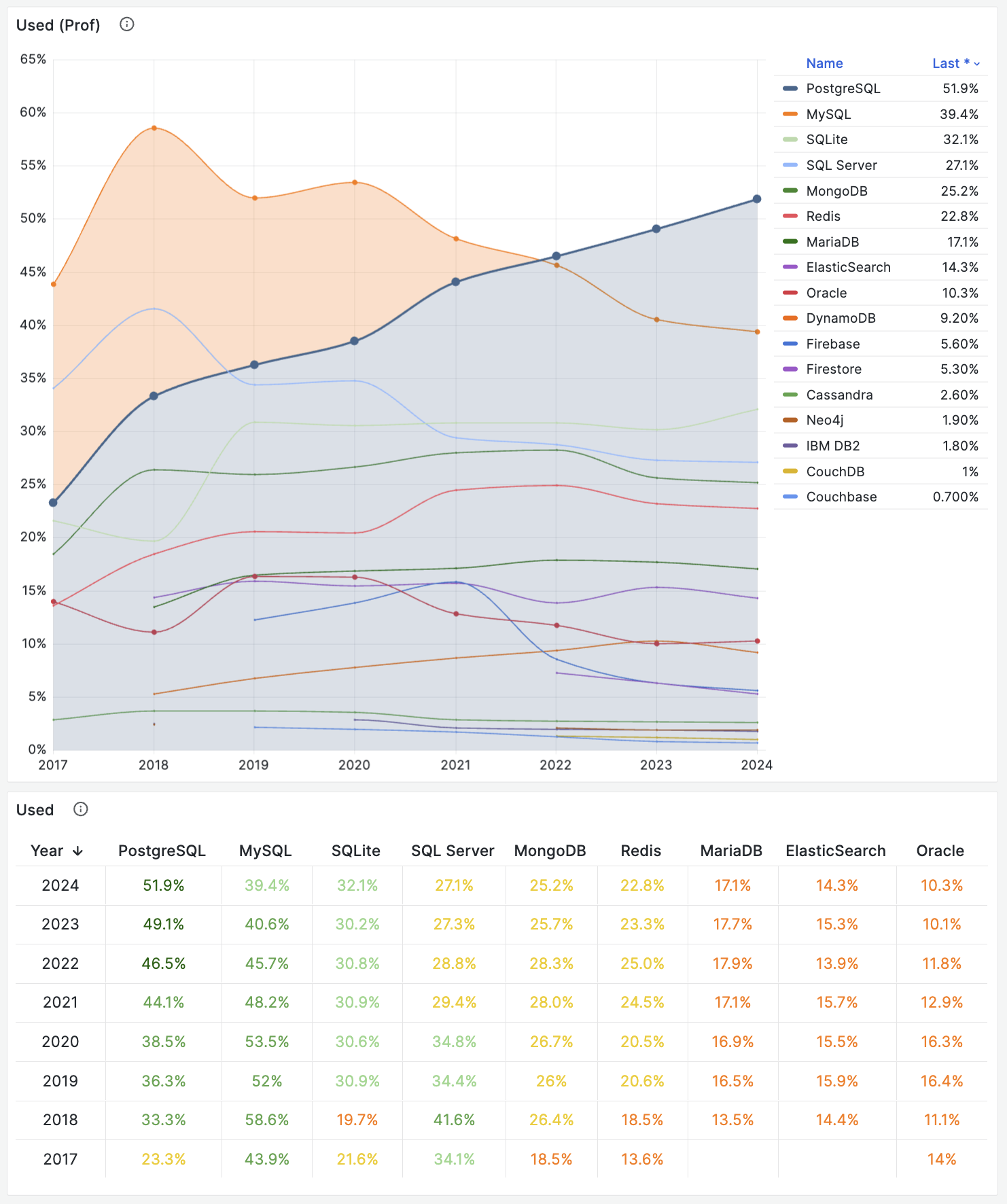

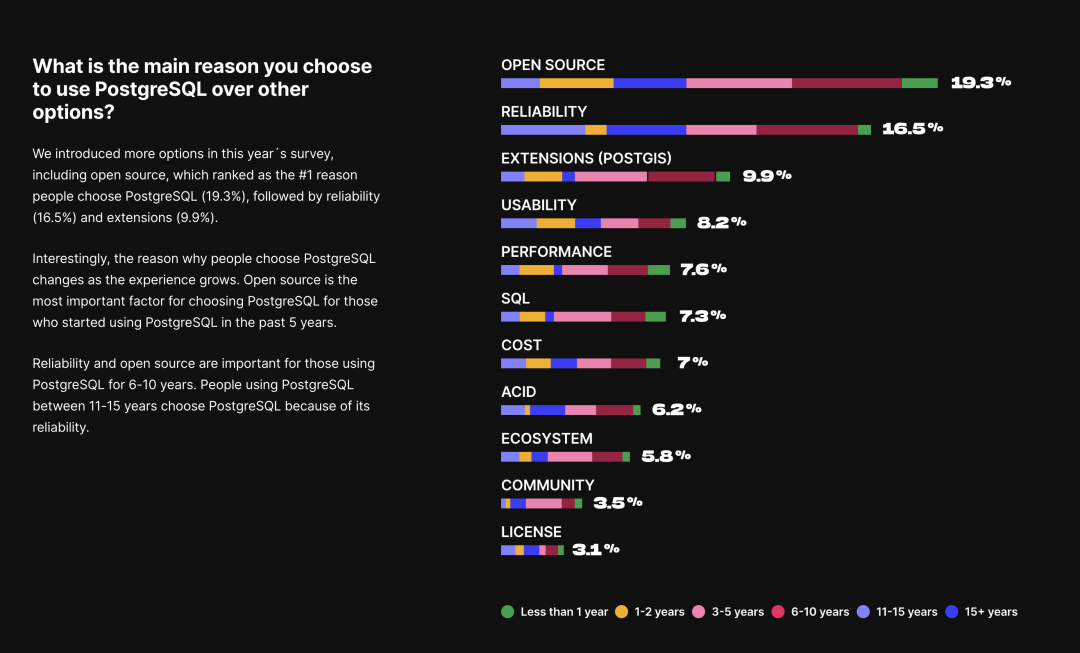

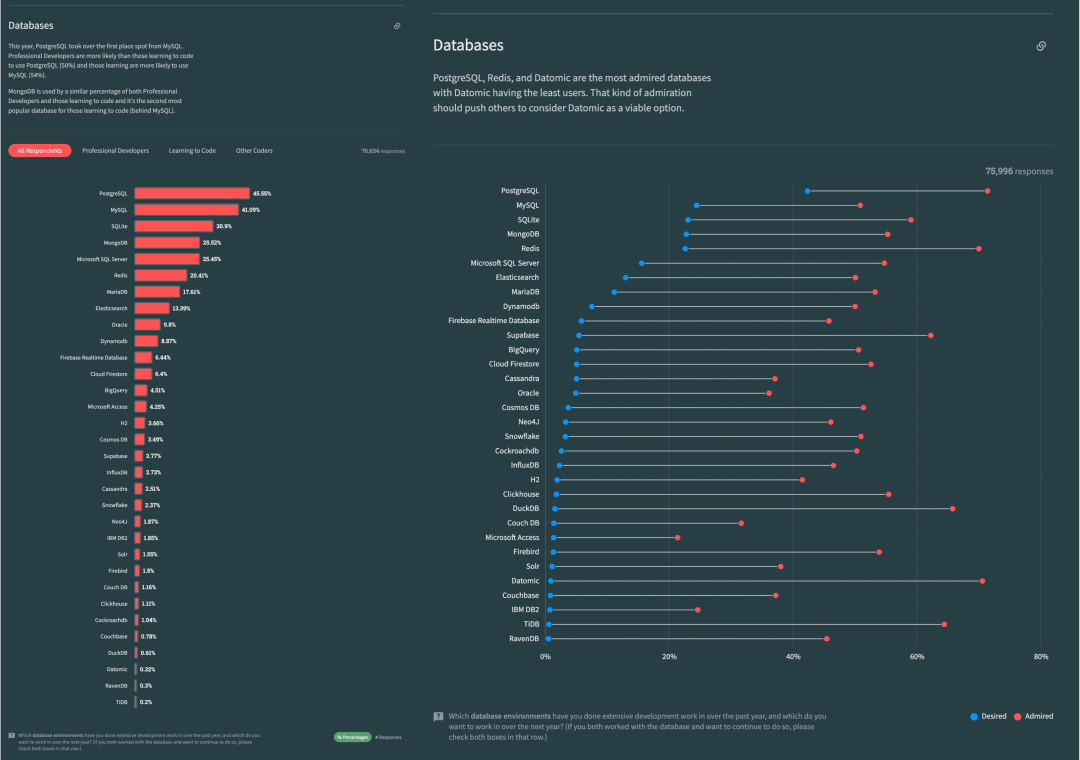

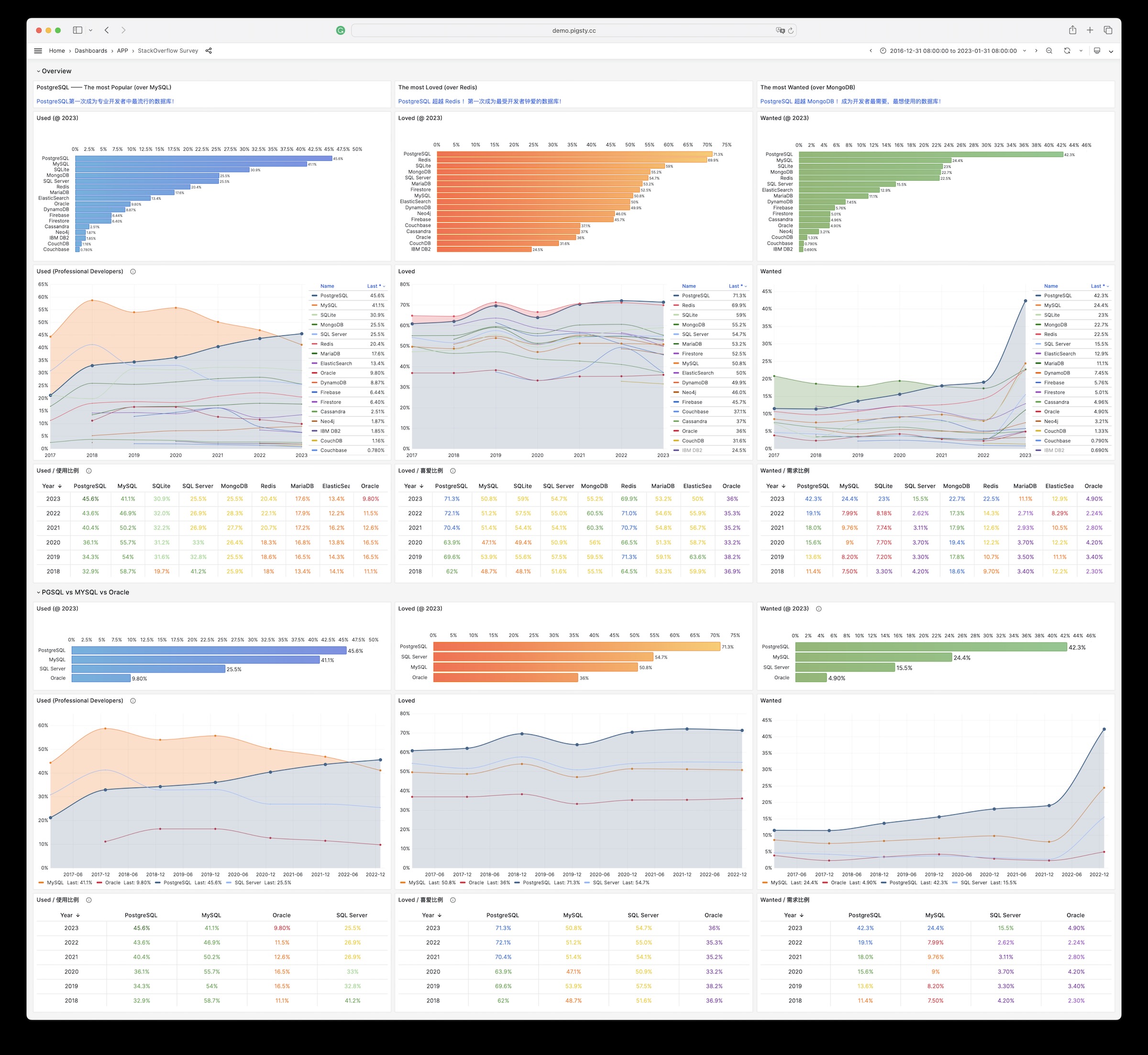

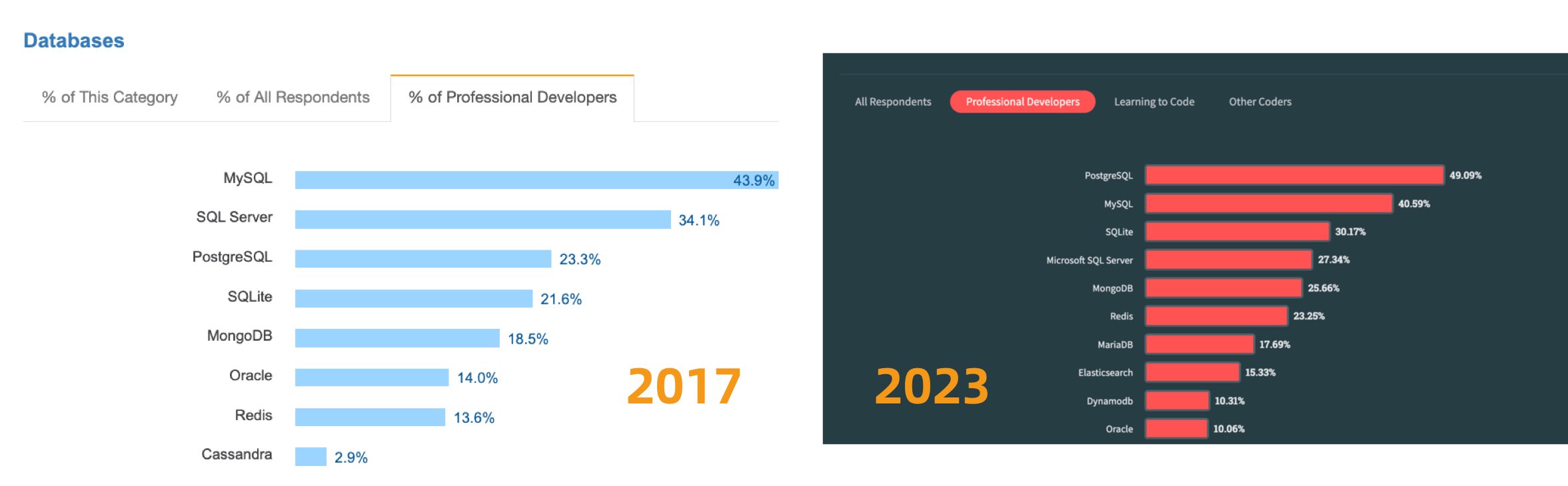

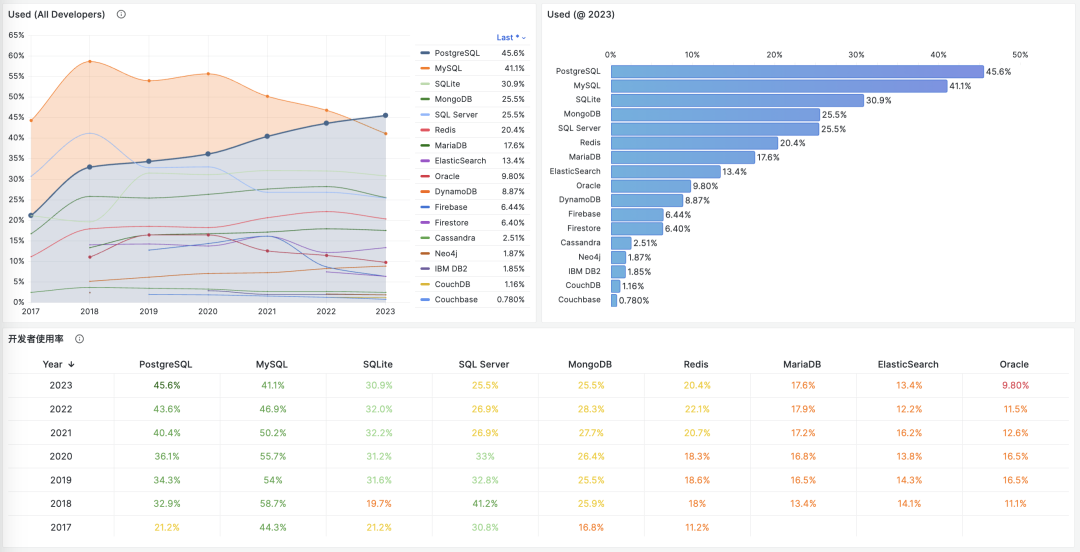

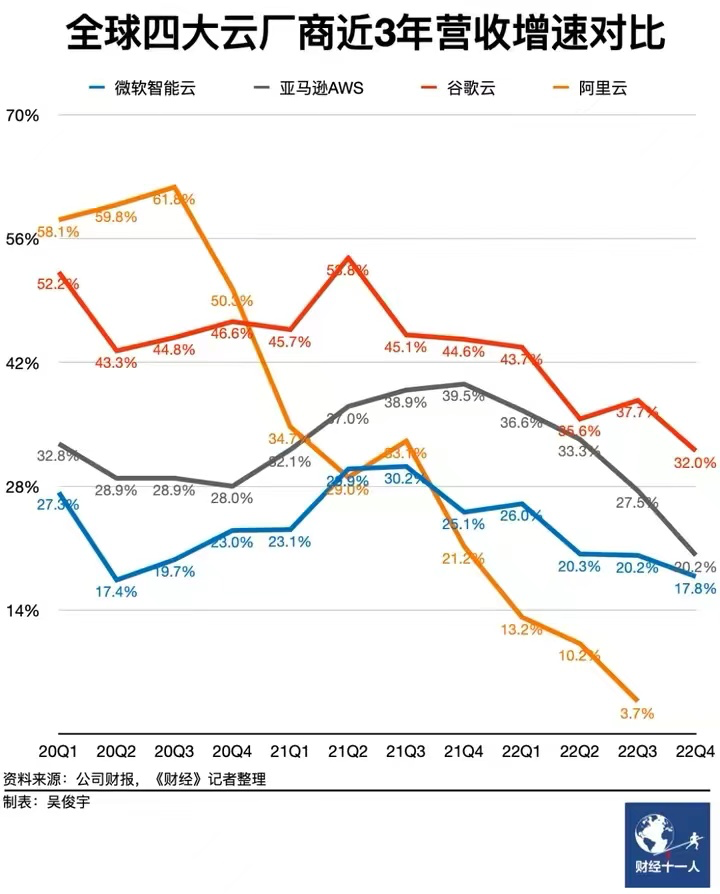

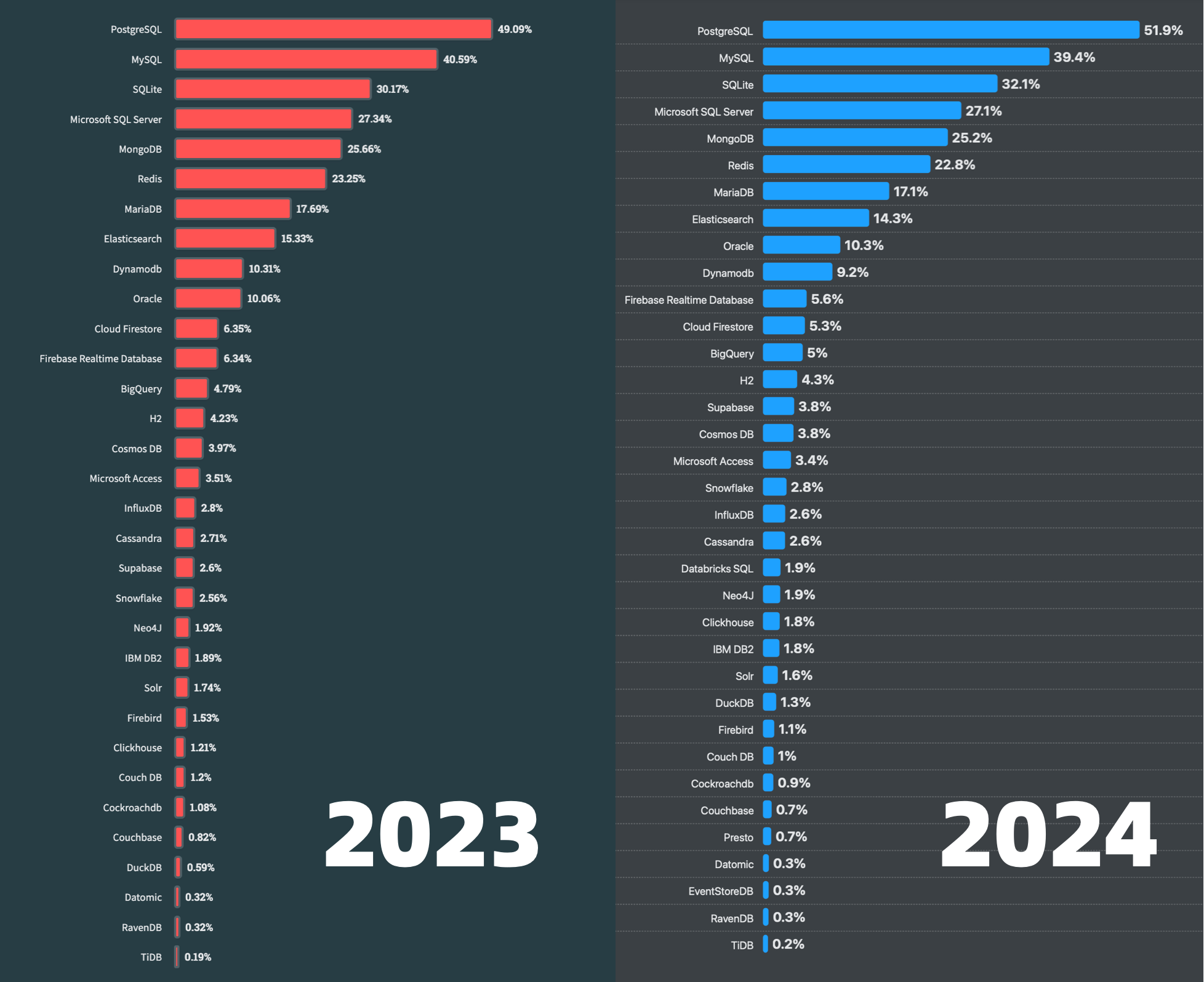

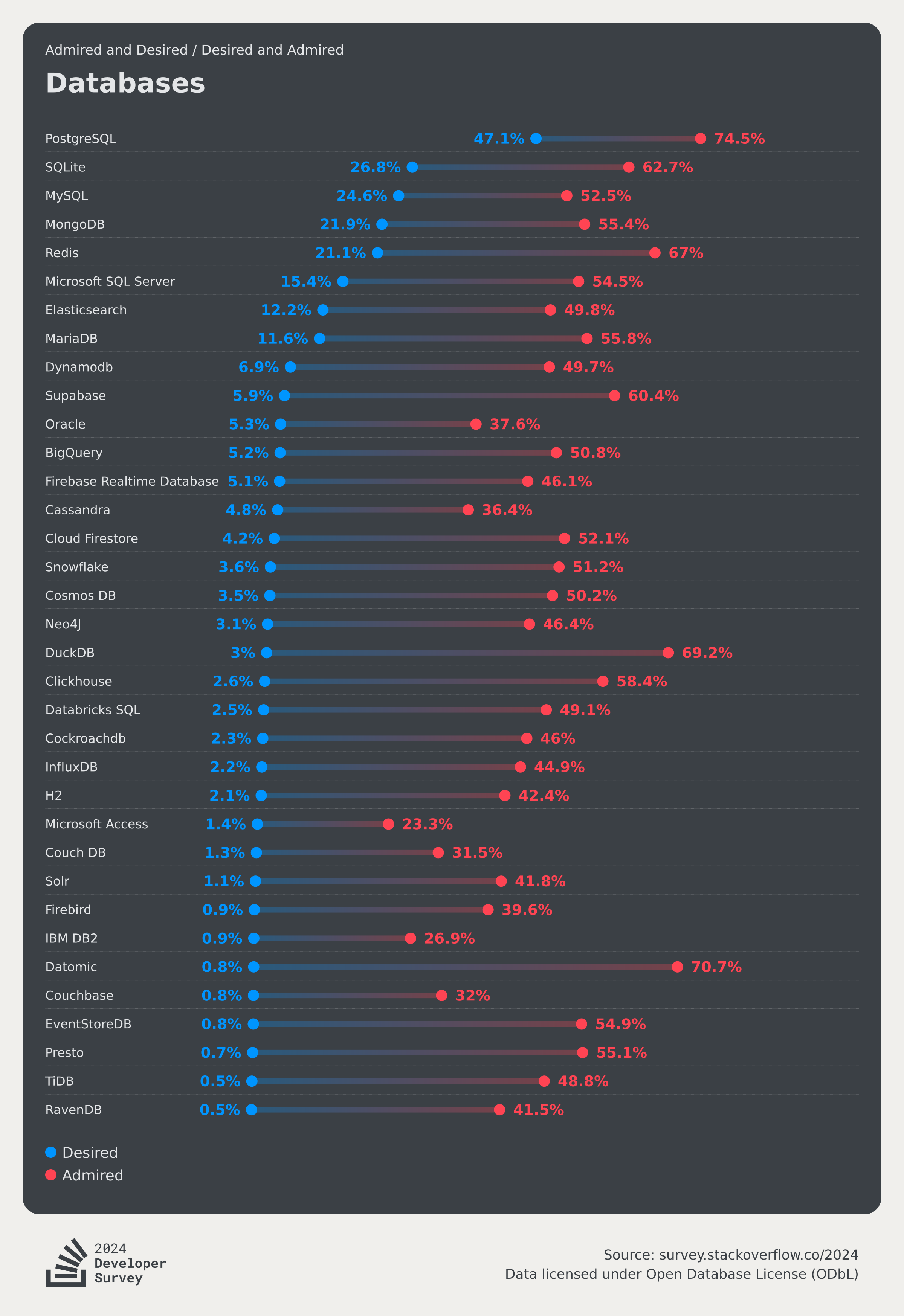

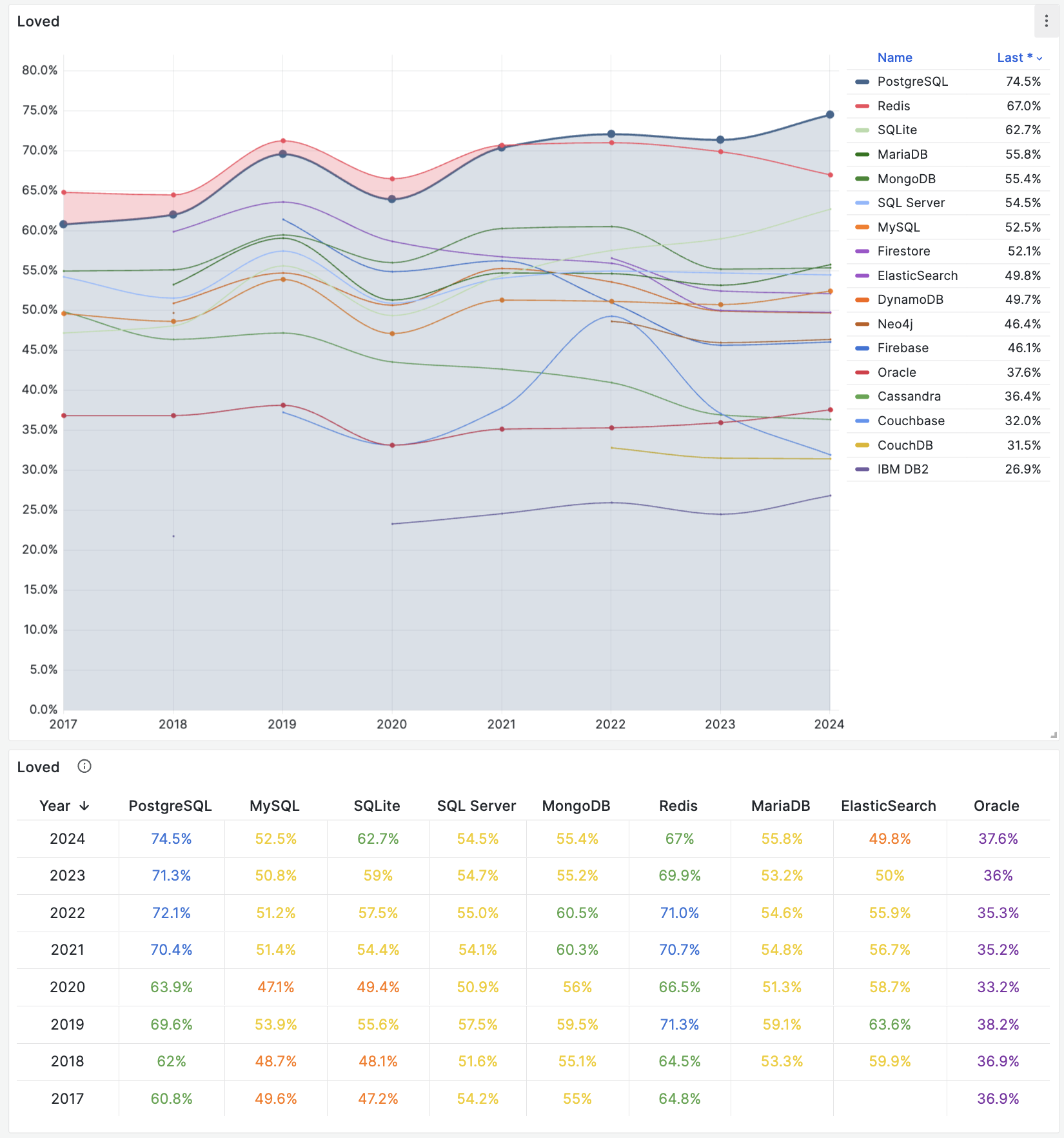

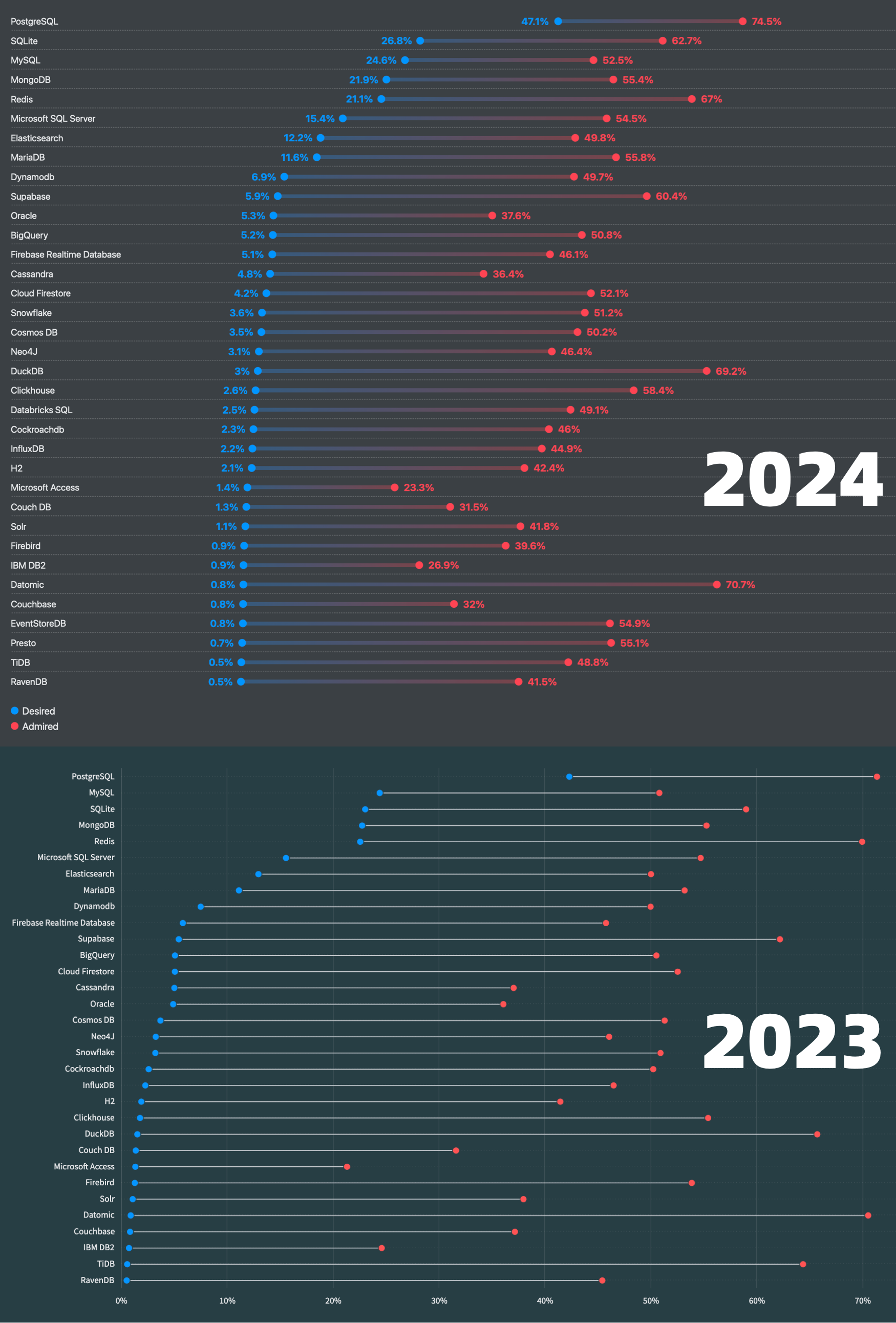

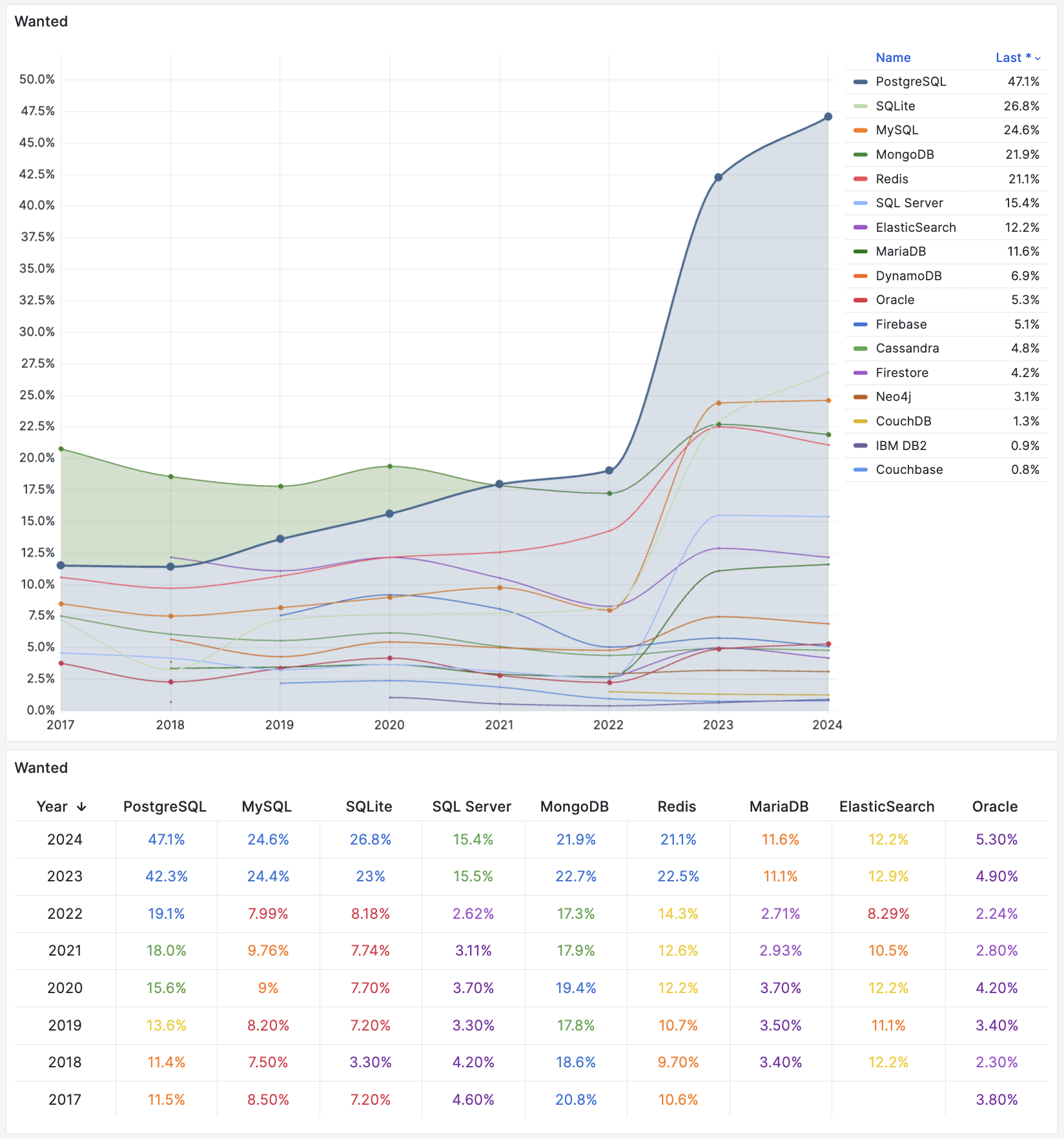

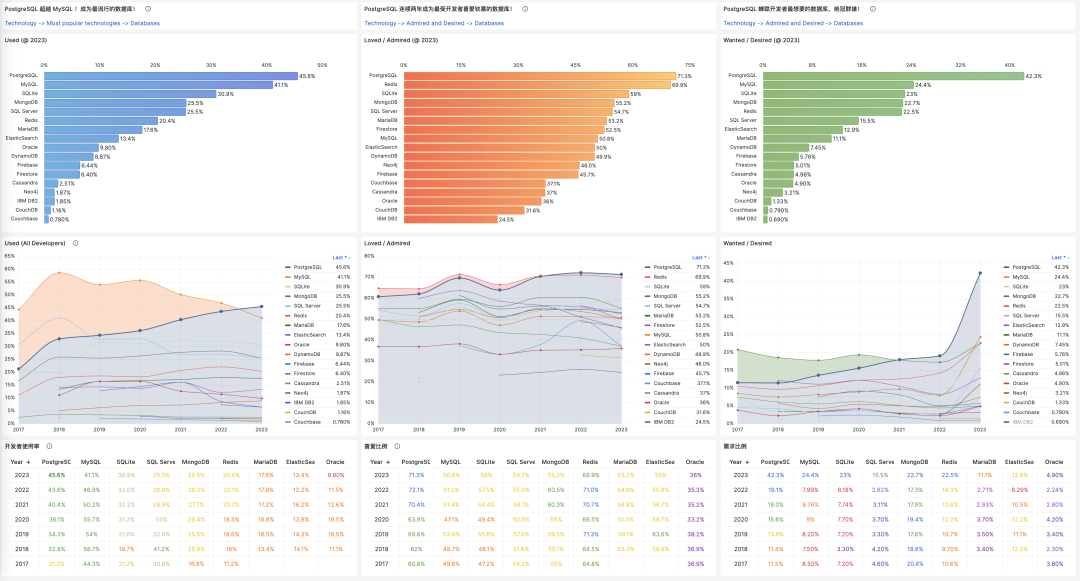

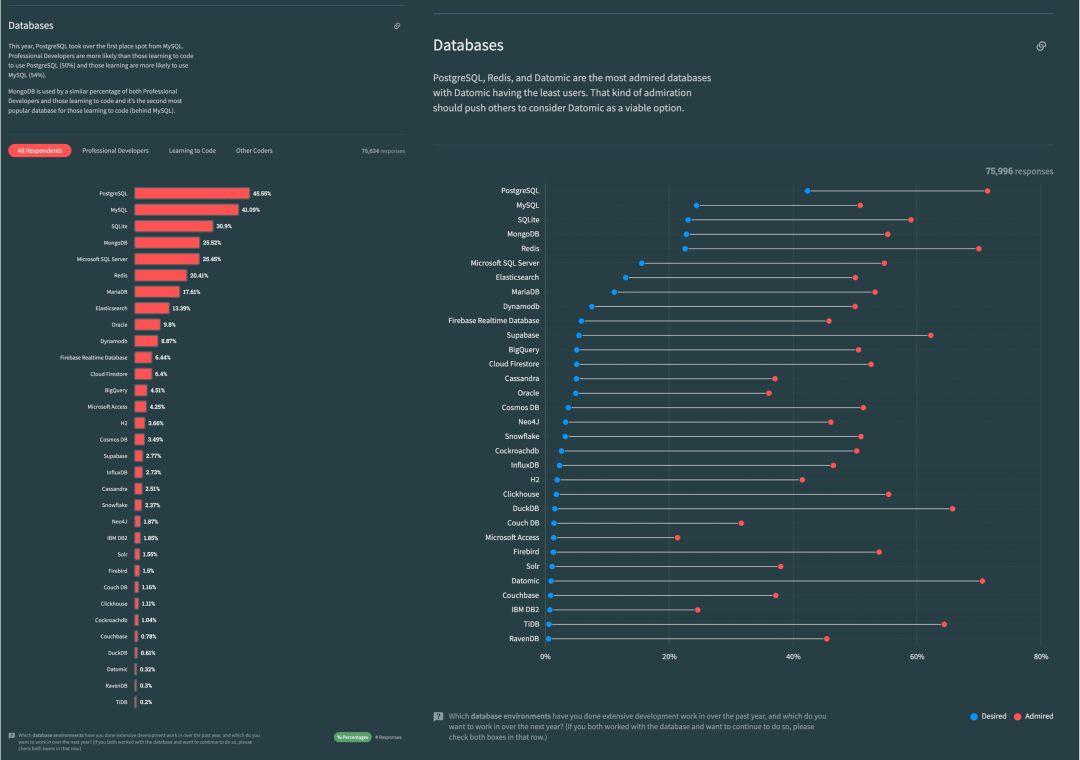

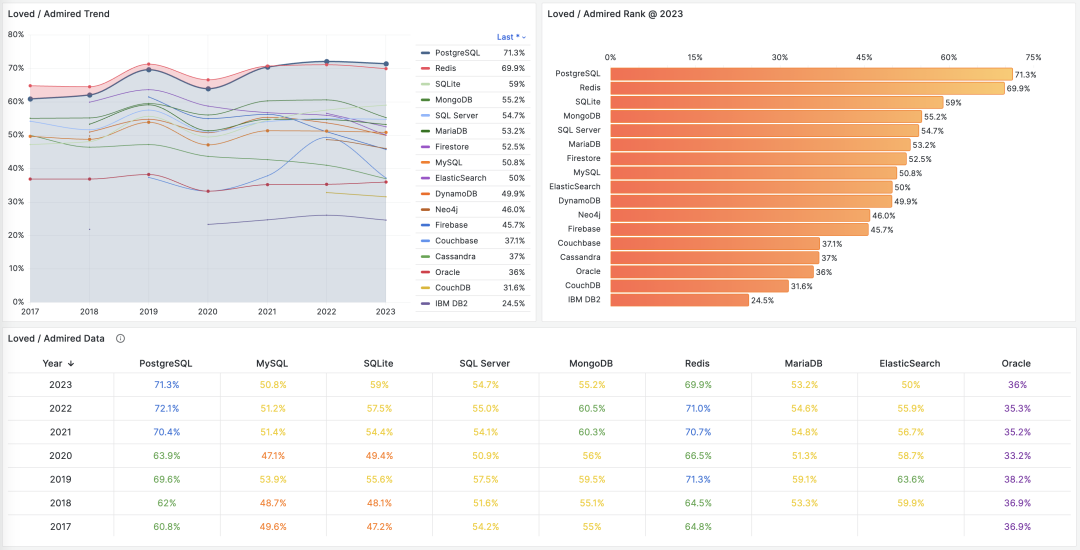

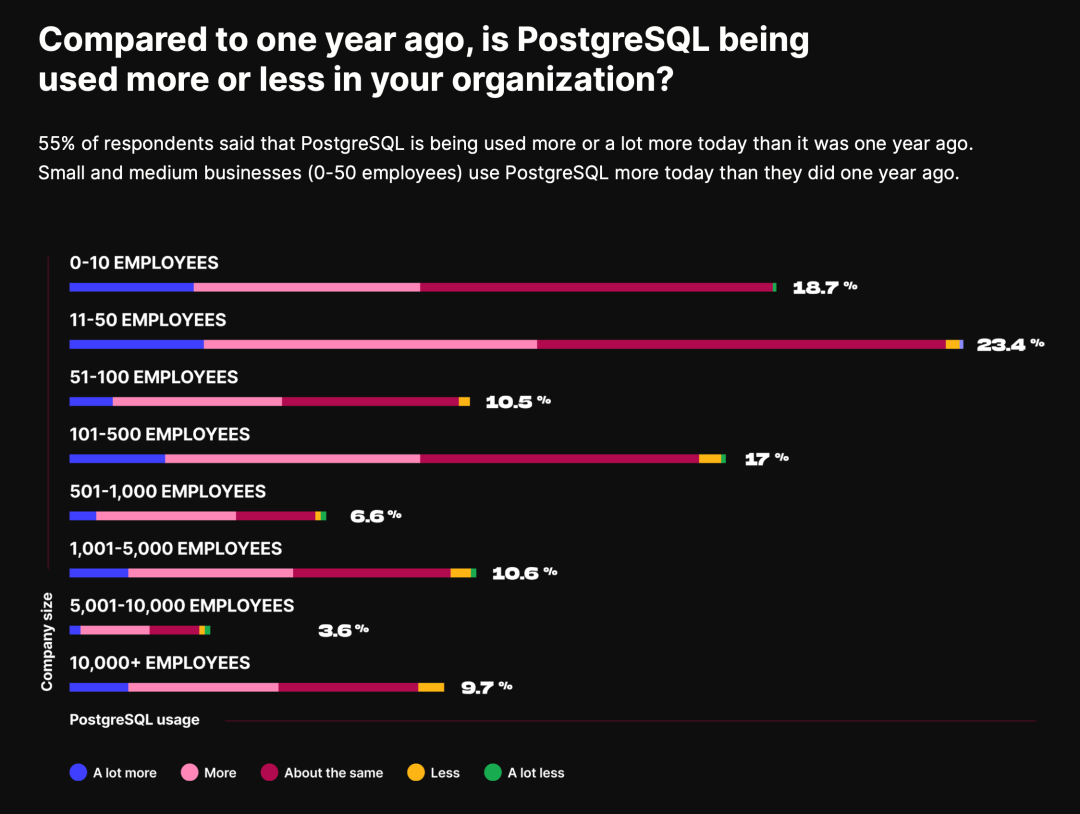

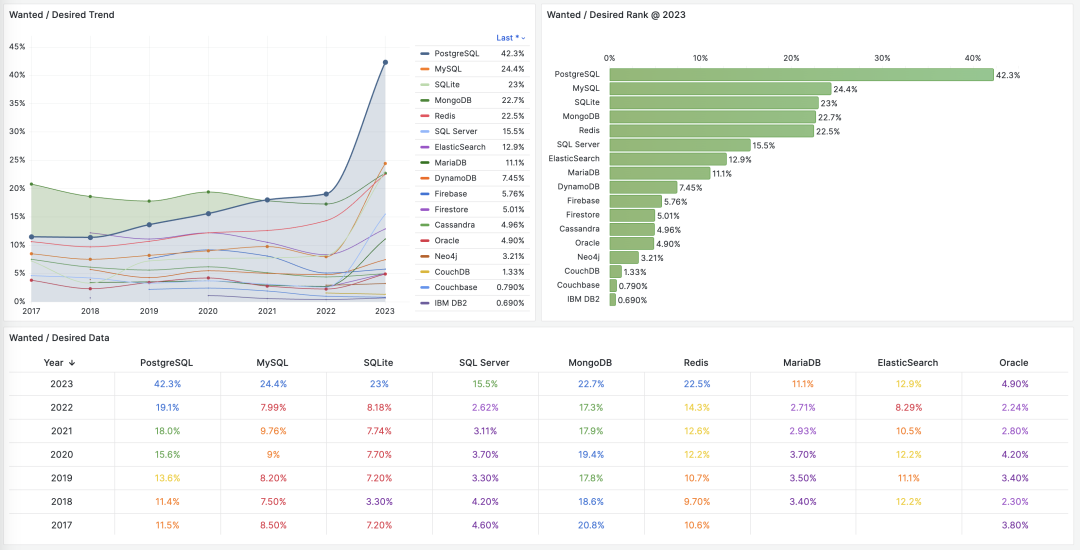

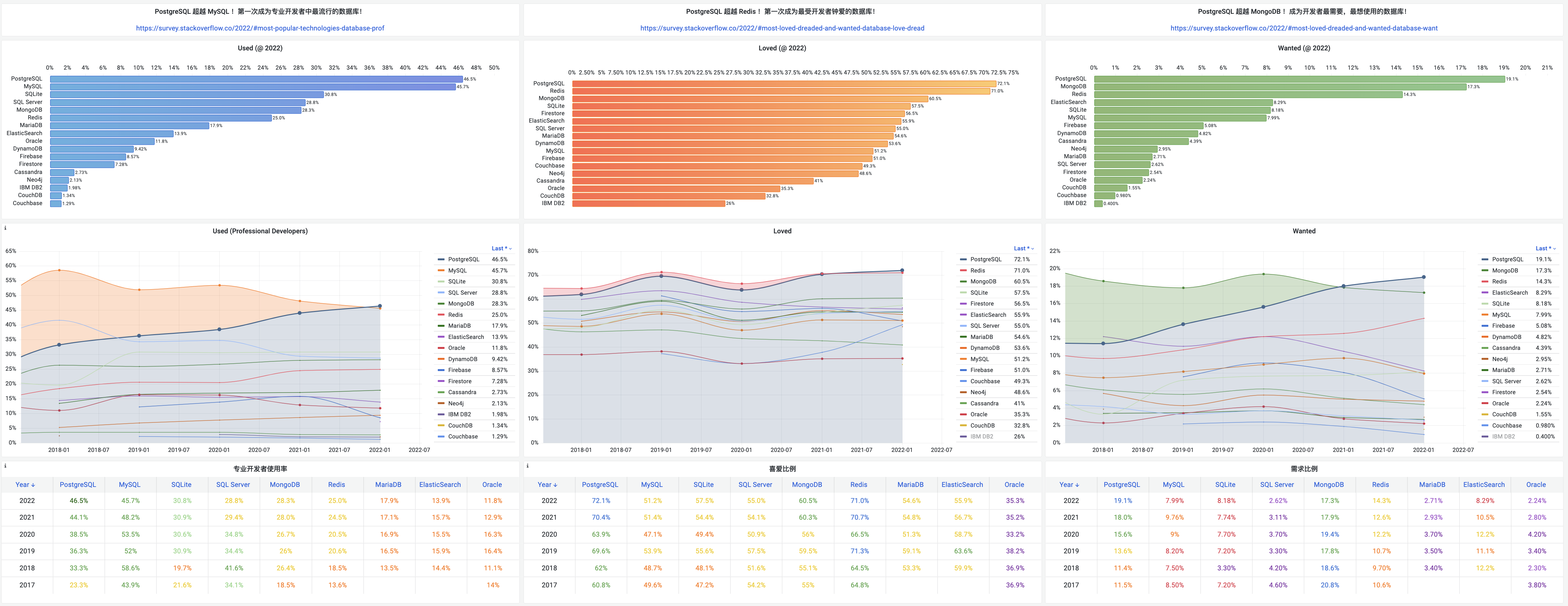

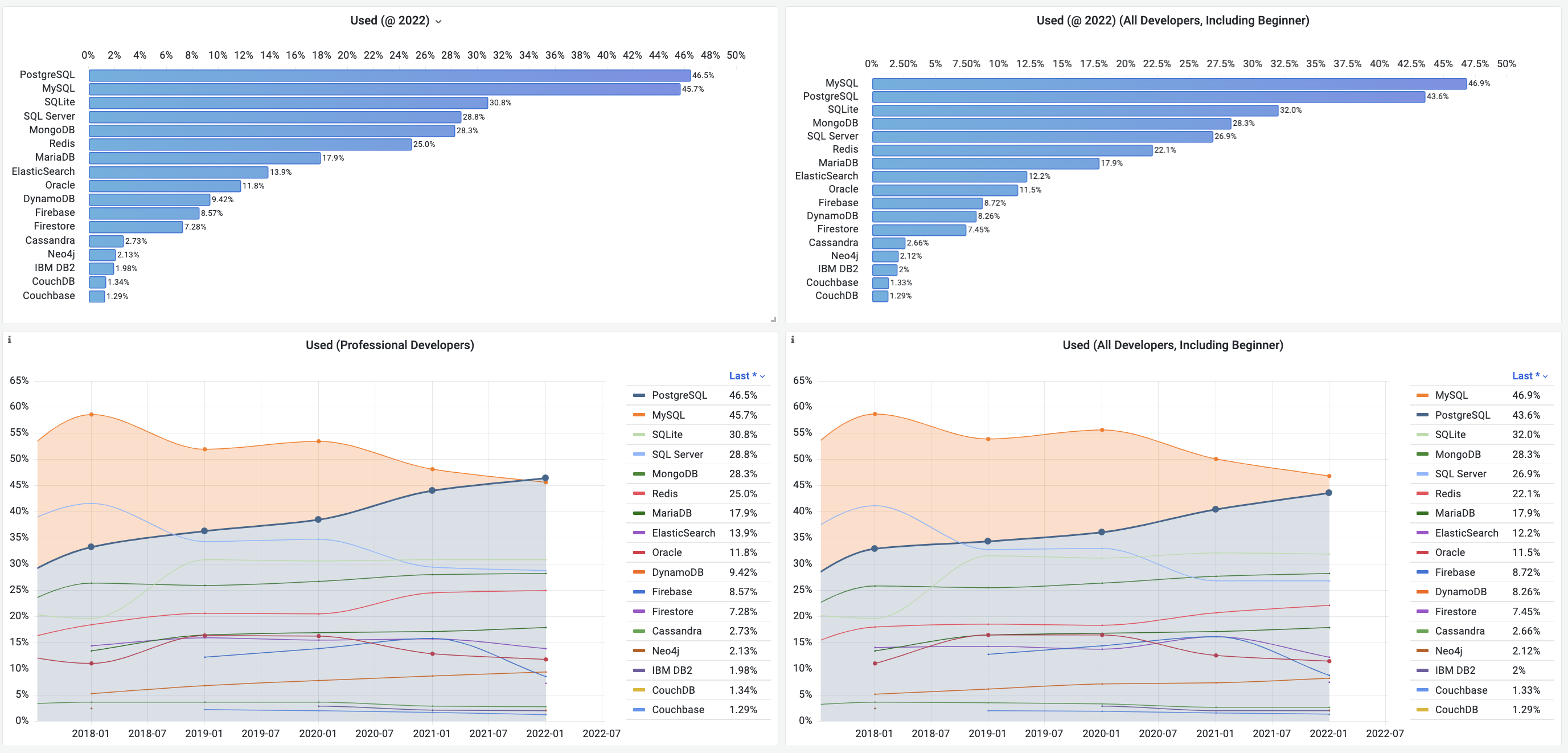

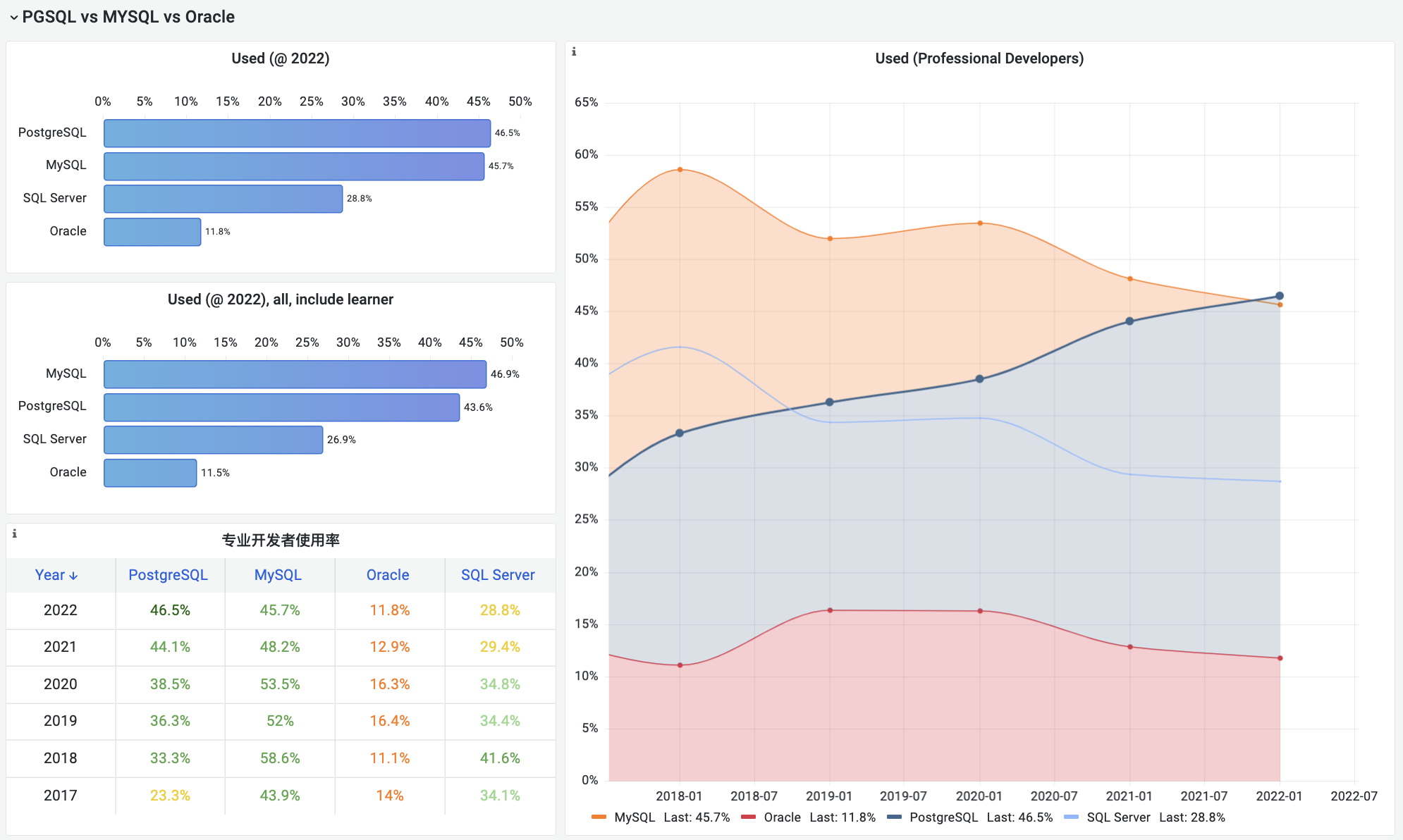

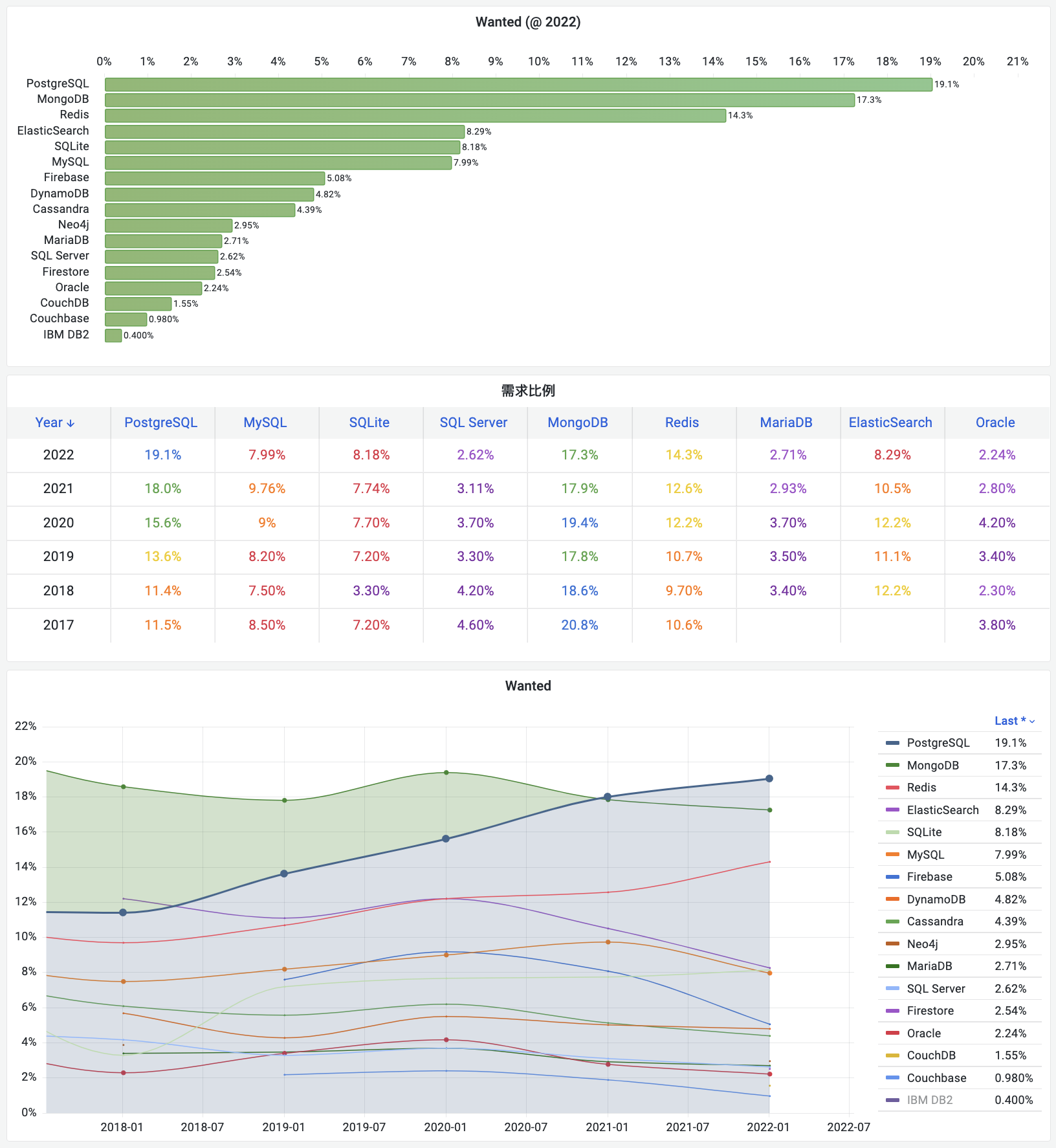

Unfortunately, at least according to the 2023 results of one of the world’s most authoritative developer surveys, the StackOverflow Annual Developer Survey, MySQL has been overtaken by PostgreSQL—the crown of the most popular database has been claimed by PostgreSQL.

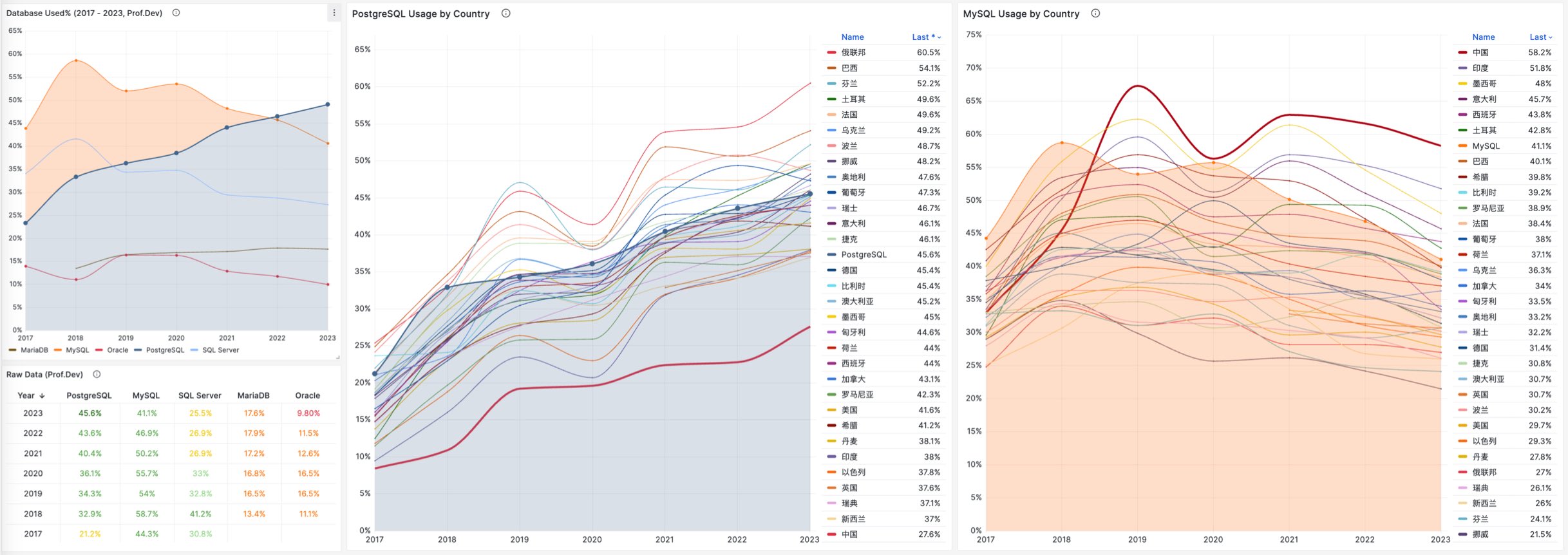

Especially notable, when examining the past seven years of survey data together, one can clearly see the trend of PostgreSQL becoming more popular as MySQL becomes less so (top left chart)—an obvious trend even under the same benchmarking standards.

This rise and fall trend is also true in China. However, claiming PostgreSQL is more popular than MySQL in China would indeed go against intuition and fact.

Breaking down StackOverflow’s professional developers by country, it’s evident that in major countries (31 countries with sample sizes > 600), China has the highest usage rate of MySQL—58.2%, while the usage rate of PG is the lowest at only 27.6%, nearly double the PG user base.

In stark contrast, in the Russian Federation, which faces international sanctions, the community-driven and non-corporately controlled PostgreSQL has become a savior—its PG usage rate tops the chart at 60.5%, double its MySQL usage rate of 27%.

In China, due to similar motivations for self-reliance in technology, PostgreSQL’s usage rate has also seen a significant increase—tripling over the last few years. The ratio of PG to MySQL users has rapidly evolved from 5:1 six or seven years ago to 3:1 three years ago, and now to 2:1, with expectations to soon match and surpass the global average.

After all, many national databases are built on PostgreSQL—if you’re in the government or enterprise tech industry, chances are you’re already using PostgreSQL.

Who Really Killed MySQL?

Who killed MySQL, was it PostgreSQL? Peter Zaitsev argues in “Did Oracle Ultimately Kill MySQL?” that Oracle’s inaction and misguided directives ultimately doomed MySQL. He further explains the real root cause in “Can Oracle Save MySQL?”:

MySQL’s intellectual property is owned by Oracle, and unlike PostgreSQL, which is “owned and managed by the community,” it lacks the broad base of independent company contributors that PostgreSQL enjoys. Neither MySQL nor its fork, MariaDB, are truly community-driven pure open-source projects like Linux, PostgreSQL, or Kubernetes, but are dominated by a single commercial entity.

It might be wiser to leverage a competitor’s code without contributing back—AWS and other cloud providers compete in the database arena using the MySQL kernel, yet offer no contributions in return. Consequently, as a competitor, Oracle also loses interest in properly managing MySQL, instead focusing solely on its MySQL HeatWave cloud version, just as AWS focuses solely on its RDS management and Aurora services. Cloud providers share the blame for the decline of the MySQL community.

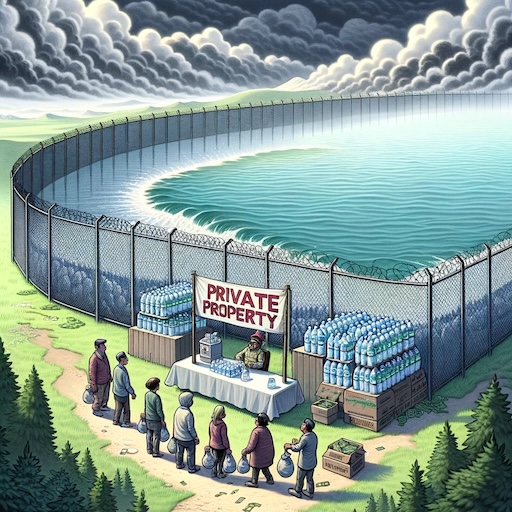

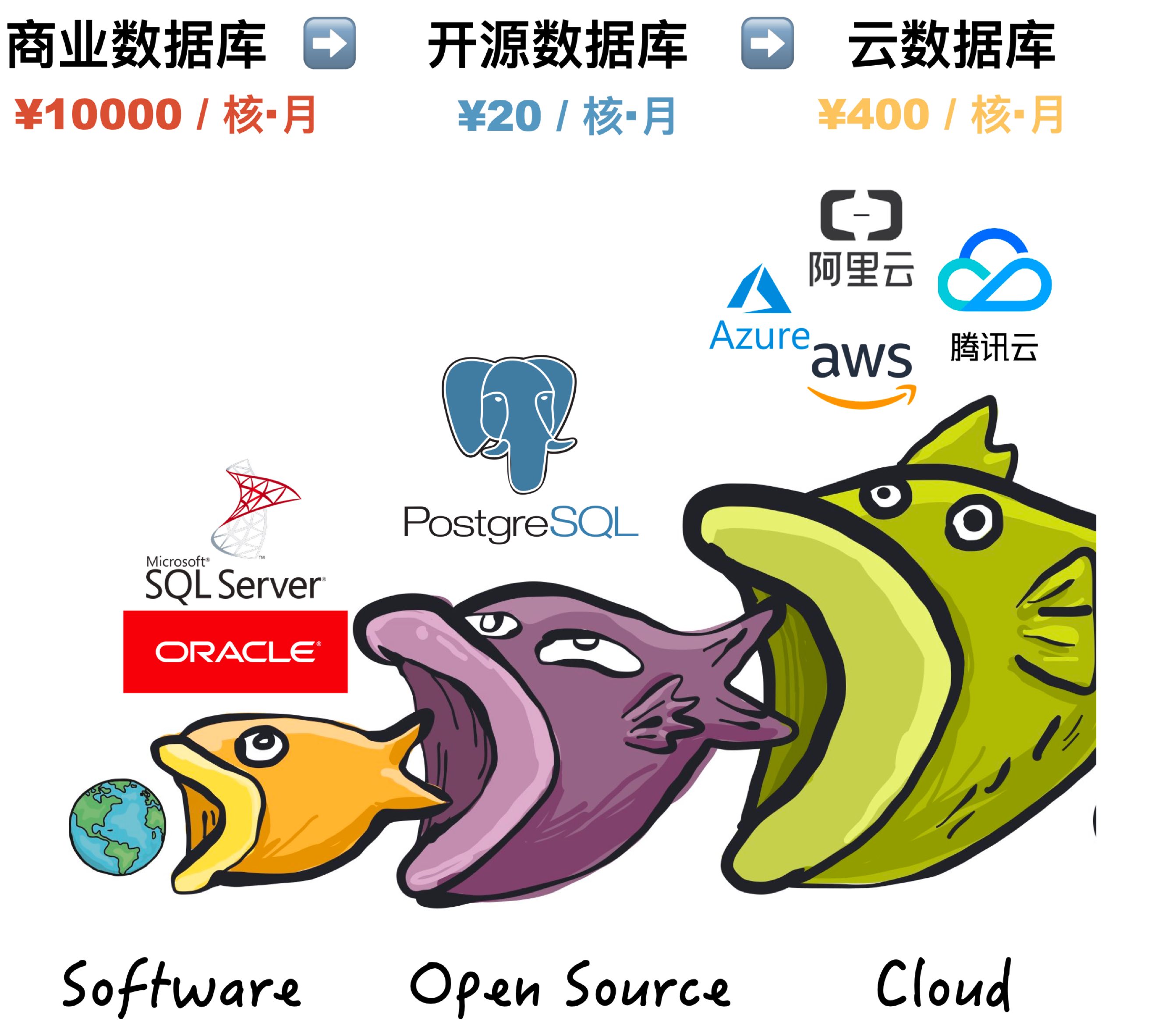

What’s gone is gone, but the future awaits. PostgreSQL should learn from the demise of MySQL—although the PostgreSQL community is very careful to avoid the dominance of any single entity, the ecosystem is indeed evolving towards a few cloud giants dominating. The cloud is devouring open source—cloud providers write the management software for open-source software, form pools of experts, and capture most of the lifecycle value of maintenance, but the largest costs—R&D—are borne by the entire open-source community. And truly valuable management/monitoring code is never given back to the open-source community—this phenomenon has been observed in MongoDB, ElasticSearch, Redis, and MySQL, and the PostgreSQL community should take heed.

Fortunately, the PG ecosystem always has enough resilient people and companies willing to stand up and maintain the balance of the ecosystem, resisting the hegemony of public cloud providers. For example, my own PostgreSQL distribution, Pigsty, aims to provide an out-of-the-box, local-first open-source cloud database RDS alternative, raising the baseline of community-built PostgreSQL database services to the level of cloud provider RDS PG. And my column series “Mudslide of Cloud Computing” aims to expose the information asymmetry behind cloud services, helping public cloud providers to operate more honorably—achieving notable success.

Although I am a staunch supporter of PostgreSQL, I agree with Peter Zaitsev’s view: “If MySQL completely dies, open-source relational databases would essentially be monopolized by PostgreSQL, and monopoly is not good as it leads to stagnation and reduced innovation. Having MySQL as a competitor is not a bad thing for PostgreSQL to reach its full potential.”

At least, MySQL can serve as a spur to motivate the PostgreSQL community to maintain cohesion and a sense of urgency, continuously improve its technical level, and continue to promote open, transparent, and fair community governance, thus driving the advancement of database technology.

MySQL had its days of glory and was once a benchmark of “open-source software,” but even the best shows must end. MySQL is dying—lagging updates, falling behind in features, degrading performance, quality issues, and a shrinking ecosystem are inevitable, beyond human control. Meanwhile, PostgreSQL, carrying the original spirit and vision of open-source software, will continue to forge ahead—it will continue on the path MySQL could not finish and write the chapters MySQL did not complete.

Reference

PostgreSQL 17 Beta1 发布!牙膏管挤爆了!

MySQL's Terrible ACID